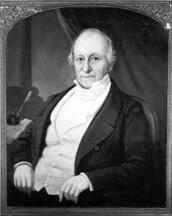

James Iredell was born on October 5, 1751, in Lewes, England, the eldest of five surviving children of Francis Iredell, a Bristol merchant, and his wife Margaret McCulloch of Dublin, Ireland. The failure of his father’s business and deteriorating health prompted the family to seek better prospects for James in the American colonies. In 1767, at the age of 17, he emigrated to North Carolina, where relatives helped secure him a position in the British customs service as deputy collector, or comptroller, of the port of Edenton. Raised the grandson of a clergyman, Iredell remained a devout Anglican throughout his life, and his surviving writings reflect a sustained interest in spirituality and metaphysics beyond simple adherence to organized religion.

While employed at the customs house in Edenton, Iredell began reading law under Samuel Johnston, a prominent attorney who would later serve as governor of North Carolina. He was admitted to the bar in 1771 and quickly established himself as a capable lawyer. In 1773, he married Johnston’s sister, Hannah Johnston; although the couple experienced twelve childless years at the outset of their marriage, they ultimately had four children, including James Iredell Jr., who would later become governor of North Carolina. In 1774, Iredell was promoted to collector for the port of Edenton, solidifying his position in the colony’s legal and commercial life even as political tensions with Great Britain intensified.

Despite his employment by the British government, Iredell emerged as a strong supporter of American independence. In 1774, at age 23, he published “To the Inhabitants of Great Britain,” an influential essay challenging the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy over the American colonies and establishing him as North Carolina’s leading political essayist of the period. His treatise “Principles of an American Whig” anticipated and echoed themes later embodied in the Declaration of Independence. During the Revolutionary era, he helped organize North Carolina’s court system and, in 1778, was elected a judge of the state’s superior court. From 1779 to 1781 he served as attorney general of North Carolina, and in 1787 the state assembly appointed him a commissioner to compile and revise the state’s laws, a project published in 1791 as “Iredell’s Revisal.”

Iredell was a prominent Federalist in North Carolina and a vigorous advocate for the new federal Constitution. Although financial constraints prevented him from serving as a delegate to the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, he corresponded regularly with North Carolina’s delegates and became the floor leader for the Federalists at the 1788 Hillsborough convention, where he argued unsuccessfully for ratification. After the convention declined to ratify, he joined William R. Davie in publishing the convention debates at their own expense to promote understanding of the proposed Constitution across the state. North Carolina later ratified the Constitution after the addition of the Bill of Rights. On February 8, 1790, President George Washington nominated Iredell as an associate justice of the newly established Supreme Court of the United States; he was confirmed by the Senate on February 10, 1790, and sworn into office on May 12, 1790. The early Supreme Court’s docket was light, and the justices were required to “ride circuit” under the Judiciary Act of 1789, traveling extensively to hear cases in the eastern, central, and southern circuits.

During his tenure on the Supreme Court, which lasted from 1790 until his death in 1799, Iredell authored several opinions that became foundational in American constitutional law. In Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), he was the lone dissenter from the Court’s holding that a state could be sued in federal court without its consent; public and political opinion largely sided with Iredell, and the Eleventh Amendment, adopted in 1795, effectively reversed the decision. In Calder v. Bull (1798), he joined a unanimous Court in holding that the Constitution’s Ex Post Facto Clause applied only to criminal laws, but his separate opinion was especially significant for its insistence that courts may invalidate only those state actions that violate explicit constitutional text, not abstract “principles of natural justice.” His reasoning in Calder, and in his essay “To the Public,” is regarded as an early and influential articulation of judicial review, anticipating themes later developed in Marbury v. Madison (1803). His charge to the federal grand jury in Fries’ Case has also been cited as evidence that some framers understood the First Amendment’s protection of the press primarily in terms of freedom from prior restraint, reflecting his reliance on Sir William Blackstone’s narrow formulation.

Iredell’s public career intersected with the institution of slavery in complex and often contradictory ways. Like contemporaries such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, he openly condemned the slave trade and expressed hope for eventual abolition, while continuing to own enslaved people throughout his life. In 1786, he reported owning 14 slaves, and both he and his wife Hannah owned slaves at the time of their deaths. As a lawyer, he participated in both abolitionist and pro-slavery matters: in 1777 he and William Hooper assisted more than 40 formerly enslaved people emancipated by Quakers in northeastern North Carolina after the General Assembly ordered their seizure and resale, yet in other instances he facilitated slave sales for clients and, in 1769, helped his father sell a runaway slave. In constitutional debates, he defended Article I, Section 9, Clause 1—the Slave Trade Clause—on pragmatic grounds, arguing that without it states such as South Carolina and Georgia would not ratify the Constitution, and that acceptance of this “evil” was necessary to secure a framework that might, “though at a distant period,” advance “the interests of humanity” and set an example for abolition. He nonetheless maintained that moral judgment on slavery ultimately rested “between the individuals’ consciences and God.”

Within his household and personal affairs, Iredell’s relationship to slavery displayed both paternalistic “humanity” and continued ownership. Surviving records identify several enslaved people he owned, including Peter, Peter’s wife Sarah, Edy, Dundee, and Hannibal. His brother Arthur at one point intended to transfer additional enslaved people inherited from their father, Thomas, to James, though the transaction was later reversed. Over time, Iredell manumitted some of those he enslaved, notably Peter, Edy, and Dundee, whom he freed in 1793 when the family moved from Philadelphia back to Edenton. Peter, who had long traveled with Iredell, became a woodcutter in Philadelphia and continued to work for Iredell on a hired basis when the justice visited the city. Judicial historian Willis Whichard has emphasized the closeness of this relationship, noting that Iredell later praised another servant by comparing his performance to Peter’s. Despite such individual acts of manumission, Iredell and his wife remained slaveholders at their deaths, a fact that continues to shape historical assessments of his legacy.

James Iredell’s life concluded amid the physical demands of early federal judicial service. The Judiciary Act’s requirement that Supreme Court justices ride circuit imposed arduous travel across the young republic, and this burden contributed to the deterioration of his health. He died suddenly on October 20, 1799, in Edenton, North Carolina, at the age of 48, while still serving as an associate justice of the Supreme Court. His influence endured in American jurisprudence and public memory: Iredell County, North Carolina, established in 1788, was named in his honor; during World War II, the Liberty ship SS James Iredell bore his name; and the James Iredell House in Edenton was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970. He has also appeared as a character in historical fiction, notably in Natalie Wexler’s novel “A More Obedient Wife: A Novel of the Early Supreme Court,” which centers on his wife Hannah and her friend Hannah Wilson. His son, James Iredell Jr., went on to serve as governor of North Carolina, extending the family’s prominence in state and national affairs.

Congressional Record