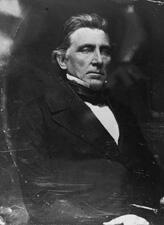

William McKendree Gwin (October 9, 1805 – September 3, 1885) was an American medical doctor, slaveholding planter, and Democratic politician who served in elected office in both Mississippi and California. In California he shared the distinction, along with John C. Frémont, of being one of the state’s first United States senators. A prominent figure in national politics before the Civil War, he was well known in California, Washington, D.C., and the Southern United States as a determined Confederate sympathizer. William McKendree Gwin served as a Senator from California in the United States Congress from 1841 to 1861, contributing to the legislative process during three terms in office and representing the interests of his constituents during a significant period in American history.

Gwin was born near Gallatin, Sumner County, Tennessee, on October 9, 1805. His father, Reverend James Gwin, was a pioneer Methodist minister who had served as a soldier on the frontier under General Andrew Jackson and as a chaplain at the Battle of New Orleans. The younger Gwin was named for Reverend William McKendree, America’s first native-born Methodist bishop and his father’s ecclesiastical superior. Raised in this frontier and religious milieu, Gwin pursued classical studies as a youth before entering higher education.

Gwin studied medicine at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, one of the leading institutions in the West at the time, and graduated from its medical department in 1828. As the son of a chaplain closely associated with Andrew Jackson, Gwin came into the orbit of national politics early; during Jackson’s second presidential term he served as a personal secretary to the president. After completing his medical training, he moved to Clinton, Mississippi, where he practiced medicine until 1833. That year he was appointed United States Marshal for Mississippi, a post he held for about a year. During his residence in Mississippi he acquired extensive plantation lands and enslaved laborers, becoming a substantial slaveholding planter as well as a physician.

Gwin entered elective office as a Democrat from Mississippi when he was chosen to represent the state in the Twenty-seventh Congress, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1841 to 1843. Although sometimes later remembered primarily as a senator, this House term marked his first service in the United States Congress. He declined renomination for a second term, citing financial embarrassment. With the accession of James K. Polk to the presidency in 1845, Gwin was appointed to superintend the construction of the new United States customhouse at New Orleans, Louisiana, further cementing his ties to the Democratic administration and to the expanding commercial life of the Gulf South.

Drawn by the opportunities of the gold rush and the rapid political development of the Pacific Coast, Gwin moved to California in 1849. He took part in the 1849 California Constitutional Convention, which framed the basic law under which the territory sought admission to the Union. Around this time he purchased property at Paloma, in Calaveras County, where a gold mine—known as the Gwin Mine—was established. The mine eventually yielded millions of dollars in gold, providing him with a considerable fortune and reinforcing his influence in the new state. In California he became the organizer and acknowledged leader of the “Chivalry” wing of the Democratic Party, a pro-Southern, pro-slavery faction that would dominate much of the state’s antebellum politics.

Before the formal admission of California as a state, Gwin was elected by the new legislature as a Democrat to the United States Senate. Upon California’s admission on September 9, 1850, he took his seat and served from September 10, 1850, to March 3, 1855, sharing the distinction with John C. Frémont of being one of California’s first U.S. senators. During the 32nd and 33rd Congresses he served as chairman of the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs, and he was a vigorous advocate of Pacific expansion and federal investment in the Far West. In 1851 he introduced a bill that became the Act of March 3, 1851, establishing a three-member Board of Land Commissioners, appointed by the President, to determine the validity of Spanish and Mexican land grants in California. Originally given three-year terms, the commissioners’ tenure was twice extended by Congress, resulting in a five-year period of operation for the Public Land Commission. Gwin also secured the establishment of a U.S. mint in California, a survey of the Pacific coast, and a navy yard and station on the West Coast, and he carried through the Senate a bill providing for a line of steamers between San Francisco, China, and Japan by way of the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii). By 1860 he was publicly advocating the purchase of Alaska from the Russian tsar.

Gwin’s prominence in California politics inevitably brought him into conflict with rivals. When California Governor John Bigler sought the ambassadorship to Chile and failed to obtain Gwin’s assistance, he turned instead to Gwin’s adversary, David C. Broderick. Bigler made Broderick chairman of the California Democratic Party, and the party soon split between Broderick’s faction and Gwin’s Chivalry wing. The rivalry produced a turbulent political climate marked by bribery, physical intimidation, and constant maneuvering. Gwin even fought a duel with Representative Joseph McCorkle, using rifles at thirty yards, after a dispute over alleged mismanagement of federal patronage; both men fired, but the only casualty was a donkey. Although Gwin’s faction remained powerful, the Broderick Democrats were strong enough to block his re-election to the Senate in 1855.

The rise of the nativist Know Nothing movement altered the political balance in California. When the Know Nothings exploited the division between the Gwin and Broderick factions, Broderick ultimately accepted Gwin’s candidacy as the best means of checking the new party’s advance. As a result, Gwin was returned to the United States Senate and served a second stretch from January 13, 1857, to March 3, 1861. During this term he also sat on the Senate Committee on Finance, further enhancing his influence over federal expenditures related to the Pacific Coast. He continued to press for measures that would tie California more closely to the rest of the nation and to the Pacific world, and he took the Japanese-born castaway Joseph Heco with him to Washington, D.C., introducing him to President James Buchanan as part of his broader interest in Pacific affairs. In 1858 Gwin challenged Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson to a duel during a heated dispute, but the matter was resolved by a senatorial arbitration committee, and no duel took place. Throughout his Senate career, which spanned three terms in Congress between 1841 and 1861 when his House and Senate service are combined, Gwin participated actively in the legislative process during a transformative era in American history.

As sectional tensions deepened on the eve of the Civil War, Gwin’s Southern sympathies became more pronounced. Although the new Republican Party made gains in several California cities, his Chivalry Democrats did well in the state elections of 1859. After Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency in 1860, Gwin helped organize secret, abortive discussions between Lincoln’s designated Secretary of State, William H. Seward, and certain Southern leaders in an effort to find a compromise that might avert the dissolution of the Union. Before open hostilities began, he toured the South and then returned to California, where his faction spoke publicly on behalf of Southern interests. At one point he entertained the possibility of a separate “Republic of the Pacific,” centered on California, seceding from the Union. However, when his party suffered severe reverses in the California elections of 1861, he recognized that there was little more he could do there to advance that cause.

Gwin left California for the East Coast, traveling on the same ship as Brigadier General Edwin Vose Sumner, commander of the Union Army’s Department of the Pacific. Sumner arranged for the arrest of Gwin and two other prominent secessionists, John Slidell—soon to be embroiled in the Trent Affair—and J. L. Brent. President Lincoln, however, intervened to secure their release, in part to avoid an international incident, as Gwin had influential friends in Panama. After his release, Gwin sent his wife and one of his daughters to Europe for safety while he returned to his Mississippi plantation. The plantation was destroyed during the war, and Gwin, accompanied by a daughter and a son, fled to Paris.

In 1864, while in Europe, Gwin sought to interest Emperor Napoleon III of France in a scheme to settle American slaveholders in the Mexican state of Sonora under French imperial auspices. Napoleon responded favorably, but his protégé, Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, rejected the plan, fearing that Gwin and his fellow Southerners might attempt to seize Sonora for themselves. After the collapse of the Confederacy, Gwin returned to the United States and surrendered himself to Major General Philip Sheridan in New Orleans. Sheridan initially granted his request for release so that he could rejoin his family, who had also returned from Europe, but this decision was countermanded by President Andrew Johnson, reflecting continued suspicion of Gwin’s Confederate sympathies.

In his final years, Gwin withdrew from national politics. He eventually retired to California, where he engaged in agricultural pursuits and managed what remained of his fortune and properties. Maintaining his connections on both coasts, he later spent time in the East and died in New York City on September 3, 1885. His body was returned to California, and he was interred in Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland in a large, pyramid-shaped mausoleum, a monument befitting a figure who had played a conspicuous and often controversial role in the political life of Mississippi, California, and the United States in the mid-nineteenth century.

Congressional Record