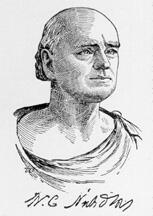

Wilson Cary Nicholas (January 31, 1761 – October 10, 1820) was an American politician and planter who held multiple state and federal offices, including service in both houses of the United States Congress and as the 19th Governor of Virginia. He was born in Williamsburg, in the Colony of Virginia, on January 31, 1761, the son of Robert Carter Nicholas Sr. and Ann Cary, and was a member of the First Families of Virginia. One of eleven children, ten of whom were born into the family and seven of whom reached adulthood, he belonged to an extensive political dynasty. His eldest brother George Nicholas (1754–1799) served in the Virginia legislature before moving to Kentucky; his brother John Nicholas (1756–1820) served as a Virginia legislator and U.S. Congressman before relocating to New York; and his youngest brother Philip Norborne Nicholas (1776–1849) served as Virginia’s attorney general from 1800 to 1819 and later as a state judge. Only his brother Lewis Nicholas (1766–1840) did not enter politics. His sisters also married into prominent families: Sarah Nicholas married John Hatley Norton of Winchester, and Elizabeth Carter Nicholas (1753–1810) married Edmund Jennings Randolph (1753–1813), who would precede Wilson Cary Nicholas as Governor of Virginia. Other siblings, including Mary (1759–1796), Judith (b. 1765), and Robert (b. 1768), died before reaching adulthood.

As was customary for his social class, Nicholas received a private education in Virginia before attending the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg. He studied law, probably under the guidance of his father and possibly with the noted legal scholar George Wythe. During the American Revolution, he served as a lieutenant in the Albemarle County Militia, an early indication of his engagement in public affairs. Nicholas was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1778 and, after the war, returned to Albemarle County, where he began to combine legal practice, plantation management, and an increasingly active political career. By 1794 he had settled his family at a plantation along the James River that he named “Mount Warren.” Like his father and many of his contemporaries, he farmed and operated his household using enslaved labor. In the 1787 Virginia tax census, he was recorded in Albemarle County as enslaving 39 adults and 23 children, and owning 22 horses, 49 cattle, and a four-wheeled phaeton.

Nicholas married Margaret Smith (1765–1849) of Baltimore, linking himself to another influential regional family. The couple had nine children. His brother George Nicholas married Margaret’s sister, Mary, making their brothers-in-law the prominent Baltimore figures Samuel Smith and Robert Smith. Among their descendants, Robert C. Nicholas, who moved to Louisiana and became a U.S. Senator, was particularly notable. Their daughter Jane Hollins Nicholas (1798–1871) married Thomas Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph (1792–1875), who later played a central role in managing the heavily encumbered estate of his grandfather. Several of Wilson Cary Nicholas’s children married into Baltimore families, including Mary Nicholas, who married John Patterson; Sarah Nicholas, who married J. Howard McHenry; and John Nicholas (b. 1800), who married Mary Jane Carr Hollins. Their children Wilson Nicholas and Margaret died unmarried, while Sidney Nicholas married Dabney Carr and Cary Ann Nicholas married John Spear Smith, all of whom had children.

Nicholas’s political career began in Virginia’s state legislature. Albemarle County voters elected him as one of their two members of the Virginia House of Delegates, where he served from 1784 to 1785 and again from 1788 to 1789, and then from 1794 to 1800 through a series of elections and re-elections. Both he and his brother George represented Albemarle County at the Virginia Ratifying Convention of 1788, where they supported adoption of the proposed federal Constitution. During the debates on June 6, 1788, Nicholas responded to Patrick Henry’s concerns about the difficulty of amending the new Constitution through an Article V convention, arguing that such conventions would be limited in scope, free from local distractions, and guided by established “general and fundamental regulations.” The convention ultimately voted to ratify the Constitution, despite opposition from many representatives of the Piedmont counties. Although Thomas Jefferson’s influence made the county a stronghold of Jeffersonian sentiment, the Nicholas family and their relative Edward Carter of Blenheim remained aligned with Federalist positions for some years.

Nicholas’s economic and agricultural activities paralleled his political ascent. At Mount Warren, he initially grew tobacco, the dominant crop in Albemarle County, but in the 1790s he was persuaded by Richmond merchant Robert Gamble to shift to wheat, in recognition of tobacco’s destructive impact on soil fertility and the rising market price of wheat. His efforts to develop his lands and control local commerce led to a long-running dispute with the Scott family over the location of tobacco and wheat warehouses on the James River. In 1789 he temporarily prevailed when the town of Warren was established on his property, but by 1817 the terminus of the Rockfish Gap Turnpike and the regional commercial focus had shifted to Scottsville. By the final federal census taken during his lifetime, Nicholas enslaved 57 people in Albemarle County, including 32 agricultural laborers, among them 9 girls and 8 boys under age 14, and 6 men and 6 women over age 45.

At the federal level, Nicholas’s congressional service spanned both chambers. Fellow legislators in the Virginia General Assembly elected him, as a Democratic-Republican, to the United States Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Senator Henry Tazewell. He served as one of Virginia’s U.S. Senators from December 5, 1799, until his resignation on May 22, 1804. After leaving the Senate, he became collector of the port of Norfolk, serving in that capacity from 1804 to 1807. Nicholas then re-entered electoral politics and won election as a Representative from Virginia in the United States Congress. A member of the Republican (Democratic-Republican) Party, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in the Tenth and Eleventh Congresses and served from March 4, 1807, until his resignation on November 27, 1809. During this period, which overlapped with the years 1799 to 1811 in which he was active in national politics, Nicholas contributed to the legislative process over three terms in office in Congress, participating in the democratic process and representing the interests of his Virginia constituents during a formative era in the early republic.

Nicholas’s highest state office came later, during the War of 1812 era. He was elected Governor of Virginia in 1814 and served as the Commonwealth’s 19th governor from 1814 until 1816, when he retired from that office in accordance with the state constitution’s prohibition on consecutive second terms. After his governorship, Nicholas remained engaged in financial and economic affairs. In 1816, following the chartering of the Second Bank of the United States under President James Madison, he became president of the Bank’s Richmond branch. By this time, his family ties to Thomas Jefferson had deepened through the marriage of his daughter Jane to Jefferson’s grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph, and the bank extended several loans to the aging former president, who was struggling with mounting expenses. Nicholas also engaged in extensive speculation in western lands, a practice that left him heavily indebted when the Panic of 1819 struck. Jefferson had endorsed two of Nicholas’s notes for $10,000 each, believing that Nicholas’s plantations were worth more than $350,000. After Nicholas’s death, however, his lands were valued at only about one-third of that estimate, and his estate proved insolvent, substantially worsening Jefferson’s already precarious financial condition.

Wilson Cary Nicholas died on October 10, 1820, at Tufton, the plantation home of his daughter Jane and her husband Thomas Jefferson Randolph, near Charlottesville, Virginia, on land associated with Jefferson’s Monticello. He was interred in the Jefferson family burying ground at Monticello. When Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, an inventory of his estate revealed that debts traceable to Nicholas’s insolvency far exceeded those Jefferson had personally incurred, contributing directly to the forced sale of Monticello’s furnishings and many of the enslaved people held there. These obligations were not fully extinguished by Jefferson’s descendants until 1878, following the death of Thomas Jefferson Randolph. Nicholas’s public legacy, however, was recognized during his lifetime and afterward: in 1818 the Virginia General Assembly named Nicholas County, in what is now West Virginia, in his honor, and a residence hall at the College of William & Mary also bears his name.

Congressional Record