Lewis Charles Levin (November 10, 1808 – March 14, 1860) was an American politician, newspaper editor, and anti-Catholic social activist who emerged as one of the most prominent nativist leaders of the mid-nineteenth century. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, he was of Jewish descent and later became known as the second person of Jewish ancestry elected to the United States Congress, following David Levy Yulee. Before settling in Pennsylvania, Levin led a peripatetic professional life, practicing law successively in South Carolina, Maryland, Louisiana, and Kentucky. Contemporary observers described him as a “brilliant adventurer” and an exceptionally gifted public speaker whose oratorical talents would later fuel both his temperance advocacy and his nativist political career.

Levin’s formal education and early legal training are not extensively documented, but by the late 1830s he had shifted his focus from law to public lecturing and journalism. By 1838 he was in Philadelphia, where he began to gain public attention as a lecturer on the evils of alcohol. His dynamic speaking style quickly made him a popular figure on the temperance circuit. He founded and edited a journal titled the Temperance Advocate and Literary Repository, using it as a platform to promote abstinence from alcohol and to argue for stricter regulation of taverns. In 1842 he staged an immense public “bonfire of booze” in Philadelphia, a highly publicized event designed to dramatize his campaign against taverns and to advocate for local control of liquor licensing. His work in the temperance movement honed his skills as a mass agitator and organizer, preparing him for a broader political role.

Levin’s transition from temperance reformer to nativist political leader occurred in the early 1840s, as he increasingly focused on what he portrayed as the threat of Catholic political influence in the United States. He became editor of The Daily Sun in Philadelphia, which he used as a vehicle to attack Catholicism and to promote a nativist version of “Americanism” espoused by some northern Protestants at the expense of Catholics. A key flashpoint was an 1843 public school ruling that permitted Catholic children to be excused from Bible-reading classes because the Protestant King James Version of the Bible was being used. Levin seized on this controversy, arguing that such accommodations signaled undue Catholic influence in public institutions. He emerged as the leader and chief spokesman for a new political organization calling itself the American Republican Party, later known as the Native American Party, which was a precursor to the broader American (Know-Nothing) Party movement he helped found in 1842.

In his writings and speeches, Levin railed not only against domestic Catholic influence but also against international Catholic and Irish political movements. He attacked Daniel O’Connell, the Irish politician, and O’Connell’s Repeal Association, which sought to overturn the 1800 Act of Union and restore Irish legislative independence. Levin alleged that the Repeal Clubs O’Connell encouraged Irish immigrants to form in the United States were in fact beachheads for Catholic power and instruments of an eventual papal takeover of the country. His rhetoric, which combined religious prejudice, anti-immigrant sentiment, and conspiracy theories, was emblematic of the nativist Americanism ideology he championed. Although he was widely recognized as a dynamic and graceful orator, “charming in rhetoric and utterly reckless in assertion,” many of his speeches spread xenophobia and inflamed sectarian tensions.

Levin played a leading role in the Philadelphia nativist riots of 1844, some of the most violent episodes of religious and ethnic conflict in antebellum America. On May 3, 1844, nativists attempted to give a speech in the Irish-Catholic neighborhood of the Third Ward in Kensington, Philadelphia. Local residents drove the protesters out, but on May 6 Levin returned with an estimated 3,000 supporters. The ensuing clashes left several people dead and injured, and hundreds homeless as rioters burned much of the neighborhood. The violence culminated in the destruction by fire of two Catholic churches, St. Michael and St. Augustine, along with many Irish American homes. New riots broke out in Southwark in July 1844 when a mob threatened to destroy St. Philip Neri Catholic Church. On that occasion Levin used his influence to prevent the mob from burning the church, but the broader wave of violence had already resulted in the killing of over 20 Irish Americans, the burning of many of their homes, and the destruction of three Catholic churches associated with their community. Following the July riots, Levin and his colleague Samuel R. Kramer, publisher of the Native American, were arrested on charges of “exciting to riot and treason” for allegedly inciting locals to invade and burn several Catholic churches and a convent, though the case never went to trial.

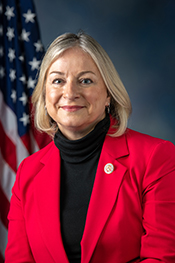

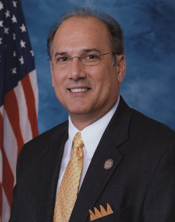

Levin’s prominence in the nativist movement propelled him into national politics. Running under the banner of the American Republican and Native American parties, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania’s 1st congressional district and served three consecutive terms from March 4, 1845, to March 3, 1851. He was elected by a substantial majority and re-elected in 1846 and 1848, representing the city of Philadelphia. In Congress he continued to advocate nativist positions, including restrictions on immigration and longer naturalization periods, and he remained a vocal critic of Catholic influence in public life. His tenure coincided with the broader rise of nativist sentiment in the 1840s, and he became one of the best-known congressional spokesmen for that cause. As a Jewish member of Congress who actively promoted discrimination against another religious minority, he later drew critical attention from historians of American religious freedom; writer Steven Waldman, for example, cited Levin as “proving that being part of a persecuted group does not necessarily bring sensitivity to the plight of other religious minorities.”

After leaving Congress in 1851, Levin’s political influence waned along with the fortunes of the early nativist parties, even as anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment reemerged in the later Know-Nothing movement. He continued to be remembered in Pennsylvania political circles as one of the most effective stump speakers of his era, with contemporaries remarking that few in either party surpassed him on the hustings. However, his later years were marked by serious mental health problems. Newspapers reported that he was committed to an asylum on more than one occasion. In June 1859, after visiting a brother in Columbia, South Carolina, he reportedly became “dangerous and unmanageable” while traveling by train to Richmond, Virginia. Friends and railway workers subdued him and confined him in the mail car until he could be returned to Philadelphia. The precise nature of his illness was unclear, though at least one newspaper speculated that “his insanity is supposed to have been brought about by an immoderate use of opium.”

Towards the end of his life Levin was deemed insane and committed to the Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane. He died there in Philadelphia on March 14, 1860, with “insanity” listed as the cause of death. He was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia. Levin’s career left a complex legacy: he was a pioneering Jewish member of Congress and a powerful orator, yet he was also a central figure in some of the most virulent episodes of anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant agitation in nineteenth-century America.

Congressional Record