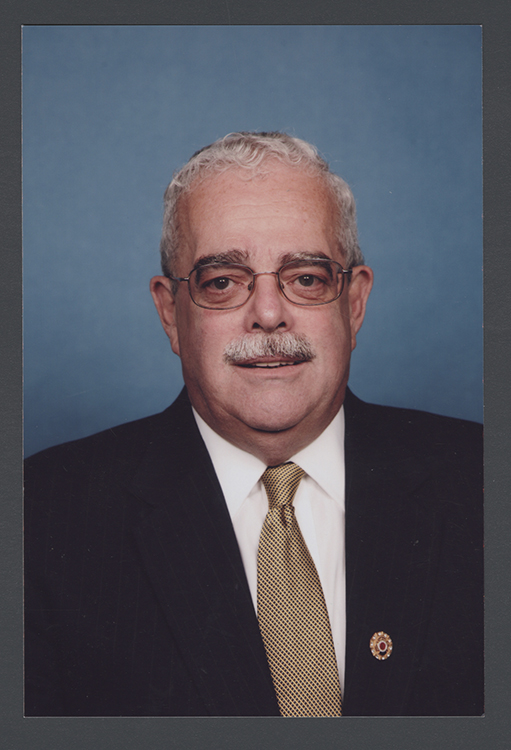

John Singleton Millson (October 1, 1808 – March 1, 1874) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician who served six consecutive terms as a U.S. Representative from Virginia from 1849 to 1861. Born in Norfolk, Virginia, he pursued an academic course in his youth before turning to the study of law. He was admitted to the bar in 1829 and commenced the practice of law in his native city, establishing himself as a member of the local legal community well before entering national politics.

Millson’s legal career in Norfolk provided the foundation for his later public service. As a young attorney, he built a practice that reflected the commercial and maritime character of the port city, and his professional standing helped position him for elective office. By the late 1840s, amid growing sectional tensions in the United States, he emerged as a Democratic candidate for Congress from Virginia, representing the interests of his constituents in a period of mounting national conflict over slavery and territorial expansion.

Millson was elected as a Democrat to the Thirty-first Congress and to the five succeeding Congresses, serving from March 4, 1849, to March 3, 1861. In the 1849 election, he was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives with 51.67 percent of the vote, defeating a Whig opponent identified as Watts. He was re-elected in 1851 with 59.58 percent of the vote, defeating Whig Leopold C. P. Cowper; in 1853 with 56.68 percent of the vote, defeating Whig Johnathan R. Chambliss and Independent Democrat William D. Roberts; and in 1855 with 53.29 percent of the vote, defeating an American Party candidate, again identified as Watts. In 1857 he was re-elected without opposition, and in 1859 he secured another term with 61.46 percent of the vote, defeating Independent candidates identified as Pretlow, Chandler, and Sykes. These successive victories reflected both his personal popularity and the strength of the Democratic Party in his district during the decade preceding the Civil War.

During his tenure in the House of Representatives, Millson contributed to the legislative process as a loyal member of the Democratic Party while occasionally breaking with the prevailing views of many Southern colleagues. He served as chairman of the Committee on Revolutionary Pensions during the Thirty-second Congress, overseeing matters related to benefits for veterans and their families of the Revolutionary era. His congressional service coincided with some of the most contentious debates in antebellum America, including disputes over the extension of slavery into the territories and the balance of power between free and slave states.

Millson is particularly notable as one of only two Southern Democrats to have voted against the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the other being Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. The act, passed in 1854, effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise by allowing the question of slavery in the Kansas and Nebraska territories to be decided by popular sovereignty. Millson’s opposition set him apart from most Southern members of his party and underscored his willingness to diverge from dominant regional sentiment on a critical national issue. His vote placed him in a small minority among Southern Democrats at a time when sectional loyalties were hardening and compromise was increasingly elusive.

After leaving Congress at the close of the Thirty-sixth Congress on March 3, 1861, Millson resumed the practice of law in Norfolk. His post-congressional years unfolded against the backdrop of the Civil War and Reconstruction, during which Virginia and his home city experienced occupation, economic disruption, and political realignment. Although he no longer held national office, his long experience in Congress and established legal reputation ensured that he remained a respected figure in his community.

John Singleton Millson died in Norfolk, Virginia, on March 1, 1874. He was interred in Cedar Grove Cemetery in Norfolk. His career spanned a transformative era in American history, and his six-term service in the House of Representatives, his chairmanship of the Committee on Revolutionary Pensions, and his distinctive vote against the Kansas-Nebraska Act marked him as a significant, if often understated, participant in the nation’s political life in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Congressional Record