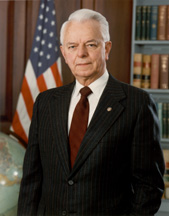

Jennings Randolph (March 8, 1902 – May 8, 1998) was an American politician from West Virginia whose congressional career spanned more than half a century. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in the United States House of Representatives from 1933 to 1947 and in the United States Senate from 1958 to 1985, contributing to the legislative process during twelve terms in Congress. He was the last living member of Congress to have served during the first 100 days of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration. Randolph retired from the Senate in 1985 and was succeeded by John D. “Jay” Rockefeller IV.

Randolph was born in Salem, Harrison County, West Virginia, the son of Idell (Bingham) and Ernest Fitz Randolph. He was named after William Jennings Bryan, reflecting his family’s admiration for the populist Democratic leader. Public service was a family tradition: both his grandfather and his father served as mayors of Salem. He attended the local public schools and graduated from Salem Academy in 1920, then from Salem College in 1922. His early life and ambitions were notably influenced by a commencement address at Salem College delivered by author Napoleon Hill; Randolph later urged Hill to turn that speech into the book “Think and Grow Rich,” and Randolph’s letter to Hill is reproduced in the volume.

Following his graduation, Randolph embarked on a career in journalism and education. In 1924 he engaged in newspaper work in Clarksburg, West Virginia, and in 1925 he became associate editor of the West Virginia Review in Charleston. From 1926 to 1932 he headed the department of public speaking and journalism at Davis and Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia, and he served as a trustee of both Salem College and Davis and Elkins College. His expertise in oratory led him to co-author, with James A. Bell, a practical manual on rhetoric titled “Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen… : A Practical Guide to Public Speaking,” published in 1939. On February 18, 1933, he married Mary Katherine Babb; she remained his partner throughout most of his public career until her death from cancer on March 10, 1981. In her memory, the Mary Babb Randolph Cancer Center at West Virginia University was named in her honor.

Randolph first sought election to the United States House of Representatives in 1930 but was unsuccessful. He ran again in 1932 and won, taking office on March 4, 1933, as part of the Democratic wave that accompanied Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. He was re-elected six times and served in the House until January 3, 1947. During his tenure, he chaired the House Committee on the District of Columbia during the Seventy-sixth through Seventy-ninth Congresses and the House Committee on Civil Service in the Seventy-ninth Congress. As a representative, he was the principal sponsor of the Randolph–Sheppard Act of 1936, which granted blind persons preference in federal contracts for food service stands and other concessions on federal property. The law is widely regarded as one of the earliest and most successful affirmative action measures, providing blind workers with secure employment and greater independence than earlier sheltered workshop models.

Randolph’s House career unfolded during a transformative era in American governance. He was deeply involved in aviation policy, an area in which he became a nationally recognized advocate. In 1938 he sponsored the Civil Aeronautics Act, which transferred federal civil aviation responsibilities from the Department of Commerce to a new independent agency, the Civil Aeronautics Authority, empowering it to regulate airline fares and routes. He later co-authored the Federal Airport Act and supported legislation that created the Civil Air Patrol, the National Air and Space Museum, and National Aviation Day. An aviation enthusiast himself, Randolph often flew more than once a day to visit constituents in West Virginia and commute to Washington, and he was the founder and first president of the Congressional Flying Club. He also promoted energy innovation, proposing the Synthetic Liquid Fuels Act in 1942 to fund the conversion of coal into liquid fuels. To demonstrate the feasibility of synthetic fuels, in November 1943 he flew with a professional pilot from Morgantown, West Virginia, to National Airport in Washington, D.C., in a small aircraft powered by gasoline derived from coal. With the support of Interior Secretary Harold Ickes and Senator Joseph C. O’Mahoney, the Synthetic Liquid Fuels Act was approved on April 5, 1944, authorizing $30 million for demonstration plants.

Randolph was defeated for re-election to the House in the Republican landslide of 1946, but he remained active in education, business, and public affairs. From 1935 to 1953 he had a long association with Southeastern University in Washington, D.C., serving as a professor of public speaking, and he later became dean of its School of Business Administration from 1952 to 1958. In February 1947 he joined Capital Airlines in Washington as assistant to the president and director of public relations, positions he held until April 1958, when he resigned to focus on a campaign for the United States Senate. During these years he also developed a growing interest in institutional approaches to peace and conflict resolution, themes that would later shape his Senate work.

Randolph returned to Congress as a senator from West Virginia after winning a special election on November 4, 1958, to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Senator Matthew M. Neely. He took his seat on November 5, 1958, and subsequently won full six-year terms in 1960, 1966, 1972, and 1978, serving continuously until January 3, 1985. During this period he was chairman of the Senate Committee on Public Works in the Eighty-ninth through Ninety-fifth Congresses and of its successor, the Committee on Environment and Public Works, in the Ninety-fifth and Ninety-sixth Congresses. In these roles he helped shape major federal infrastructure and environmental policy, including the Airport–Airways Development Act, which created the Airport Trust Fund, and he co-authored the Appalachian Regional Development Act, ensuring that provisions for rural airport development were included to support economic growth in Appalachia. In recognition of his contributions to transportation, he received the George S. Bartlett Award for road transportation in 1971.

Throughout his Senate career, Randolph was a consistent supporter of civil rights and voting rights legislation. He voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1960, 1964, and 1968, the 24th Amendment to the Constitution abolishing the poll tax in federal elections, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall as the first African American justice of the United States Supreme Court. He became best known nationally for his long campaign to lower the voting age. Beginning in 1942, while still in the House, he introduced a constitutional amendment to grant the franchise to citizens aged 18 to 21, arguing that young Americans old enough to fight in World War II should be allowed to vote. He reintroduced the proposal repeatedly over the ensuing decades. In 1970, Congress amended the Voting Rights Act to lower the voting age to 18 in federal, state, and local elections, but the Supreme Court’s decision in Oregon v. Mitchell held that Congress could only mandate the lower age for federal elections. Randolph was among the senators who then reintroduced a constitutional amendment, which was approved by Congress and ratified by three-fourths of the states in 1971 as the Twenty-sixth Amendment—one of the fastest ratifications in American history, completed in 107 days. Following a request from President Richard Nixon, on February 11, 1972, Randolph personally escorted Ella Mae Thompson Haddix to the Randolph County Courthouse in Elkins, West Virginia, where she became the first 18-year-old registered voter in the United States.

Randolph’s record on gender equality and women’s rights was more complex. On August 26, 1970, the fiftieth anniversary of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, he drew widespread criticism for remarks about the Women’s Liberation Movement. As feminists organized a nationwide Women’s Strike for Equality and presented Senate leaders with a petition supporting the Equal Rights Amendment, Randolph derided some protesters as “braless bubbleheads” and contended that radical activists, particularly those supporting what he termed the “right to unabridged abortions,” did not speak for all women. He later acknowledged that his “bubbleheads” comment was “perhaps ill-chosen,” and he went on to support the Equal Rights Amendment; when the amendment passed the Senate in 1972, Randolph was a co-sponsor.

In addition to his work on civil rights, aviation, and energy, Randolph was a leading advocate for institutional mechanisms to promote peace. In 1946 he introduced legislation to establish a Department of Peace, intended to strengthen the nation’s capacity to manage international conflicts through both military and nonmilitary means. In the 1970s and 1980s he joined Senators Mark Hatfield and Spark Matsunaga and Representative Dan Glickman in efforts to create a national institution dedicated to peace studies and conflict resolution. After announcing his retirement from Congress in 1984, Randolph played a key role in securing passage of the United States Institute of Peace Act. To ensure its enactment and funding, the legislation was attached to the Department of Defense Authorization Act of 1985, and its approval was widely seen as a tribute to Randolph’s long public service. The Jennings Randolph Program at the U.S. Institute of Peace, which awards fellowships to scholars, policymakers, journalists, and other professionals from around the world, was later named in his honor.

Randolph’s influence extended beyond legislation into international agricultural and energy policy. He served as de facto chairman of the Agri-Energy Roundtable (AER), a nongovernmental organization accredited by the United Nations, and led United States delegations to seven AER annual conferences in Geneva, Switzerland, between 1981 and 1987. His interest in infrastructure and transportation was commemorated in several major facilities bearing his name, including Jennings Randolph Lake, located in Mineral County, West Virginia, and Garrett County, Maryland; the Jennings Randolph Bridge carrying U.S. Route 30 across the Ohio River between Chester, West Virginia, and East Liverpool, Ohio; and, within West Virginia, Interstate 79, known as the Jennings Randolph Expressway.

Randolph’s family remained prominent in public life and broadcasting. His son, Jay Randolph, became a longtime television sportscaster, working for NBC and for KSDK in St. Louis on St. Louis Cardinals baseball broadcasts. His grandson, Jay Randolph Jr., served as lead anchor of the PGA Tour Network on XM Satellite Radio and hosted a sports talk show on St. Louis radio station KFNS before his death in 2022. Jennings Randolph himself spent his final years largely out of the public eye. He died in St. Louis, Missouri, on May 8, 1998, at the age of 96, and was interred in the Seventh Day Baptist Cemetery in his hometown of Salem, West Virginia, closing a life that had begun and ended in the same small community but had left a lasting imprint on national policy and institutions.

Congressional Record