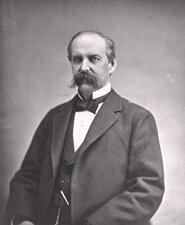

Nathaniel Peter Hill (February 18, 1832 – May 22, 1900) was a professor of chemistry at Brown University, a pioneering mining executive and metallurgical engineer, and a Republican politician who served as a United States Senator from Colorado from 1879 to 1885. Originally from the state of New York, he became a leading figure in the development of Colorado’s mining industry and in the political life of the territory and state, serving as mayor of Black Hawk and later as a U.S. Senator during a significant period in American history.

Hill was born on February 18, 1832, in Montgomery, Orange County, New York, at the Nathaniel Hill Brick House, which later became a museum. He was a descendant of Thomas Hale, one of the first settlers in Newbury, Massachusetts, who emigrated from England in 1635. As a young man, Hill took over operation of the family farm in Montgomery until he was twenty-one, while his eldest brother, James King, attended Yale University. During these years he pursued his education part-time at Montgomery Academy, demonstrating an early aptitude for scientific study that would shape his later career.

Hill left New York to attend Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, from which he graduated in 1856. Immediately upon graduation he joined the faculty at Brown, serving first as an instructor and later as a professor of chemistry from 1856 to 1864. He was among the first at Brown to introduce the concept of laboratory-based scientific instruction, adapting models he had observed or learned about from institutions in Europe. His growing reputation as a chemist and scientific investigator led to his recruitment by industrial interests seeking to develop mineral resources in the American West.

Hill’s scientific qualifications attracted the attention of Colonel William Reynolds, a cotton manufacturer, who invited him to search for mining areas in the West at a salary higher than his academic post. Enticed by this opportunity, Hill traveled to Colorado in the spring of 1864 to investigate mineral resources. He explored the region both alone and in the company of other scientists and entrepreneurs, but his initial efforts yielded little success. He returned to Providence, formally resigned his professorship at Brown, and resolved to devote the remainder of his life to the search for gold and the improvement of mining methods. Returning to the West, he purchased several gold mines and helped establish the Sterling Gold Mining Company and the Hill Gold Mining Company around Central City, Colorado. At that time, stamp milling was the preferred method of extraction, but as miners reached deeper sulfide-rich ores, recovery rates fell sharply, causing financial strain and unrest in the mining districts.

Confronted with the limitations of existing techniques, Hill turned to metallurgy to solve the problem of low yields from complex ores. In 1865 and 1866 he spent extended periods in Swansea, Wales, and Freiberg, Saxony, studying advanced smelting methods. There he learned and refined the copper matte, or Swansea, process, in which copper sulfide ore is mixed with gold- and silver-bearing ore so that the copper acts as a carrier for the precious metals during smelting. Returning to Colorado with a perfected smelting method, Hill settled permanently in Black Hawk. He worked with James E. Lyon, an entrepreneur he had met on his first Colorado trip who had erected the first substantial smelter in the area, but Hill’s improved processes soon surpassed earlier efforts. Drawing on his training as a chemist and his European experience, he founded the Boston & Colorado Smelting Company, which grew into a major enterprise encompassing multiple ventures beyond mining. Through the backing of prominent capitalists and collaboration with leading metallurgists, Hill oversaw large-scale smelting operations that significantly increased the profitability of Colorado’s mining industry and brought him considerable wealth and prominence.

Hill’s success in business led naturally to public service in Colorado’s territorial politics. He served as mayor of Black Hawk in 1871, where he was closely involved in the civic and economic affairs of the booming mining town. He was a member of the Colorado Territorial council in 1872 and 1873, participating in the legislative work that helped shape the territory’s transition toward statehood. In 1873 he moved to Denver, then emerging as the principal urban center of the region, and engaged in both smelting and real estate ventures. His growing influence in business and politics positioned him as a leading Republican voice in Colorado during the mid-1870s.

A member of the Republican Party, Hill was elected as a Republican to the United States Senate and served one term from March 4, 1879, to March 3, 1885, representing Colorado during a significant period in American history. He ran on a platform reflecting Republican ideals and support for free silver, advocating policies that, in his view, would promote economic development in the West. At the same time, he warned against the corruption of the American political system by special interests, including monopolies, and took an interest in issues such as communications infrastructure and monetary policy. During his Senate service he participated actively in the legislative process and represented the interests of his constituents. He served as chairman of the Committee on Mines and Mining in the Forty-seventh Congress, reflecting his technical expertise and the importance of mining to Colorado, and as chairman of the Committee on Post Office and Post Roads in the Forty-eighth Congress, where he was associated with proposals for a federal telegraph system. He was also involved in the work of the International Monetary Commission, engaging with broader questions of currency and international finance. His defeat by Henry M. Teller in 1885 ended his formal congressional career, but he remained an influential political figure in Colorado.

After leaving the Senate, Hill continued to be active in public affairs and business. He purchased The Denver Republican, a prominent newspaper, and used it as a platform to advocate for the causes he had championed in the Senate, including Republican policies, mining interests, and reform concerns related to monopolies and political corruption. He remained engaged in smelting, real estate, and other enterprises in Denver, maintaining his status as one of the state’s leading industrialists and civic leaders.

Hill’s personal life was closely tied to New England and to families with deep American roots. On July 26, 1860, he married Alice Hale of Providence, Rhode Island, who was born on January 19, 1840, and died on July 19, 1908. Alice’s father, Isaac Hale, was born in Newbury, Essex County, Massachusetts, on September 17, 1807, and her mother, Harriet Johnson, daughter of David Johnson and Lucy Towne, was born in Newbury, Vermont, on July 29, 1814. David Johnson was a son of Colonel Thomas Johnson, who distinguished himself during the Revolutionary War. Nathaniel and Alice Hill had three children: Crawford Hill, who later married the noted Denver social leader Louise Sneed Hill; Isabel; and Gertrude. Nathaniel Peter Hill died in Denver, Colorado, on May 22, 1900, from a stomach disease, and was interred in Fairmount Cemetery, leaving a legacy as a scientist, industrial innovator, and public servant who helped shape the economic and political development of Colorado.

Congressional Record