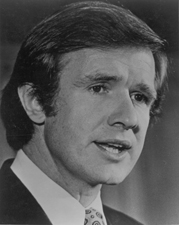

Thomas White Ferry (June 10, 1827 – October 13, 1896), commonly known as T. W. Ferry, was a Republican politician who represented Michigan in both the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate during a critical period in American history. Over the course of his national legislative career, he served five terms in Congress, including service in the House from 1865 to 1871 and in the Senate from 1871 to 1883. He rose to national prominence as president pro tempore of the Senate during the 44th and 45th Congresses and, during a vice-presidential vacancy between November 22, 1875, and March 4, 1877, was widely regarded and described at the time as the “Acting Vice President” of the United States.

Ferry was born in the old Mission House on Mackinac Island in the Territory of Michigan, then a small but important community that included a military garrison, the principal depot of John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company, and a Protestant mission. His father, the Rev. William Montague Ferry, was a Presbyterian pastor and missionary who also served as pastor of the island’s Protestant church, and his mother was Amanda White Ferry. The couple operated the mission school on Mackinac Island, where Thomas spent his earliest years. In 1834 the family moved to the frontier settlement of Grand Haven, Michigan, where he attended the public schools. As a young man he worked as a store clerk in Elgin, Illinois, from 1843 to 1845, before returning to Michigan. At the age of twenty-one he was elected clerk of Ottawa County, an early indication of his political promise. In addition to English, Ferry was fluent in Ottawa, Chippewa, and French, reflecting his upbringing in a multicultural Great Lakes environment.

Ferry’s state-level political career developed rapidly in the decade before the Civil War. He served as a member of the Michigan House of Representatives from 1850 to 1852 and as a member of the Michigan State Senate in 1856. On January 26, 1857, he joined with his father in platting the village of Ferrysburg, Michigan, which bore the family name and reflected their growing influence along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. Before the Civil War he became active in the emerging Republican Party, serving on the Republican State Central Committee for eight years. He was a delegate-at-large and one of the vice presidents of the national convention that nominated Abraham Lincoln for the presidency in 1860. After Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, Ferry was appointed by the United States Senate to a special committee that accompanied the late president’s body to Springfield, Illinois, for burial, underscoring his standing within the party and in national affairs.

Alongside his political work, Ferry was deeply involved in local education and business. In 1862 he became a director of the new Grand Haven Union High School and served as its superintendent for ten years, helping to shape secondary education in his community. He also entered the lumbering business with his brother, Edward Payson Ferry, participating in the booming West Michigan timber trade that underpinned much of the region’s economy. These activities, combined with his growing political responsibilities, made him one of the most prominent citizens of Grand Haven and the surrounding area.

Ferry’s national legislative career began during the closing months of the Civil War. A Republican, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives for the 39th, 40th, and 41st Congresses, serving from March 4, 1865, to March 3, 1871. He was re-elected to the House for the 42nd Congress in the general election of November 8, 1870, but before that term began the Michigan Legislature elected him to the United States Senate on January 18, 1871. Wilder D. Foster was chosen in a special election on April 4, 1871, to fill the vacancy Ferry left in the House. During his House service he took part in the major Reconstruction debates of the era. On April 2, 1868, he testified as a prosecution witness in the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson. One of his lasting procedural legacies in the House was his successful March 31, 1869, motion to adopt a rule requiring the Doorkeeper to clear the floor of visitors and non-privileged employees ten minutes before the start of a session, a rule later amended to fifteen minutes, which helped formalize decorum at the opening of daily proceedings.

In the Senate, Ferry served from March 4, 1871, to March 3, 1883, having been re-elected in 1877. His tenure coincided with the turbulent Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction years, including the economic crisis known as the Panic of 1873. During this period of severe deflation and financial distress, Ferry emerged as a leading Republican advocate of inflationary monetary policies. He introduced a measure that became known as the Ferry Bill, or “Inflation Bill,” in 1874, which proposed adding $64 million in greenbacks to the currency in circulation. The bill was popular among farmers and workingmen who hoped that inflation would ease debts and stimulate the economy, but it was strongly opposed by many Eastern bankers who feared it would weaken the dollar. The bill passed both the Senate and the House of Representatives, but President Ulysses S. Grant, a fellow Republican, vetoed it. An attempt to override the veto failed in the Senate by a vote of 34–30, making the Ferry Bill one of the relatively rare measures vetoed by a president of the same party as the bill’s sponsor. During his Senate career Ferry also served as chairman of the Committee on Rules and of the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads in the 46th and 47th Congresses, and he was the first person from Michigan to have served in both houses of the Michigan State Legislature and in both houses of the United States Congress.

Ferry’s most nationally visible role came through his service as president pro tempore of the Senate during the 44th and 45th Congresses. When Vice President Henry Wilson died on November 22, 1875, Ferry, as president pro tempore, became first in the line of presidential succession and remained so until March 3, 1877. Although the Constitution did not formally define the title, he was widely regarded and referred to, including by himself, as the acting vice president of the United States during this period. In that capacity he presided over two of the most consequential proceedings of the era: the 1876 impeachment trial of Secretary of War William W. Belknap and the meetings of the Electoral Commission created by Congress to resolve the disputed 1876 presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden. As president pro tempore, Ferry would have temporarily become acting president had the Electoral College vote not been certified by March 4, 1877; Congress ultimately certified Hayes as the winner on March 2. On July 4, 1876, during the nation’s centennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, President Grant designated Ferry, in his capacity as acting vice president, to officiate in his place. During the ceremony, Susan B. Anthony and four other women activists mounted the platform and presented Ferry with their “Declaration of Rights,” distributing copies to the crowd as they were escorted away, in a dramatic demonstration for woman suffrage that linked Ferry’s ceremonial role to a landmark moment in the women’s rights movement.

Ferry’s 1882–1883 bid for another Senate term drew intense national attention and became one of the most bitterly fought senatorial contests of the period. His political opponent, Representative Jay Hubbell, created a newspaper called the “Grand Army Journal,” a publication widely denounced as libelous and whose principal purpose was to defame Ferry and undermine his re-election prospects. Hubbell mailed the paper by the thousands, and although its charges were untrue, the stories damaged Ferry’s public image. Hubbell himself became widely despised in Michigan for fabricating attacks on what many considered the state’s most powerful politician, and he eventually withdrew from the race. At the same time, the Grand Rapids Times published a story alleging that Ferry had drunkenly insulted patrons at a Washington, D.C., hotel. The hotel proprietor, staff, and numerous colleagues from both parties refuted the account, insisting that Ferry did not drink and had been an exemplary guest during the twelve years he had resided there. Commentators such as the Chicago Inter-Ocean described the campaign against him as among the most “malignant and unscrupulous” ever waged against a public man and warned that, if Michigan replaced him, the state would lose seniority, committee influence, and relative power in Congress. Nevertheless, after enduring these personal attacks, Ferry recognized that his political career was nearing its end. He withdrew from the contest and threw his support behind his close friend Thomas W. Palmer, who was elected to succeed him in the Senate, to the disappointment of Ferry’s adversaries who had hoped to claim the seat themselves.

After leaving the Senate, Ferry’s life was marked by declining health and financial reversals. Following his political defeat, he traveled in Europe for three years to recover his mental and physical health. Returning to Grand Haven in 1886, he devoted himself to managing his business interests and repaying his debts. Over the years he had invested heavily in mining, lumber, and iron enterprises, including the Ottawa Iron Works. By the late nineteenth century, however, the West Michigan lumber industry had largely been exhausted, and political enemies targeted his iron business. These pressures, combined with broader economic changes, forced his companies into bankruptcy. Determined to meet his obligations, Ferry liquidated his business assets and paid more than $1,250,000 in personal debts, a sum equivalent to roughly $43,000,000 in 2025 dollars, transforming him from one of Michigan’s wealthier public men into a figure of financial ruin.

In his private life, Ferry never married, though he was reportedly engaged on several occasions. During his years in Washington he was considered one of the capital’s most eligible bachelors and was frequently described as wealthy, charismatic, handsome, and politically powerful. A Philadelphia newspaper dubbed him the “lady-killer” of his day, claiming that he “never fails to gather a harvest of hearts during their proper season.” Despite this reputation and his earlier prosperity, his final years were spent largely away from the national spotlight in Grand Haven, where he lived quietly after his business failures. He died there on October 13, 1896, at the age of sixty-nine. Ferry is interred in Lake Forest Cemetery in Grand Haven, in the Ferry family plot. His epitaph reads: “I have done what I could to extend our commerce over the world for the security of life and property along our seacoast, upon our great inland seas. T.W.F. The Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Friend. For 62 years a citizen of Grand Haven, Mich.” His family’s prominence is reflected in the careers of his brothers William Montague Ferry Jr., Noah Ferry, and Edward P. Ferry, and in the naming of Ferry Township in his honor.

Congressional Record