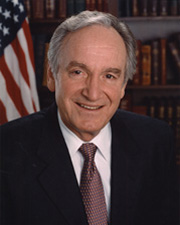

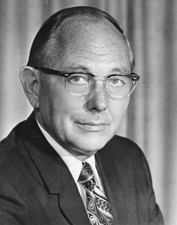

Harold Everett Hughes (February 10, 1922 – October 23, 1996) was an American politician who served as the 36th Governor of Iowa from 1963 until 1969 and as a United States Senator from Iowa from January 3, 1969, to 1975. Initially active in politics as a Republican, he changed his party affiliation to the Democratic Party in 1960 and became nationally known as a liberal Midwestern governor, a critic of the Vietnam War, and a leading advocate for the treatment of alcoholism and drug addiction.

Hughes was born in Ida Grove, Iowa, in 1922, the son of Lewis C. Hughes and Etta Estelle (Kelly) Hughes. He grew up in a heavily Republican area and was raised in the Methodist faith. In 1940 he attended the University of Iowa on a football scholarship, but he left the university after marrying Eva Mercer in August 1941. The couple had three daughters. On June 1, 1942, tragedy struck when his brother Jesse was killed in a car accident after their vehicle struck a concrete bridge and fell into a river 15 feet below. Jesse and another young man, Leroy Conrad, were to be inducted into the Army the following week under the Selective Service system, and two young women also died in the crash. Hughes later attributed Jesse’s death as a leading cause of his deepening alcoholism and his renunciation of his Methodist faith.

Hughes was drafted into the United States Army in 1942 during World War II. He served in the North African campaign and was court-martialed for assaulting an officer, after which he was sent to fight with the 16th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division in Sicily in 1943. During the Italian campaign he became ill, and another soldier took his place on a landing craft at Anzio; the craft exploded, killing his replacement and many others. Hughes himself was sent back to the United States for the remainder of the war after contracting jaundice and malaria. After the war he returned to Iowa, where his struggles with alcoholism intensified over the following years.

Hughes’s interest in politics grew out of his work in the trucking industry. He became a manager of a local trucking business and then began organizing independent truckers. He founded the Iowa Better Trucking Bureau, which brought him into broader public affairs and eventually to service on the Iowa State Commerce Commission. From 1958 to 1962 he served on the commission, including a term as its chairman, work that also brought him into contact with the federal Interstate Commerce Commission and national politics. During this period he experienced a personal crisis: in 1952, after years of alcoholism, he attempted suicide, later describing in his autobiography how he climbed into a bathtub with a shotgun, intending to kill himself, but instead cried out to God for help. He reported a profound spiritual experience that led him to renewed religious faith, intensive Bible study, and consideration of a career in the ministry. He embraced the Alcoholics Anonymous program of recovery and in 1955 started an AA group in Ida Grove. Though he had a brief relapse in 1954, he resumed sobriety and became a public advocate for recovery.

Originally a Republican, Hughes grew up in a Republican stronghold but was persuaded to switch parties as his views and alliances evolved. He formally changed his affiliation to the Democratic Party in 1960. That same year he ran for governor of Iowa as a Democrat but lost the Democratic primary to Edward McManus by 28,448 votes; McManus went on to lose the general election to Republican Norman A. Erbe. Undeterred, Hughes ran again for governor in 1962. He defeated Lewis E. Lint in the Democratic primary by 48,854 votes and then defeated incumbent Governor Norman Erbe in the general election by 41,944 votes. A major issue in the 1962 campaign was the legalization of liquor-by-the-drink in Iowa, which at the time allowed only beer to be consumed over the bar, with liquor and wine limited to state liquor stores and private clubs. Hughes became a proponent of liquor-by-the-drink, and shortly after his election the state adopted a new system of alcohol control.

Hughes served as governor from 1963 until his resignation on January 1, 1969, two days before he was sworn in as a U.S. Senator. During his tenure he used his own experience as a recovering alcoholic and Christian layman to shape public policy, establishing a state treatment program for alcoholism that was intended as an alternative to commitment in state mental hospitals and aimed at reaching alcoholics “before they reach rock bottom.” He helped secure the enactment of several amendments to the Iowa Constitution, including two providing for legislative reapportionment and Iowa Supreme Court review of reapportionment, one initiating an annual session of the General Assembly, and another granting the governor a line-item veto. His administration oversaw the institution of a state scholarship program, an agricultural tax credit, the creation of a state civil rights commission, and a property tax replacement bill. He supported an educational radio-television system, improvements in workmen’s and unemployment compensation laws, additional state funding for school aid, and a consumer safeguard bill. Hughes also played a significant role in eliminating the death penalty in Iowa and personally appealed to President John F. Kennedy to commute the federal death sentence of Victor Feguer, though Kennedy declined, judging the crime too brutal.

Hughes’s political stature grew during the 1960s. At the 1964 Democratic National Convention he delivered a speech seconding the nomination of President Lyndon B. Johnson, a decision he later came to regret as he grew disillusioned with Johnson’s Vietnam policies. In his 1964 reelection campaign for governor, his Republican opponent, Evan Hultman, attacked him for not publicly acknowledging his 1954 relapse into alcoholism, questioning his integrity. Hughes responded forthrightly in a debate, declaring, “I am an alcoholic and will be until the day I die…. But with God’s help I’ll never touch a drop of alcohol again. Now, can we talk about the issues of this campaign?” The Des Moines Register reported that the audience reaction was immediate and overwhelmingly supportive, and later editorialized that anyone who had overcome such a battle deserved commendation rather than censure. Hughes went on to win in a landslide, carrying all but two of Iowa’s 99 counties. In 1966 he was renominated for governor without opposition in the Democratic primary and defeated Republican William G. Murray in the general election by 99,741 votes. During these years he undertook trade missions abroad and joined other governors on a tour of Vietnam, experiences that broadened his foreign policy perspective. He also developed a close friendship with Senator Robert F. Kennedy beginning in 1966; Kennedy encouraged him to seek a U.S. Senate seat.

Hughes’s service in Congress occurred during a significant and turbulent period in American history. In 1968, amid the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., racial unrest in Iowa, and his growing opposition to American policy in Vietnam and the leadership of the Johnson administration, Hughes emerged as a prominent antiwar Democrat. At the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, he delivered a nominating speech for antiwar presidential candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy while violent demonstrations unfolded in the streets. In the general election that year he ran for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Republican Senator Bourke Hickenlooper. Although initially considered a heavy favorite against Republican state senator David M. Stanley of Muscatine, Hughes won only narrowly and took his seat in the Senate on January 3, 1969. A member of the Democratic Party, he served one term, representing the interests of his Iowa constituents and contributing to the legislative process during a time marked by the Vietnam War, social unrest, and evolving federal policy on civil rights and social welfare.

In the Senate, Hughes quickly became a leading voice on issues of alcoholism and drug addiction, drawing on his personal history. He persuaded the chairman of the Senate Labor and Public Welfare Committee to establish a Special Subcommittee on Alcoholism and Narcotics, which he chaired. The subcommittee held public hearings on July 23–25, 1969, giving unprecedented congressional attention to alcoholism. Witnesses included prominent figures in recovery such as Academy Award–winning actress Mercedes McCambridge, National Council on Alcoholism founder Marty Mann, and Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder Bill W. Hughes later wrote that he had invited a dozen other well-known individuals in recovery to testify, but all declined. Some in the AA community viewed the hearings as a potential threat to anonymity and sobriety. Hughes also emphasized the need for treatment of drug addiction, arguing that “treatment is virtually nonexistent because addiction is not recognized as an illness.” Although these efforts initially received limited press coverage amid intense media focus on the Vietnam War, poverty, and other national crises, they contributed to major legislative developments. The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, regarded as a major milestone in national efforts to address alcohol abuse and alcoholism, aimed “to help millions of alcoholics recover and save thousands of lives on highways, reduce crime, decrease the welfare rolls, and cut down the appalling economic waste from alcoholism.” The act established the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and subsequent legislation in 1974 created the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Hughes also helped create the Society of Americans for Recovery to further public advocacy on addiction issues.

During his Senate term Hughes was occasionally mentioned as a potential national candidate. In early 1970 he began to receive press attention as a “dark horse” for the 1972 Democratic presidential nomination. Columnist David Broder described him as “a very dark horse, but the only Democrat around who excites the kind of personal enthusiasm the Kennedys used to generate.” Hughes denounced President Richard Nixon’s secret wiretapping activities, conducted through the FBI, in 1971 and was increasingly identified with reform and civil liberties causes. Yet he appeared to many observers to be a reluctant presidential contender and, in the eyes of some in the Washington press corps, too much of a “mystic,” given his open discussion of religion, drugs, and alcohol. Columnist Mary McGrory wrote that he disliked small talk and preferred serious conversation, and that he resisted the usual rituals of courting political financiers and party leaders, preferring instead to spend time visiting young people in treatment centers. His discomfort with traditional campaigning contributed to his decision to withdraw from the 1972 presidential race. Journalist Hunter S. Thompson later reported that political strategist Gary Hart suggested after the 1972 campaign that Hughes might have been the only Democrat who could have defeated Nixon. After ending his own bid, Hughes joined the presidential campaign of Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine as campaign manager. Hughes chose not to seek reelection to the Senate in 1974, concluding his congressional service in 1975.

In his personal life, Hughes’s long marriage to Eva Mercer ended in divorce in 1987. Six weeks after the divorce he married his former secretary, Julie Holm, with whom he had been living for about a year during his separation from Eva. He moved to Arizona and lived there with his second wife in a single-family home, while his first wife resided in a one-bedroom apartment in Iowa. The divorce led to bitter disputes over alimony and child support in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Eva Hughes contended that he had cut off her annuities and health insurance, while Hughes asserted that he himself lacked sufficient funds. Ultimately, a court ordered him to repay more than $10,000 to his former wife, a sum that was successfully collected from his estate after his death. Financial difficulties mounted in his later years. The Harold Hughes Center, associated with his advocacy work, experienced declining fortunes, leaving him owing approximately $80,000 to creditors in the 1990s. Combined with increasing medical expenses and court-ordered alimony payments, these obligations caused his debts to rise sharply, and he died virtually bankrupt. Harold Everett Hughes died on October 23, 1996, leaving a legacy as a transformative Iowa governor, a one-term U.S. senator, and a pioneering national advocate for the recognition and treatment of alcoholism and drug addiction.

Congressional Record