Llewelyn Sherman Adams (January 8, 1899 – October 27, 1986) was an American businessman and Republican politician whose 18-year political career included service as a United States Representative from New Hampshire, governor of that state, and White House Chief of Staff to President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He was born in East Dover, Vermont, to grocer Clyde H. Adams and Winnie Marion Sherman, and spent his early years in New England. Raised in a family of modest means, he was educated in public schools in Providence, Rhode Island, and graduated from Hope High School there, experiences that rooted him in the civic and frugal values that later characterized his public life.

Adams pursued higher education at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, receiving his undergraduate degree in 1920. During World War I he briefly interrupted his studies for a six‑month stint in the United States Marine Corps, reflecting an early commitment to national service. At Dartmouth he helped found Cabin and Trail, the college’s influential hiking club, and was a member of the New Hampshire Alpha chapter of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity, establishing connections and interests—particularly in the New Hampshire outdoors—that would shape both his business endeavors and his later development of a ski resort. After college he entered the lumber business, first in Healdville, Vermont, in 1921, and then in a combined lumber and paper enterprise in Lincoln, New Hampshire; he was also involved in banking, building a reputation as a practical businessman. In 1923 he married Rachel Leona White; the couple had one son, Samuel, and three daughters, Jean, Sarah, and Marion.

Adams’s political career began in New Hampshire state politics as a Republican legislator. He served in the New Hampshire House of Representatives from 1941 to 1944 and rose quickly to prominence, becoming Speaker of the House in 1944. His clipped New Hampshire twang, emphasis on frugality, and insistence on balanced budgets made him an early exemplar of mid‑20th‑century Republican fiscal conservatism. These qualities, combined with his business background and legislative experience, positioned him for higher office and brought him to the attention of party leaders at both the state and national levels.

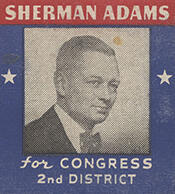

Sherman Adams served as a Representative from New Hampshire in the United States Congress from January 3, 1945, to January 3, 1947. A member of the Republican Party, he contributed to the legislative process during one term in office, participating in the democratic process and representing the interests of his New Hampshire constituents during a significant period in American history immediately following World War II. After his single term in the U.S. House of Representatives, he sought the Republican nomination for governor of New Hampshire in 1946 but lost to the incumbent, Charles M. Dale. Undeterred, Adams ran again and won the governorship in 1948, becoming the 67th governor of New Hampshire.

When Adams took office as governor in Concord in 1949, New Hampshire was suffering from a post‑war recession. He called for frugality and thrift in both personal and state expenditures, while also recognizing the needs of the state’s substantial retiree population. He advocated increased state aid for the aged and supported legislation to enable New Hampshire’s seniors to qualify for Federal Old Age and Survivors Insurance. In 1950 he formed a Reorganization Committee to recommend changes in state operations and urged the legislature to act on its proposals, seeking greater efficiency in government. During his tenure the New Hampshire Right to Work law, which had prevented people from being forced to join unions, was repealed. His prominence among state executives led to his service as chairman of the U.S. Conference of Governors from 1951 to 1952.

Adams’s national stature grew through his close association with Dwight D. Eisenhower. He took charge of Eisenhower’s campaign in the New Hampshire primary, securing all of the state’s delegates to the 1952 Republican National Convention. He then campaigned for Eisenhower across the country and served as Eisenhower’s floor leader at the convention in the contest against Senator Robert A. Taft, impressing Eisenhower with his hard work, mastery of detail, and political skill. Adams became Eisenhower’s campaign manager in the 1952 presidential race and was almost constantly at the candidate’s side. After Eisenhower’s victory, Adams was the obvious choice for White House Chief of Staff and became the first person to hold that title explicitly, as Eisenhower adapted a military-style staff system to the presidency.

As White House Chief of Staff from 1953 until 1958, Adams was one of the most powerful men in Washington. Under Eisenhower’s highly formalized staff structure, Adams controlled access to the President: with rare exceptions, anyone who wished to see Eisenhower required Adams’s prior approval, and, apart from Cabinet members and certain National Security Council advisers, all requests for access went through his office. This centralized authority alienated some traditional Republican leaders and made Adams a frequent target of Democratic criticism. He was known for his terse style and frequent use of a simple “No” on submissions, earning him the nickname “The Abominable No Man.” He handled much of the patronage and appointments that Eisenhower found tedious and was often responsible for dismissing officials when necessary. Generally aligned with the liberal wing of the Republican Party, he stood in opposition to the more conservative followers of Robert A. Taft and Barry Goldwater. Adams was a key broker in internal administration conflicts, including the decision to undercut Senator Joseph McCarthy after McCarthy began attacking the U.S. Army. His influence was such that contemporaries joked that it would be more consequential if Adams died and Eisenhower became President than if Eisenhower died and Vice President Richard Nixon became President, a reflection of the perception that Adams virtually controlled domestic policy and staff operations.

Adams’s political career ended abruptly in 1958 when a House subcommittee revealed that he had accepted an expensive vicuña overcoat and an oriental rug from Bernard Goldfine, a Boston textile manufacturer then under investigation for Federal Trade Commission violations and with business before the federal government. Goldfine was cited for contempt of Congress after refusing to answer questions about his relationship with Adams, and the scandal, first brought to public attention by investigative journalist Jack Anderson, forced Adams to resign as Chief of Staff. Vice President Nixon later stated that he had been assigned the difficult task of telling Adams he had to step down and expressed regret that Adams’s political career ended without any judicial findings against him. Contemporary reporting, including a Time magazine article on September 29, 1958, indicated that the formal responsibility for conveying Adams’s dismissal fell to Republican National Committee Chairman Meade Alcorn.

Following his resignation, Adams returned to Lincoln, New Hampshire, and turned his attention back to business and the outdoors that had long interested him. He began the development of Loon Mountain, which grew into one of the largest ski resorts in New England, thereby reshaping the local economy and further cementing his legacy in the state. He was active in hereditary and veterans’ organizations, including membership in the Society of Colonial Wars and the Sons of the American Revolution, and he was also associated with groups such as the American Legion and Freemasonry. In 1961 he published his memoir, First-Hand Report: The Story of the Eisenhower Administration, offering an insider’s account of the internal dynamics and policy debates of the Eisenhower years. Adams died on October 27, 1986, and his remains were interred at Riverside Cemetery in Lincoln, New Hampshire, closing the life of a figure who had moved from small-town New England commerce to the center of presidential power and back again to the mountains of his adopted state.

Congressional Record