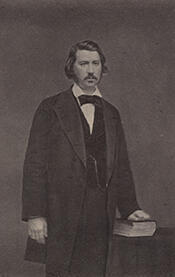

John Edward Bouligny (February 5, 1824 – February 20, 1864) was an American politician who served as a Representative from Louisiana in the United States Congress from 1859 to 1861. A member of the Know Nothing movement’s anti-immigrant American Party, also known as the American Party, he represented Louisiana’s 1st congressional district for one term during a critical period in the nation’s history leading up to the Civil War. His tenure in the House of Representatives was marked by his participation in the legislative process on behalf of his constituents and by his notable refusal to abandon his seat when Louisiana seceded from the Union.

Bouligny emerged as a significant political figure in Louisiana in the late 1850s. In 1859, he sought the American Party nomination for the U.S. House of Representatives in what contemporaries described as a “brisk, close and earnest” contest. At the party convention he narrowly secured the nomination, edging state representative Charles Didier Dreux by just two votes and defeating Judge T. G. Hunt Jr., an old-line Whig. In the general election of November 1859, Bouligny won the seat with a plurality of 49.13 percent of the vote, defeating former Democratic representative Emile La Sére and States Rights candidate Charles Bienvenu. His victory sent him to Washington as part of the 36th Congress, where he took his place among a fracturing national legislature.

During his term in Congress, Bouligny contributed to the legislative process as a member of the House Committee on Private Land Claims. Serving from 1859 until 1861, he participated in debates and votes at a time of mounting sectional tension. According to later analysis by GovTrack, Bouligny missed 197 of 433 roll call votes during his single term, a record that reflects both the turbulence of the period and the complex political environment in which he operated. Nonetheless, he remained engaged in national politics and, in the 1860 presidential election, publicly supported the Northern Democratic candidate, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, aligning himself with a faction that sought to preserve the Union through compromise.

The defining episode of Bouligny’s congressional career came with the secession crisis. Louisiana formally withdrew from the United States on January 26, 1861, prompting the rest of the state’s congressional delegation to resign or vacate their seats. Bouligny, however, took a different course. On February 5, 1861—his thirty-seventh birthday—he delivered a speech on the floor of the House of Representatives in which he declared his strong opposition to Louisiana’s secession. He asserted that he answered not to the state’s secession convention but to the people who had elected him, and he stated that if his constituents demanded his resignation he would comply, but would “remain a Union man.” True to this position, he refused to resign and remained in Washington, continuing to serve until the expiration of his term on March 3, 1861. During this same period, in February 1861, he was the only Louisianan to participate in the Peace Conference of 1861, an effort by representatives of various states to find a last-minute compromise to avert civil war.

Bouligny’s stance made him unique among Louisiana’s federal representatives. He was the only member of Congress from Louisiana who did not resign or vacate his seat after the state seceded, underscoring both his personal commitment to the Union and the political isolation that came with that choice. His service in Congress thus occurred during one of the most significant and volatile moments in American history, and his actions placed him among the small group of Southern Unionists who attempted to bridge the widening divide between North and South.

After leaving Congress at the close of the 36th Congress in March 1861, Bouligny’s public role diminished as the Civil War engulfed the country. He lived through the early years of the conflict but did not return to national office. John Edward Bouligny died on February 20, 1864. His brief but consequential congressional career, particularly his refusal to abandon his seat and his participation in the Peace Conference of 1861, left a distinct mark on the historical record of Louisiana’s representation in the United States Congress during the secession crisis.

Congressional Record