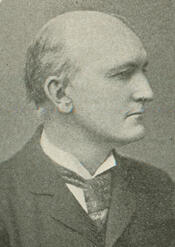

Samuel Walker McCall (February 28, 1851 – November 4, 1923) was an American Republican lawyer, politician, and writer from Massachusetts. He served for twenty years (1893–1913) as a member of the United States House of Representatives and was the 47th Governor of Massachusetts, holding three one-year terms from 1916 to 1919. A moderately progressive Republican, he sought to counteract the influence of money in politics and developed a reputation as an independent-minded reformer within his party. Over the course of ten consecutive terms in Congress, he represented Massachusetts as a member of the Republican Party and contributed actively to the legislative process during a significant period in American history.

McCall was born in East Providence Township, Pennsylvania, on February 28, 1851, the sixth of eleven children of Henry and Mary Ann (Elliott) McCall. When he was young, his family moved to an undeveloped frontier area of northern Illinois, where he spent much of his childhood. His father speculated in real estate and operated a stove factory, but the Panic of 1857 brought financial reverses that forced the closure of the business. McCall’s early education began at the Mount Carroll Seminary (now Shimer College) in Mount Carroll, Illinois, where he studied from 1864 to 1866, leaving when the institution closed its doors to male students. His parents then sent him east to New Hampton Academy in New Hampton, New Hampshire, on the recommendation of a neighbor, and he graduated from that academy in 1870.

Following his preparatory education, McCall attended Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. At Dartmouth he was a member of the Kappa Kappa Kappa fraternity and graduated Phi Beta Kappa near the top of his class. While still an undergraduate, he helped found and publish a student newspaper, the Anvil, which he and the other editors financed themselves. The Anvil was notable as one of the first student-run newspapers to comment extensively on national and state politics. During his college years he also demonstrated his classical scholarship; at the request of Dartmouth’s president he temporarily replaced a sick instructor, teaching Latin and Greek at an academy in Meriden, New Hampshire. These experiences foreshadowed his later career as a lawyer, legislator, and political writer.

After graduating from Dartmouth, McCall moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, where he studied law and gained admission to the Massachusetts bar. He subsequently opened a law practice in Boston with a Dartmouth classmate, a partnership he maintained for most of his professional life. In 1881 he married Ella Esther Thompson, whom he had met while attending New Hampton Academy, and the couple settled in Winchester, Massachusetts, where they raised five children. In addition to his legal work, McCall entered the world of journalism; in 1888 he and two partners purchased the Boston Daily Advertiser, and he served as its editor-in-chief for two years. His editorial work further developed his interest in public affairs and reform, and he became known as a thoughtful commentator on political issues.

McCall’s formal political career began in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, to which he was elected in 1887. He served three terms, in 1888, 1889, and 1892. Politically a reform-minded Mugwump—he had supported Democrat Grover Cleveland in the presidential election of 1884—McCall introduced legislation aimed at regulating “corrupt practices” by elected officials, seeking to reduce the influence of money and patronage in politics. Although his initial efforts met resistance, a version of his corrupt practices bill was finally enacted in 1892. He also supported legislation abolishing imprisonment for debt. Beyond the state legislature, he was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1888 and served as Massachusetts ballot commissioner in 1890 and 1891, roles that reinforced his interest in electoral integrity and political reform.

In 1892, McCall was elected as a Republican to the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts, beginning a congressional career that would last from March 4, 1893, to March 3, 1913. Over ten consecutive terms he generally won reelection by large margins and represented his constituents during a period marked by industrial expansion, the Spanish–American War, and the emergence of the United States as a world power. As in the state legislature, he introduced a federal corrupt practices act designed to curb the influence of money in national politics. In April 1898 he was one of only six representatives to vote against declaring war on Spain. In foreign policy he was a consistent anti-imperialist, arguing after the Spanish–American War that the Philippines should be granted independence rather than annexed by the United States. He opposed the Dingley Tariff, contending that its rates were excessively high, and he was one of the relatively few representatives to vote against the Hepburn Act, which expanded the Interstate Commerce Commission’s authority to regulate railroad rates. Although he often strayed from the Republican party line and was regarded as something of a maverick, his overall voting record remained generally conservative, and he introduced comparatively little new legislation beyond his core reform initiatives.

By 1912, McCall chose not to stand for reelection to the House of Representatives. Instead, he allowed his name to be put forward in the Massachusetts legislature’s selection of a United States senator to succeed Winthrop Murray Crane in early 1913. His principal opponent was Representative John W. Weeks, a more conservative Republican backed by the Crane-dominated state party apparatus. The contest was bitter and closely fought, reflecting the broader national split between progressive and conservative Republicans in the Progressive Era. Although McCall led in the party caucus balloting for the first three ballots, the legislature ultimately elected Weeks. McCall’s progressive leanings, while not sufficient to draw him into the Progressive Party, were nonetheless too liberal for many state party leaders, and this defeat marked one of two occasions on which he was denied a Senate seat.

In 1914, the Massachusetts Republican Party turned to McCall as its nominee for governor, hoping he could unify the party’s progressive and conservative wings. Running on a progressive platform against the popular Democratic incumbent, David I. Walsh, he was narrowly defeated, with Republican support divided by the presence of a Progressive Party candidate on the ballot. Renominated in 1915, the Republicans deliberately courted Progressive voters by endorsing the call for a state constitutional convention. In a rematch with Walsh, McCall was elected Governor of Massachusetts. He served three consecutive one-year terms from 1916 through 1918, with future President Calvin Coolidge as his lieutenant governor. In each of these elections Coolidge polled more votes than McCall, and contemporary observers, including the Boston Transcript, credited at least one of McCall’s victories in part to Coolidge’s popularity.

The Massachusetts Constitutional Convention of 1917–1918 was the central political event of McCall’s gubernatorial tenure. The convention proposed a series of reforms, most of which were subsequently adopted by the voters. Among the changes were the streamlining of state commissions and agencies and the introduction of initiative and referendum procedures into the state constitution. The convention also recommended changing elections for statewide offices from annual to biennial, a reform that took effect beginning in 1920. McCall advanced additional legislative reforms, including proposals to overhaul state insurance and public pension systems and to abolish capital punishment, but these measures were only partially adopted or failed in the legislature. His governorship was also defined by his leadership during World War I. Anticipating American entry into the conflict, he created the Massachusetts Public Safety Commission in early 1917, an emergency response and relief body that coordinated public agencies, charitable organizations, and major businesses. The commission, the first of its kind in the nation, played a major role in organizing wartime relief and was disbanded in 1918.

McCall’s most celebrated act as governor came in response to the Halifax Explosion of December 6, 1917, when a munitions ship detonated in Halifax, Nova Scotia, causing widespread devastation. Acting on fragmentary early reports, McCall quickly convened the Public Safety Commission and offered the stricken city unlimited assistance from Massachusetts. Under his direction, the state organized a major relief train, dispatched even before the full extent of the disaster was known, which was among the first to reach Halifax. Massachusetts representatives helped coordinate relief efforts on the ground, and temporary housing built in the city was named in McCall’s honor. The aid mission forged a lasting bond between Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, commemorated to this day by Nova Scotia’s annual gift of a Christmas tree to the city of Boston. In 1918, McCall declined to seek another term as governor and again sought a seat in the United States Senate. In a renewed contest with John W. Weeks for the Republican nomination, he withdrew after it became clear that the conservative Crane faction remained firmly behind Weeks. The general election was ultimately won by former Governor David I. Walsh in a Democratic upset. McCall refused to campaign for Weeks, a decision that contributed significantly to the end of his active political career. In 1920, President Woodrow Wilson nominated him to serve on the United States Tariff Commission, but the Republican-controlled Senate rejected the nomination.

Throughout his public life, McCall was deeply engaged in literary pursuits, writing for newspapers and magazines on political and historical topics. After leaving elective office, he continued to contribute to periodicals such as the Atlantic Monthly and devoted increasing attention to biographical writing. His published works include a biography of his mentor, former Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed, titled “The Life of Thomas Brackett Reed” (1914), and a biography of Pennsylvania congressman Thaddeus Stevens. At the time of his death he was working on a biography of Daniel Webster. His standing as a man of letters and public affairs was recognized by his election to the American Antiquarian Society in 1901.

Samuel Walker McCall died at his longtime home in Winchester, Massachusetts, on November 4, 1923. He was interred in Wildwood Cemetery in Winchester. His legacy in the town is commemorated by the naming of McCall Middle School in his honor. His influence on American public life extended into the next generation through his grandson, Tom McCall, who served as a two-term Republican Governor of Oregon from 1967 to 1975.

Congressional Record