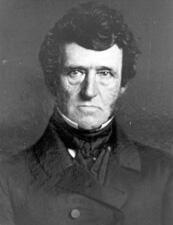

Robert Field Stockton (August 20, 1795 – October 7, 1866) was a United States Navy officer, Mexican–American War commander, and Democratic United States senator from New Jersey who played a prominent role in the capture of California and was an early advocate of a propeller-driven, steam-powered navy. Born at Morven, on Stockton Street in Princeton, New Jersey, he was a member of a distinguished political family. His father, Richard Stockton, served both as a United States senator and representative from New Jersey, and his grandfather, Judge Richard Stockton, was attorney general of New Jersey and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Of English descent, the Stockton family had been in what is now the United States since the early colonial period.

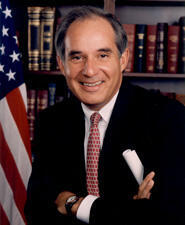

Stockton received his early education in New Jersey before entering naval service as a teenager. On March 4, 1823, he married Harriet Maria Potter in Charleston, South Carolina; the couple had ten children. Among them was John P. Stockton, who would later follow his father into public life and be elected as a United States senator from New Jersey. Stockton’s family connections and marriage further strengthened his ties to both national politics and the social elite of his era.

Stockton was appointed a midshipman in the United States Navy in September 1811, shortly after his sixteenth birthday, and saw active service at sea and ashore during the War of 1812. After the war he rose to the rank of lieutenant and served in the Mediterranean, the Caribbean, and off the coast of West Africa. He became one of the first U.S. naval officers to act directly against the transatlantic slave trade, capturing several slave ships. In December 1821, while commanding the USS Alligator along the Windward Coast of Africa, he joined Dr. Eli Ayers of the American Colonization Society in negotiating a treaty with local ruler King Peter that led to the founding of the colony that became the state of Liberia. Contemporary accounts describe Stockton using the threat of armed force—reportedly leveling a pistol at King Peter and arming Ayers to confront a mixed-race slave trader—to secure the land cession that enabled the establishment of the colony.

During the late 1820s and into the 1830s, Stockton largely withdrew from active naval duty and devoted himself to business and political affairs in New Jersey. He invested in transportation and industrial ventures and later owned and operated the Tellurium gold mine in Goochland and Fluvanna counties, Virginia, which he purchased in 1848 after its discovery in 1832. In 1835 he acquired a coastal estate in Monmouth County, New Jersey, known as “Sea Girt.” Decades later, when a group of land developers purchased the property in 1875, the name of Stockton’s estate influenced the naming of the borough of Sea Girt, New Jersey, upon its establishment in 1918. During this period his son John P. Stockton was born, extending the family’s political lineage into another generation.

Stockton returned to active naval service in 1838 with the rank of captain and was assigned to duty in European waters. Taking leave in 1840, he became deeply involved in national political questions. President John Tyler offered him the post of Secretary of the Navy in 1841, which Stockton declined, but he used his influence to secure support for the construction of an advanced steam warship armed with very heavy guns. This effort produced the USS Princeton, the first screw-propelled steamer in the United States Navy, designed by John Ericsson. Stockton commanded the Princeton upon its completion in 1843 and oversaw its armament with two large 225‑pounder wrought-iron guns, the “Peacemaker” and the “Oregon.” In February 1844 the Peacemaker exploded during a demonstration cruise on the Potomac River, killing two cabinet secretaries and several others. Although Stockton was closely associated with the design and promotion of the defective gun, his political standing helped ensure that a court of inquiry cleared him of responsibility for the disaster.

After the Peacemaker incident, Stockton remained in favor with the administration and was entrusted with sensitive diplomatic and military tasks. President James K. Polk sent him to Texas carrying the administration’s offer of annexation; Stockton sailed there in the Princeton and arrived at Galveston, then returned to Washington with observations that convinced him war with Mexico was imminent, a judgment he communicated directly to Polk. During the Mexican–American War, the Princeton proved highly valuable in the Gulf of Mexico, and Navy Department records later showed that she performed more service than the rest of the Gulf Squadron combined. On July 23, 1846, Stockton arrived at Monterey, California, and relieved the ailing Commodore John D. Sloat as commander of the Pacific Squadron. Sloat had already raised the United States flag at Monterey without resistance but had not pursued further operations ashore. With Stockton’s assumption of command, his flagship USS Congress and a combined force of frigates, a ship of the line, sloops, and storeships made him the senior military commander and military governor in Alta California.

As commander in California, Stockton became a central figure in the American conquest of the province. On August 11, 1846, he marched on Pueblo de Los Angeles to confront General José Castro’s forces; Castro withdrew toward Sonora, abandoning his artillery, and Stockton quickly consolidated American control. He dispatched frontiersman Kit Carson eastward as a courier to report his actions and the progress of the conquest to Washington. In December 1846 Stockton learned that Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny had arrived in California with a small force and was in grave danger at the Battle of San Pasqual, besieged by a larger Californio-Mexican cavalry force under Andrés Pico. Stockton personally organized and led a relief column that helped avert disaster for Kearny’s command. Subsequently, Stockton and Kearny’s combined forces secured San Diego and, in January 1847, won the engagements at the Battle of Rio San Gabriel and the Battle of La Mesa, retaking Los Angeles. Facing Stockton’s naval and land forces together with John C. Frémont’s California Battalion of roughly 200 men, the Californios sued for peace and agreed to the Treaty of Cahuenga, which ended organized fighting in Alta California. As senior military authority and military governor, Stockton authorized Frémont’s appointment as his successor as military governor and commander of the California Battalion militia. When Kearny later produced orders directing him to assume control of the temporary government, Stockton ultimately turned over authority to Kearny.

Stockton resigned from the Navy in May 1850 and returned to New Jersey to pursue business and political interests. In 1851 he was elected as a Democrat from New Jersey to the United States Senate, serving one term from 1851 to 1853. During his tenure he participated in the legislative process at a time of mounting sectional tension and sponsored a notable bill to abolish flogging as a punishment in the Navy, reflecting his continuing interest in naval reform and discipline. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented the interests of his New Jersey constituents in the Senate until his resignation on January 10, 1853, when he left Congress to become president of the Delaware and Raritan Canal Company. He held that position from 1853 until 1866, overseeing one of the key transportation links in the Mid-Atlantic region during a period of rapid economic and industrial growth.

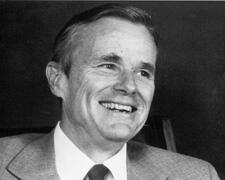

In his later years, Stockton remained engaged in public affairs. In early 1861 he served as a delegate to the Peace Conference held in Washington, D.C., an unsuccessful effort by leading political figures to resolve the secession crisis and avert civil war. Despite these efforts, the American Civil War began later that year. In 1863, during the Gettysburg Campaign, he was appointed to command the New Jersey militia when Confederate forces invaded Pennsylvania, reflecting the continued confidence of state authorities in his leadership. Stockton died in Princeton, New Jersey, on October 7, 1866, and was buried in Princeton Cemetery.

Stockton’s legacy has been widely commemorated in both the United States and abroad. Four United States Navy ships have borne the name USS Stockton in his honor. The cities of Stockton, California, and Stockton, Missouri; the borough of Stockton, New Jersey; Stockton Street in San Francisco; Stockton Street and the Garden Alameda neighborhood in San Jose; and Stockton Boulevard, the historic road linking Sacramento and Stockton, California, all carry his name. Fort Stockton in San Diego, now in ruins but active during the Mexican–American War, also commemorates his role in California. In Mariposa County, California, Stockton Creek was named for him in connection with a mine he owned during the Gold Rush, and in Liberia, Stockton Creek, a tidal channel between the Mesurado and Saint Paul rivers at Monrovia, likewise bears his name, recalling his early involvement in the founding of that nation.

Congressional Record