John Vliet Lindsay (November 24, 1921 – December 19, 2000) was an American politician, lawyer, and public official who served as a Representative from New York in the United States Congress from 1959 to 1967 and as mayor of New York City from January 1966 to December 1973. A member of the Republican Party for most of his early political career, he later became a Democrat and sought the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination and the 1980 Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate from New York. He was also a regular guest host of the national television program Good Morning America and remained a prominent public figure long after leaving elective office.

Lindsay was born in New York City on West End Avenue to George Nelson Lindsay, a successful lawyer and investment banker, and the former Florence Eleanor Vliet. He grew up in an upper-middle-class family of English and Dutch descent; his paternal grandfather had migrated to the United States in the 1880s from the Isle of Wight, and his mother’s family had been established in New York since the 1660s. He attended the Buckley School in Manhattan and St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire before entering Yale University, where he was admitted to the class of 1944 and joined the Scroll and Key society. With the outbreak of World War II, he accelerated his studies and left Yale early in 1943 to join the United States Navy.

During World War II, Lindsay served as a Navy gunnery officer, ultimately attaining the rank of lieutenant. He saw extensive combat duty, earning five battle stars for his participation in the invasion of Sicily and a series of landings in the Asiatic-Pacific theater. After the war, he briefly lived as a ski bum and then trained for a short period as a bank clerk before returning to New Haven to complete his legal education. He received his law degree from Yale Law School in 1948, ahead of schedule, and was admitted to the bar in 1949. That same year he joined the New York law firm of Webster, Sheffield, Fleischmann, Hitchcock & Chrystie, rising to become a partner within four years as he built a reputation as a capable and ambitious young attorney.

In 1946, Lindsay met Mary Anne Harrison (1926–2004) at the wedding of Nancy Walker Bush, daughter of Senator Prescott Bush of Connecticut and sister of future President George H. W. Bush; Lindsay served as an usher and Harrison, a Vassar College graduate and distant relative of Presidents William Henry Harrison and Benjamin Harrison, was a bridesmaid. The couple married in 1949 and had three daughters and one son. As his legal career advanced, Lindsay increasingly gravitated toward politics. He helped found the Youth for Eisenhower club in 1951 and served as president of the New York Young Republican Club in 1952, aligning himself with the moderate, internationalist wing of the Republican Party. In 1955 he joined the U.S. Department of Justice as executive assistant to Attorney General Herbert Brownell, where he worked on civil liberties matters and contributed to the drafting and passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

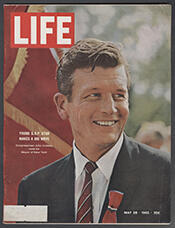

With the backing of Brownell and prominent Republicans such as Bruce Barton, John Aspinwall Roosevelt, and Edith Willkie, Lindsay entered electoral politics in 1958. That year he won the Republican primary and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as the congressman from New York’s 17th District, the so‑called “Silk Stocking” district centered on Manhattan’s Upper East Side but also encompassing the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village. A member of the Republican Party, John Vliet Lindsay contributed to the legislative process during four terms in office, serving from January 1959 to December 1965. His service in Congress occurred during a significant period in American history, and he established a liberal voting record that increasingly put him at odds with many in his own party. He was an early supporter of federal aid to education and of Medicare, and he advocated the creation of a federal Department of Housing and Urban Development and a National Foundation for the Arts and Humanities. Known as a maverick, he cast the lone Republican vote against a bill extending the Postmaster General’s power to impound obscene mail and was one of only two Republicans to oppose a bill permitting federal interception of mail from Communist countries. When party leaders questioned his stance, he quipped that Communism and pornography were the major industries of his district and that suppressing them would make it “a depressed area.” He voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1960 and 1964, the 24th Amendment to the Constitution, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, reinforcing his national profile as a liberal Republican.

In the 1965 New York City mayoral election, Lindsay ran as a Republican with the endorsement of the Liberal Party of New York in a three-way race. He defeated Democratic City Comptroller Abraham D. Beame and Conservative Party candidate William F. Buckley Jr., founder of National Review. His campaign, which capitalized on his youth and reform image, adopted as an unofficial motto a line from columnist Murray Kempton: “He is fresh and everyone else is tired.” Lindsay assumed office as mayor on January 1, 1966, and his tenure quickly became synonymous with the turbulence of late-1960s urban America. On his first day in office, the Transport Workers Union, led by Mike Quill, shut down subway and bus service in a citywide transit strike. Seeking to demonstrate solidarity with ordinary New Yorkers, Lindsay walked four miles from his hotel to City Hall, telling reporters, “I still think it’s a fun city,” a remark that columnist Dick Schaap later used sardonically in coining the term “Fun City.” The costly settlement of the transit strike, combined with rising welfare expenditures and economic decline, led Lindsay to seek a new municipal income tax, higher water rates, and a commuter tax from the New York State Legislature, inaugurating a series of fiscal and labor challenges that would mark his administration.

Lindsay’s mayoralty was defined by both ambitious reform efforts and intense controversy. In 1967 he was appointed to the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission) and served as its vice chairman. He played a major role in shaping the commission’s landmark report, which warned that the nation was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” When riots erupted in more than 100 American cities following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, Lindsay went directly to Harlem, speaking with residents and expressing his sorrow and commitment to fighting poverty. His visible presence and prior engagement with the community are widely credited with helping avert large-scale rioting in New York City. At the same time, his attempt to decentralize the city’s school system by granting broad authority to local school boards in neighborhoods such as Ocean Hill–Brownsville provoked a bitter confrontation with the United Federation of Teachers. The resulting series of citywide teachers’ strikes in 1968, tinged with racial and anti-Semitic overtones and pitting Black and Puerto Rican parents against largely Jewish teachers and administrators, lasted intermittently for seven months and left a lasting legacy of tension; Lindsay later called the episode his greatest regret. That year also saw a three-day Broadway strike and a nine-day sanitation strike, during which uncollected garbage piled up and sometimes caught fire in the streets, contributing to what Lindsay described as “the worst” period of his public life.

The late 1960s and early 1970s brought further crises. On February 10, 1969, a major snowstorm left 15 inches of snow across the city, and the slow pace of snow removal in outer-borough neighborhoods, especially eastern Queens, led to a political uproar and charges that Lindsay favored Manhattan over working- and middle-class communities elsewhere. His contentious visit to Queens amid unplowed streets and angry residents produced scenes that became emblematic of what critics called the “Lindsay Snowstorm,” reinforcing perceptions of mayoral indifference among some New Yorkers. In 1969, a backlash against his administration helped him lose the Republican mayoral primary to State Senator John Marchi, who was strongly supported by conservative Republicans including William F. Buckley Jr. In the Democratic primary that year, City Comptroller Mario Procaccino, running to Lindsay’s right, secured the nomination with a plurality and popularized the term “limousine liberal” to describe Lindsay and his affluent Manhattan supporters. Despite losing the Republican line, Lindsay remained on the ballot as the Liberal Party candidate, acknowledged that “mistakes were made,” and described being mayor of New York City as “the second toughest job in America.” Running a media-savvy campaign that highlighted both his errors and his achievements—such as increasing the police force and attracting new jobs while avoiding the large-scale riots that had devastated cities like Detroit and Newark—he won reelection with a plurality of the vote, drawing support from African American and Puerto Rican communities, liberal and professional-class Manhattanites, and many Jewish and other middle-class voters in neighborhoods such as Forest Hills and Kew Gardens in Queens and Brooklyn Heights in Brooklyn.

Lindsay’s second term was marked by further conflict with organized labor and the police. On May 8, 1970, during demonstrations in lower Manhattan against the Kent State shootings, the Cambodian Campaign, and the Vietnam War, construction workers mobilized by the New York State AFL–CIO attacked antiwar protesters in what became known as the “Hard Hat Riot.” Lindsay sharply criticized the New York City Police Department for failing to protect the demonstrators, prompting police union leaders to accuse him of undermining public confidence in the force. In the days that followed, thousands of construction workers, longshoremen, and white-collar workers rallied against the mayor, denouncing him as “the red mayor,” “traitor,” and “Commie rat.” In 1970, after The New York Times published Patrolman Frank Serpico’s allegations of widespread police corruption, Lindsay established the Knapp Commission to investigate the NYPD. The commission began its work in June 1970 and held public hearings starting in October 1971, issuing its final recommendations in December 1972. Many officers resented the mayor for initiating the probe; some heckled and booed him at police funerals, and the widow of slain officer Rocco Laurie publicly requested that Lindsay not attend her husband’s funeral in 1972. In 1971, the city was again disrupted when more than 8,000 members of AFSCME District Council 37, including drawbridge and sewage plant operators, went on strike, briefly halting bridge traffic and allowing raw sewage to flow into local waterways.

Nationally, Lindsay’s prominence made him a recurring figure in presidential politics. He was mentioned as a possible Republican vice-presidential nominee in 1968, but Southern conservatives opposed him, and Richard Nixon chose Spiro Agnew instead. His break with the Republican Party deepened after his 1969 primary defeat and his successful reelection as mayor on the Liberal Party line. In 1971, during his second term as mayor, Lindsay and his wife formally left the Republican Party and registered as Democrats. He declared that the move “recognizes the failure of 20 years in progressive Republican politics” and signaled his intention to fight for “new national leadership.” That same year he launched a brief and ultimately unsuccessful campaign for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination. He attracted favorable media attention and proved an effective fundraiser, performing relatively well in the early Arizona caucus, where he finished second to Senator Edmund Muskie and ahead of Senator George McGovern. However, his fifth-place showing in the March 14 Florida primary—behind George Wallace, Muskie, Hubert Humphrey, and Henry “Scoop” Jackson, though narrowly ahead of McGovern—badly damaged his prospects. Critics charged that he was neglecting New York City’s mounting fiscal and social problems, and protesters from Forest Hills, Queens, opposed to his support for low-income housing in their neighborhood, followed him on the campaign trail. After another disappointing result in the April 5 Wisconsin primary, Lindsay ended his presidential bid; Brooklyn Democratic leader Meade Esposito summed up the political consensus by saying, “I think the handwriting is on the wall; Little Sheba better come home.”

After leaving the mayor’s office at the end of 1973, Lindsay remained active in public life but never again held elective office. He made an unsuccessful bid to become the Democratic candidate in the 1980 U.S. Senate election in New York, failing to secure the nomination. He continued to practice law, engage in public affairs, and appear in the media, including as a regular guest host on Good Morning America, where his experience and name recognition kept him in the national spotlight. John Vliet Lindsay died in New York City on December 19, 2000, leaving a complex legacy as a liberal reformer whose congressional and mayoral careers unfolded during a transformative and often tumultuous era in American urban and political history.

Congressional Record