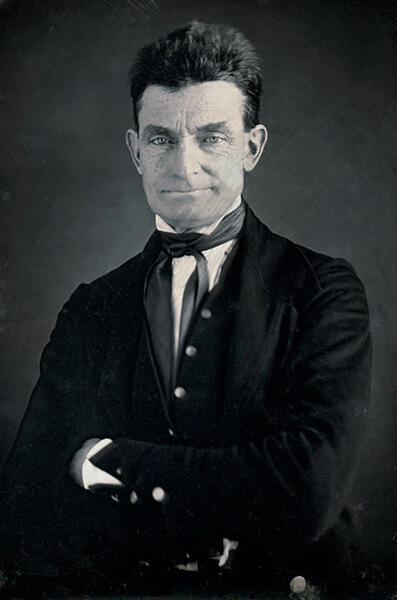

John Brown (abolitionist) (May 9, 1800–December 2, 1859) was an American anti-slavery militant best known for leading an armed raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859. His name has since become the one most commonly associated with “John Brown” in American historical memory, and he is widely regarded as one of the most radical and consequential figures in the antebellum struggle over slavery. A fervent Calvinist, he believed that slavery was a sin that could be eradicated only through direct, often violent, confrontation, and he devoted much of his adult life to organizing resistance to the institution across several states.

Brown was born in Torrington, Connecticut, and raised in a deeply religious family that opposed slavery. During his youth his family moved to the Western Reserve region of Ohio, where his father worked as a tanner and engaged in small-scale business. The frontier environment, combined with the strong antislavery convictions of his parents, shaped Brown’s early worldview. He briefly attended school and at one point considered studying for the ministry, but his formal education remained limited. From an early age he was exposed to African Americans, both enslaved and free, and he later recalled witnessing the mistreatment of enslaved people as a formative experience that convinced him slavery was incompatible with Christian morality and republican ideals.

As a young man, Brown married and attempted to establish himself in a series of trades and enterprises, including tanning, livestock dealing, land speculation, and various small businesses in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and later the Kansas Territory. His financial record was uneven, marked by repeated failures, debt, and bankruptcy, and he frequently moved his large family in search of more promising opportunities. Despite these reverses, he became increasingly involved in the abolitionist movement, forming connections with antislavery activists and African American communities. He participated in efforts to assist freedom seekers on what later came to be known as the Underground Railroad, helping enslaved people escape from bondage to free states and Canada.

Brown’s national prominence began with his activities in “Bleeding Kansas” in the mid-1850s, when the question of whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state led to violent conflict. Moving to the territory to support the free-state cause, he organized and led small bands of armed men in defense of antislavery settlers. In May 1856, following the sacking of the free-state town of Lawrence by proslavery forces, Brown and a group of followers carried out the Pottawatomie Creek killings, in which five proslavery settlers were seized and killed. This episode, shocking even to some antislavery allies, cemented Brown’s reputation as a man willing to use lethal force in the struggle against slavery and made him a polarizing figure in national politics.

Building on his Kansas experience, Brown developed a more ambitious plan to strike directly at slavery in the South. He traveled in the northern states and in Canada, raising funds and recruiting supporters among abolitionists, including some prominent New England intellectuals and reformers who later became known as the “Secret Six.” Brown envisioned establishing a base in the Appalachian Mountains from which small, mobile bands of armed men could raid plantations, free enslaved people, and trigger a widespread slave uprising. To prepare for this effort, he stockpiled weapons and gathered a small, racially integrated group of followers, including several of his own sons and a number of African American allies who shared his determination to confront slavery by force.

On the night of October 16, 1859, Brown led his long-planned raid on the federal armory and arsenal at Harpers Ferry, then in Virginia (now West Virginia). His force of fewer than two dozen men seized the armory and took several local citizens hostage, intending to capture weapons and retreat to the nearby mountains as enslaved people joined the insurrection. The expected mass uprising did not occur, and local militia units quickly surrounded the town. On October 18, U.S. Marines under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee stormed the engine house where Brown and his remaining followers had taken refuge. Brown was wounded and captured; several of his men, including two of his sons, were killed during the fighting, and others were taken prisoner or later executed.

Brown was tried in Charles Town, Virginia, on charges of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, conspiracy, and murder. The proceedings moved swiftly, and on November 2, 1859, he was convicted on all counts and sentenced to death. Throughout the trial and in the weeks leading up to his execution, Brown spoke and wrote with calm defiance, insisting that his actions were motivated by a desire to free the enslaved and appealing to a higher moral law above human statutes. His conduct, including his refusal to plead insanity and his dignified demeanor, won him admiration among many in the North, who came to view him as a martyr to the antislavery cause, even as most southern whites saw him as a terrorist and proof of northern hostility to their way of life.

John Brown was hanged in Charles Town on December 2, 1859. His execution was witnessed by a large military presence and by observers from across the South, reflecting the intense national interest his case had generated. News of his death and the publication of his final letters and statements further inflamed sectional tensions. In the North, church bells tolled in his honor, memorial meetings were held, and abolitionists invoked his name as a symbol of uncompromising resistance to slavery. In the South, the raid and its aftermath deepened fears of slave insurrection and northern conspiracy, contributing to the hardening of positions that would soon lead to secession and the Civil War. Over time, Brown’s legacy has remained contested, with historians and the public alternately emphasizing his religious zeal, his resort to violence, and his role in hastening the end of American slavery, but his 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, endures as the defining act of his life and the central reason he is the John Brown most often referred to in American history.

Congressional Record