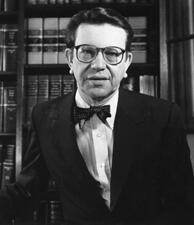

Sidney Breese (July 15, 1800 – June 27, 1878) was an American lawyer, soldier, author, and jurist who became an early Illinois pioneer and a prominent Democratic politician. He represented Illinois in the United States Senate from 1843 to 1849, served as Chief Justice of the Illinois Supreme Court and Speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives, and has often been called the “father of the Illinois Central Railroad” for his role in promoting that line. His public career unfolded during a formative period in Illinois and national history, and he played a significant role in the development of the state’s legal and transportation infrastructure.

Breese was born in Whitesboro, New York, in 1800, the second son of Arthur Breese (1770–1825) and his first wife, Catherine Livingston (1775–1808). Through his mother he was connected to the influential Livingston family of New York; his maternal grandfather was Henry Beekman Livingston, and he was also related to the Schuyler family. His elder brother, Samuel Livingston Breese, became a commodore in the United States Navy, and his sisters Sarah Breese Lansing and Elizabeth Breese Sands married into prominent New York families. He also had a half-sister, Sarah Ann Breese Walker. The painter and telegraph inventor Samuel Finley Breese Morse was a cousin, underscoring the family’s wide-ranging connections in early American public life.

Breese’s mother died when he was eight years old, and although his father remarried, much of his upbringing fell to the Rev. Jesse Townsend, under whose guidance he received a rigorous education. During this period he formed a close friendship with his slightly older cousin Elias Kent Kane, who would later become a leading Illinois politician and U.S. senator. Breese entered Hamilton College at the age of fourteen and later transferred to Union College in Schenectady, New York, in 1816. He graduated from Union in 1818, ranking third in a class of sixty-four and becoming a member of the New York Alpha chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. Influenced by Kane, who had moved to Illinois after graduating from Yale College in 1814, Breese decided to follow him west. After relocating to Illinois, he read law under Kane in 1820 and prepared for admission to the bar.

Illinois was admitted to the Union in 1818, and as the new state’s institutions were being organized, Kane became Illinois Secretary of State. He appointed Breese as his assistant, a position that allowed the young lawyer to participate directly in the establishment of the state government while continuing his legal studies. When the state capital moved in 1820 from flood-prone Kaskaskia on the Mississippi River to Vandalia on the National Road, Breese was responsible for transporting the State Department’s records by wagon, a task he successfully completed. He was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1821 and served as Assistant Secretary of State until the end of the legislative session that year, after which he returned to Kaskaskia to begin a private law practice. In 1821 he was also approached by the Post Office Department and accepted appointment as postmaster of Kaskaskia, earning commissions on postage stamp sales while building his legal career.

Breese’s early legal and public service career advanced rapidly. In 1822 he was appointed circuit attorney for the Third Judicial District of Illinois, a post he held until 1826, when he was removed by the new governor, Ninian Edwards. The following year, President John Quincy Adams appointed him United States Attorney for the State of Illinois. Although Adams was a National Republican (later associated with the Whigs), Breese, a Democrat, accepted the federal appointment and served until 1829, when President Andrew Jackson replaced him as part of a broader change in federal officeholders. Returning to private practice, Breese made a lasting contribution to Illinois legal history beginning in 1831, when he undertook the compilation and publication of the decisions of the Illinois Supreme Court. These volumes, known as the “Breese Reports,” were the first books published in Illinois and became foundational references for the state’s jurisprudence. During this period he also edited the Western Democrat under the pseudonym R. K. Fleming and in 1831 ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Congress on a platform advocating the transfer of all public lands to the individual states.

Breese’s public life also included military service. With the outbreak of the Black Hawk War in 1832, he volunteered as a private and was soon elected major. His battalion assembled at Beardstown in Cass County and marched to the Illinois River near Peru. At Camp Wilborn, after Lieutenant Colonel Theophilus W. Smith—who was also a justice of the Illinois Supreme Court—resigned his commission, Breese was elected to fill the vacancy and became lieutenant colonel. Under his command served future Civil War General Robert Anderson and future President Zachary Taylor, then a regular army officer, linking Breese’s frontier service to later national military leaders. After the war he returned to private practice and in 1833 served as lead counsel in the impeachment trial of Justice Smith before the Illinois House of Representatives. Working alongside future Illinois Governor Thomas Ford and future U.S. Senator Richard M. Young, Breese helped secure Smith’s acquittal when the legislature failed to reach the two-thirds vote required for conviction.

In addition to his courtroom work, Breese engaged in significant land and development matters during the 1830s. He platted an addition to the emerging town of Chicago and assisted early settler and trader Jean Baptiste Beaubien in asserting a land claim that included the soon-decommissioned Fort Dearborn. Although Breese and his colleagues prevailed before the Illinois Supreme Court, the United States Supreme Court reversed the decision in Wilcox v. Jackson (1837), despite the efforts of appellate counsel Francis Scott Key and Daniel Webster. In 1835, after the establishment of circuit courts in Illinois, the legislature appointed Breese a judge of the Second Judicial Circuit. In that capacity he presided over a notable 1838 case concerning whether Governor Joseph Duncan, a Whig, could remove Secretary of State Alexander Pope Field, a Democrat, and appoint another. In a highly charged partisan climate, Breese issued a narrowly legal opinion upholding the governor’s removal power. The Illinois Supreme Court later overturned his ruling, but in the ensuing political struggle, Democratic legislators expanded the supreme court from four to nine judges in the wake of the Panic of 1837, and Breese was elevated to one of the new seats, beginning his long tenure on the state’s highest court.

Breese’s prominence in Illinois law and politics led to his election as a United States Senator from Illinois. A member of the Democratic Party, he served one full term in the Senate from March 4, 1843, to March 3, 1849, representing his state during a period of rapid national expansion and intense debate over economic development and slavery. During his six years in the Senate, he participated in the legislative process on issues of public lands, internal improvements, and western development, and he worked to represent the interests of his Illinois constituents. His advocacy for a north–south railroad through Illinois, connecting the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, earned him the later reputation as the “father of the Illinois Central Railroad,” a project that would become critical to the state’s economic growth. After leaving the Senate in 1849, Breese returned to Illinois, where he continued his judicial and political career, including service as Speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives and ultimately as Chief Justice of the Illinois Supreme Court, further solidifying his influence on the state’s legal and political institutions.

In his personal life, Breese married Eliza Morrison (1808–1895) in 1823, the daughter of wealthy Illinois merchant William Morrison. The couple owned slaves and had a large family of fourteen children. Their children included daughters Eloise Philips McClurken (1824–1885) and Elizabeth Breese (1841–1845), and sons William Arthur Breese (1826–1838), Charles Broadhead Breese (1828–1844), (Samuel) Livingston Breese (1831–1899), who served in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War and attained the rank of commander by war’s end, Daniel L. Breese (1832–after 1860), who was a lieutenant in the U.S. Army in 1860, Sidney Samuel Breese (1835–1891), Edward Livingston Breese (1837–1838), William Morrison Breese (1838–after 1860), who worked as a land agent and lived at home as of 1860, James Buchanan Breese (1846–1887), who served as a second lieutenant in the Marine Guard during the Civil War, Elias Dennis Breese (1848–1851), and Alexander Breese (1850–1851). Several of his children died young, reflecting the high mortality of the era, while others continued the family’s tradition of military and public service. Sidney Breese remained a central figure in Illinois legal and political life until his death on June 27, 1878, leaving a legacy as a pioneering jurist, legislator, and advocate of internal improvements in the developing Midwest.

Congressional Record