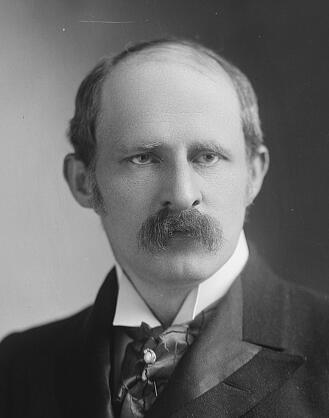

Jefferson Monroe Levy (April 16, 1852 – March 6, 1924) was a three-term U.S. Congressman from New York, a leader of the New York Democratic Party, and a prominent real estate and stock speculator who played a central role in the preservation and restoration of Monticello, the historic home of Thomas Jefferson. Born in New York City to Jonas Levy and Frances (Phillips) Levy, an American Jewish couple, he was one of five children. His father was a merchant and sea captain, and his mother was a descendant of Jonas Phillips and his wife Rebecca Machado. His mother’s parents had immigrated from Germany and London in the mid-eighteenth century, and his father’s Sephardic Jewish ancestors, also from London, were among the first Jewish settlers of Savannah, Georgia, arriving in 1733. Levy and his siblings attended both public and private schools in New York City, growing up in a family with deep roots in early American Jewish history.

Levy pursued legal studies and graduated from the New York University School of Law in 1873. He was admitted to the bar and commenced the practice of law in New York City. Alongside his legal work, he quickly developed a successful career in real estate investment and finance, becoming known as a skilled and energetic speculator in both real estate and stocks. His growing fortune and prominence in New York’s business community helped position him as an influential figure in the city’s Democratic politics, where he rose to be regarded as a leader within the New York Democratic Party.

Levy’s life and public reputation were closely intertwined with Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s home near Charlottesville, Virginia. His uncle, Uriah P. Levy, the first Jewish commodore of the United States Navy (then the highest rank in the service), had purchased Monticello and related property in 1834 and spent considerable sums to restore and preserve the house and grounds, which he used as a summer retreat. During the American Civil War, Confederate authorities took control of the property, but after the war, the lawyers for Uriah Levy’s estate succeeded in regaining it for his heirs. In 1879, at the age of 27, Jefferson Monroe Levy bought out the other heirs of his uncle for $10,050 (approximately $285,958 in 2024) and took control of Monticello. At that time, the estate had been reduced to 218 acres, and the house and grounds were in severe disrepair, the result of neglect by the overseer Joel Wheeler and lengthy litigation among the heirs following Uriah Levy’s death.

Over the ensuing decades, Levy devoted a considerable part of his fortune to restoring and preserving Monticello and its grounds. He purchased an additional 500 acres to expand the property and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars repairing and rehabilitating the mansion and landscape. The restoration work was directed on-site by Thomas Rhodes, Levy’s superintendent at Monticello. Levy spent roughly four months each year at the estate and became active in the civic life of Charlottesville. In 1880 he financed the restoration of the Town Hall in Charlottesville, originally built as a theater, which was renamed the Levy Opera House in his honor. He allowed the public to visit Monticello, sometimes receiving as many as sixty visitors a day, and was widely recognized for his hospitality and his commitment to maintaining the property as a “sacred shrine” to Jefferson.

Levy’s political career developed alongside his legal and business pursuits. A member of the Democratic Party, he was elected as a Democrat to the Fifty-sixth Congress and served as a Representative from New York from March 4, 1899, to March 3, 1901. His service in Congress occurred during a significant period in American history at the turn of the twentieth century, and he participated in the legislative process while representing the interests of his New York constituents. He was not a candidate for renomination in 1900 and returned to New York City, where he resumed the practice of law and continued to manage his extensive real estate and stock investments. In addition to his congressional work, he was active in civic and patriotic organizations; in 1894 he became a member of the New York State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, where he was assigned national membership number 4539 and state-society number 439.

Levy returned to national office a decade later. He was elected again as a Democrat to the Sixty-second and Sixty-third Congresses, serving from March 4, 1911, to March 3, 1915. During these additional two terms, he continued to represent New York in the House of Representatives and to participate in the democratic process as part of the House’s legislative deliberations. He did not seek renomination in 1914 and once more resumed his law practice in New York City. His ownership of Monticello became a subject of national debate during this period. Beginning around 1909, Maud Littleton, wife of New York Congressman Martin W. Littleton, led a campaign urging Congress to purchase Monticello and convert it into a government-run national monument to Thomas Jefferson. The campaign was often heated and included newspaper attacks that disparaged Levy’s private ownership of the property. In response, the Albemarle Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution in November 1912 unanimously adopted a resolution defending Levy, praising the care with which he preserved Monticello, his generosity in opening it to the public, and opposing efforts to seize private property “by the strong arm of Government against the will of the individual.”

Although the election of President Woodrow Wilson in 1912 increased the likelihood of congressional authorization to purchase Monticello, no such authorization was ultimately achieved during Levy’s lifetime. In the post–World War I recession, Levy’s fortune declined, and the financial burden of maintaining the estate grew heavier. In 1923 he agreed to sell Monticello to the newly organized Thomas Jefferson Foundation, accepting a down payment and mortgage arrangement. The Foundation, created to preserve the property as a historic site, raised the necessary funds to complete the purchase and thereafter operated Monticello as a house museum. Levy’s long stewardship of the estate, following that of his uncle, ensured that the house and grounds survived in a condition that made their later institutional preservation possible.

Beyond his legal, political, and preservation activities, Levy was involved in various organizations and causes. He served on the board of the American Boy Scouts but resigned in 1910, along with publisher William Randolph Hearst, in protest over what they regarded as poor fundraising practices. His prominence in public life was reflected in cultural recognition as well; a portrait of Levy was painted by the artist George Burroughs Torrey. Despite his active public and social life, Levy never married. During his stays at Monticello, his mother and a sister acted as hostesses, receiving guests and assisting in the social obligations associated with his role as owner of the historic estate.

Jefferson Monroe Levy died in New York City on March 6, 1924. He was interred in Beth Olam Cemetery in Brooklyn, a burial ground associated with Congregation Shearith Israel, the historic Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in Manhattan, and he was buried near his uncle, Commodore Uriah P. Levy. In the decades after his death, his and his family’s contributions to the preservation of Monticello received renewed recognition. After 1985, Daniel P. Jordan, president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, undertook efforts to honor the Levy family at Monticello, including the restoration of Rachel Levy’s gravesite and the commissioning of a scholarly monograph on the family’s role in saving the house. In 2001 the Thomas Jefferson Foundation published The Levy Family and Monticello, 1834–1923: Saving Thomas Jefferson’s House, and that same year Free Press/Simon & Schuster released Marc Leepson’s Saving Monticello: The Levy Family’s Epic Quest to Rescue the House that Jefferson Built, both works documenting the central place of Jefferson Monroe Levy and his relatives in the history of Jefferson’s home.

Congressional Record