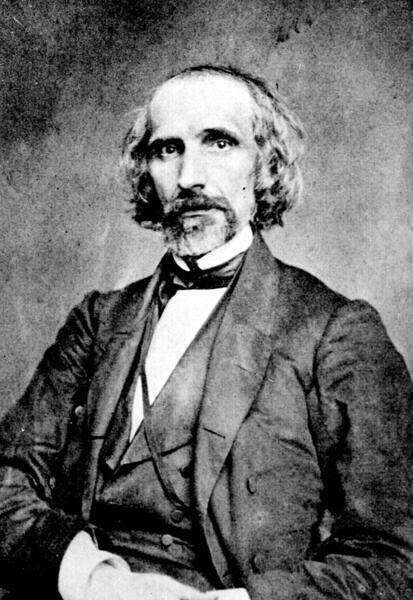

James Alexander Seddon (July 13, 1815 – August 19, 1880) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician from Virginia who served two terms in the United States House of Representatives and later became Confederate States Secretary of War during the American Civil War. Born in Richmond, Virginia, he was of delicate health from an early age, a condition that shaped much of his youth and later career. Because of his frailty, Seddon was educated primarily at home and became largely self-taught, developing strong intellectual habits and an early interest in law and public affairs.

At the age of twenty-one, Seddon entered the University of Virginia School of Law, then one of the leading legal institutions in the South. After completing his legal studies, he returned to Richmond and established a successful law practice, quickly gaining a reputation for his ability and learning at the bar. On December 23, 1845, he married Sarah Bruce in Richmond, Virginia, forming a union that anchored his personal life during a period of increasing public prominence. His professional success and growing political engagement brought him into the ranks of the Democratic Party at a time of intense sectional and partisan conflict in national politics.

In 1845, the Democratic Party nominated Seddon for a seat in the United States House of Representatives from Virginia. He was elected that year with 52.28 percent of the vote, defeating Whig candidate John Minor Botts. Serving in the Twenty-ninth Congress, he represented Virginia as a Democrat and contributed to the legislative process during a significant period in American history, participating in debates over issues that reflected the growing sectional tensions of the era. Although he was renominated in 1847, he declined to run again at that time because of disagreements with elements of the party platform. Returning to politics two years later, Seddon was reelected to Congress in 1849 with 53.64 percent of the vote, again defeating Botts, and he served in the Thirty-first Congress from December 1849 until March 1851. Owing to his continuing poor health, he declined another nomination at the end of this term and withdrew from national office.

After leaving Congress, Seddon retired from the daily pressures of public life to “Sabot Hill,” his plantation located along the James River above Richmond. From there he remained an influential figure in Virginia’s political circles and a committed advocate of Southern rights. As the sectional crisis deepened, he emerged as a strong proponent of secession. Nevertheless, in early 1861 he participated in last-ditch efforts to avert war, serving as a delegate to the Peace Conference of 1861 in Washington, D.C., which sought, unsuccessfully, to devise a compromise to prevent the impending Civil War. Later that same year, after the secession of the Southern states, he took part in the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States, helping to shape the new Confederate government.

Seddon’s prominence in Confederate political life led President Jefferson Davis to appoint him as the fourth Confederate States Secretary of War in November 1862, succeeding George W. Randolph. A strong advocate of secession and an ardent supporter of the Confederate cause, he assumed office at a moment of acute military and logistical strain. Upon taking charge of the War Department, he inherited a conscription system established by the Confederate Conscription Act of April 1862, which drafted white males aged eighteen to thirty-five. Seddon directed the rigorous enforcement of this system through the Conscription Bureau in an effort to address chronic manpower shortages in the Confederate armies. His tenure also coincided with severe economic hardship on the home front. In the wake of the Richmond Bread Riot of April 2, 1863—when a mob of hungry women took to the streets of the Confederate capital demanding food and relief—the crisis in Confederate supply and morale drew national attention, including a front-page article in The New York Times on April 8, 1863, under the headline “Bread Riot in Richmond. Three Thousand Hungry Women Raging in the Streets…”

As Secretary of War, Seddon was deeply involved in strategic deliberations at the highest levels of the Confederate government. In May 1863, he joined President Jefferson Davis in suggesting to General Robert E. Lee that significant forces be detached from the Army of Northern Virginia to relieve Union pressure on Vicksburg, Mississippi, a critical Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. Lee objected to this proposal and instead launched his invasion of the North, culminating in the Gettysburg Campaign and the Confederate defeat in Pennsylvania. Throughout his more than twenty-four months in office—making him the longest-serving of the Confederacy’s five secretaries of war—Seddon grappled with the immense challenges of sustaining the Confederate war effort in the face of mounting military setbacks, resource shortages, and internal dissent. He remained in the post until January 1, 1865, when he resigned and retired from public life to his plantation, and he was succeeded as Secretary of War by former U.S. Vice President John C. Breckinridge.

Following the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865, Seddon’s prominence in the Confederate government made him a target for federal authorities. He was arrested by Union forces in May 1865 and imprisoned for approximately seven months at Fort Pulaski, where he faced the possibility of charges related to the alleged mistreatment of Union prisoners during the war. Ultimately, President Andrew Johnson ordered that the charges be dropped, and Seddon was released without trial. After his release, he returned permanently to private life at Sabot Hill in Goochland County, Virginia, withdrawing from formal political activity and living quietly in retirement.

James Alexander Seddon died in Goochland County, Virginia, on August 19, 1880. He was buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, a resting place for many of the South’s political and military leaders. His career spanned antebellum service in the United States Congress, high office in the Confederate government, and a long postwar retirement marked by the lingering consequences of the conflict in which he had played a central administrative role.

Congressional Record