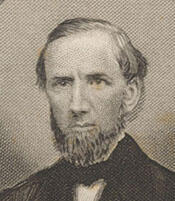

George Washington Julian (May 5, 1817 – July 7, 1899) was an American politician, lawyer, and writer from Indiana who became one of the leading antislavery and reform voices in mid‑nineteenth‑century national politics. Born near Centerville in Wayne County, Indiana, to Quaker parents who had migrated from North Carolina, he grew up in a milieu strongly opposed to slavery. His father died when Julian was young, and he worked from an early age as a schoolteacher and surveyor to help support his family. These formative experiences, along with his Quaker background, contributed to his lifelong commitment to abolition, equal rights, and land reform.

Julian studied law while teaching school and was admitted to the bar in 1840. He established a legal practice in Greenfield, Indiana, and quickly became involved in public affairs. Initially a member of the Whig Party, he served in the Indiana House of Representatives in 1845–1846, where he began to distinguish himself as an outspoken opponent of slavery and its expansion. By the late 1840s he had aligned with the Free Soil movement, which opposed the extension of slavery into the western territories. In 1847 he embraced the cause of women’s suffrage after reading Harriet Martineau’s discussion of the “political non-existence of woman” in Society in America, a position he would maintain and advocate for the rest of his life.

Julian was first elected to the United States House of Representatives as a Free Soiler from Indiana and served in the Thirty‑first Congress from March 4, 1849, to March 3, 1851. During this initial term he gained notice as a vigorous antislavery advocate. In 1852 he was nominated by the Free Soil Party as its candidate for vice president on the ticket headed by John P. Hale, a national recognition of his prominence in the movement to restrict slavery. Although the ticket was unsuccessful, the campaign further established Julian as a leading figure among radical reformers. In 1853, while campaigning in Indiana, he invited early woman suffrage advocates Frances Dana Barker Gage and Emma R. Coe to lecture in his hometown of Centerville, reflecting his growing public commitment to women’s rights.

By the mid‑1850s Julian had joined the newly formed Republican Party. In 1856 he served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where the party nominated John C. Frémont for president. Julian chaired the committee on national organization, underscoring his importance in the party’s early development. In 1860 he was elected as a Republican to the Thirty‑seventh Congress and was subsequently re‑elected to the Thirty‑eighth, Thirty‑ninth, Fortieth, and Forty‑first Congresses, serving continuously from March 4, 1861, to March 3, 1871. Across these six terms in office, representing Indiana in the House of Representatives, he became one of the most radical of the U.S. House Republicans and a prominent Radical Republican leader during the American Civil War and Reconstruction era.

Julian’s congressional service coincided with one of the most consequential periods in American history, and he used his position to advance abolition, civil rights, women’s suffrage, and land reform. Appointed to the House Committee on Public Lands in 1861, he became its chairman in 1863 and held that post until 1871. In this capacity he played an important role in securing passage of the Homestead Act of 1862, which he hailed as “a magnificent triumph of freedom and free labor over slave power.” When he later discovered that the law contained loopholes that favored land speculators, he introduced measures to close them. He was an outspoken critic of railroad land grants and opposed the Morrill Act of 1862, which provided federal land grants to establish agricultural and mechanical colleges, believing such grants improperly favored corporate and institutional interests over ordinary settlers. He also chaired the Committee on Expenditures in the Navy Department during the Thirty‑ninth Congress.

During the Civil War Julian emerged as an ardent abolitionist legislator. He called for arming Black men and enlisting them as Union soldiers and, in 1864, unsuccessfully sought repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law in the Thirty‑eighth Congress; his bill was tabled by a vote of 66 to 51, though a similar measure became law two years later. He served on the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, which, though lacking formal policy‑making authority, investigated military and civil conduct and provided a vehicle for Radical Republicans to press their views on the Lincoln administration. In that role Julian investigated Confederate atrocities and the mistreatment of prisoners of war, criticized generals he believed insufficiently aggressive, and strongly supported the removal of General George B. McClellan, whose reluctance to advance he regarded as nearly treasonable. He challenged colleagues who urged that the war be fought strictly within traditional constitutional limits, dismissing what he called “the never‑ending gabble about the sacredness of the Constitution” and denouncing the Confederates as “red‑handed murderers and thieves” who had betrayed the Union.

Julian’s radicalism extended to Reconstruction policy and the disposition of Confederate property. He supported the Second Confiscation Act of 1862 and advocated permanent confiscation of rebel estates, which he proposed to divide into free homesteads for Union soldiers, loyal citizens, and Black laborers who had aided the Union. On March 18, 1864, he introduced a House bill to establish homesteads on confiscated southern lands; it passed the House along party lines, 75 to 64, but U.S. Attorney General James Speed halted confiscations before the Senate could act. Julian initially joined efforts to replace Abraham Lincoln on the 1864 Republican ticket with Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, but he later broke with the movement and supported Lincoln’s re‑election. He opposed Lincoln’s comparatively moderate Reconstruction policies and favored the stricter provisions of the Wade–Davis Bill of 1864, while becoming a strong advocate of Black suffrage. In January 1865 he voted for the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, later recalling the vote as “the greatest event of this century” and likening the names of those who supported it to the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

In the immediate postwar years Julian urged harsh measures against leading Confederates. He publicly called for the execution of Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee and suggested that the estates of about twenty prominent Confederate leaders be confiscated and parceled out to poor whites and Blacks in the South, including Union veterans. He was among the earliest members of Congress to call for the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson and in 1867 was appointed to a seven‑member House committee charged with drafting articles of impeachment. Although he was not selected as one of the impeachment managers to prosecute the case in the Senate, he strongly supported Johnson’s removal, later characterizing the impeachment movement in his memoirs as an episode of “party madness” and downplaying his own role. Throughout this period he remained a consistent advocate of women’s enfranchisement, proposing a constitutional amendment for woman suffrage in 1868, which was defeated. He maintained close friendships with leading women’s rights activists, including Lucretia Mott, and continued to press the issue even as national attention focused on Reconstruction and Black male suffrage.

Julian’s uncompromising style and reform agenda made him a formidable but often polarizing figure in Congress and Indiana politics. Contemporary observers described him as six feet tall, broad‑shouldered, and slightly stooped, with a “worn, scarred, seamed and earnest face” of “the Round‑head, Cromwellian type.” A Philadelphia correspondent wrote in 1868 that he “towers above the people like a mountain surrounded by hills” and was “always being found in the right place, never doubtful.” Others complained that “he uses vinegar when he might scatter sugar,” noting his prickly personality and determination “to fight to the bitter end.” His long‑running feud with Indiana’s powerful Republican governor Oliver P. Morton, who was slower to embrace Black suffrage and more cautious in breaking with President Johnson, culminated in Morton’s 1867 gerrymander of Julian’s strongly antislavery district. Radical counties were replaced with more Democratic‑leaning areas, forcing Julian into a difficult re‑election fight in 1868, which he barely won amid accusations of voting fraud in Richmond, Indiana. In 1865 he had also been involved in a notorious personal altercation with his political opponent, Brigadier General Solomon Meredith, who attacked him with a whip at an Indiana train station, beating him into unconsciousness in what newspapers dubbed the “Julian and Meredith Difficulty.”

By 1869, after passage of the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteeing Black male suffrage, Julian believed the central struggle against slavery and its immediate legacies had largely been won, even as he lamented that some of the most steadfast antislavery leaders—such as Salmon P. Chase, Charles Sumner, and Horace Greeley—had been marginalized within the Republican Party they had helped to found. In 1870 he sought renomination for his House seat but faced a strong conservative challenger, Judge Jeremiah M. Wilson. Of the eleven Republican newspapers in Indiana’s Fourth District, only three supported Julian, while eight backed Wilson. Julian lost the Republican nomination and withdrew from the race. Although he endorsed the party’s eventual nominee in the general election, his support came late in the campaign and he did not actively participate, effectively ending his congressional career in March 1871 after six terms in office.

In his later years Julian remained active in public life as a writer, lecturer, and reform advocate. He continued to support land reform, civil rights, and women’s suffrage and published essays and memoirs reflecting on his long career and the evolution of the Republican Party. In 1885 President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, appointed him surveyor general of the New Mexico Territory, a post he held until 1889. The appointment by a president of the opposing party testified to Julian’s reputation for integrity and administrative competence, as well as to his national standing as a reformer. His family life also reflected his political commitments: he married into a prominent antislavery family, becoming the son‑in‑law of Ohio abolitionist congressman Joshua Reed Giddings, and his daughter, Grace Julian Clarke, became a noted women’s suffrage advocate and civic leader in Indiana.

George Washington Julian died on July 7, 1899, in Irvington, then a suburb of Indianapolis, Indiana. His remains were interred at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis. At the time of his death, obituaries described him as a “doctrinaire rather than a statesman,” but also as an “eloquent speaker,” a “forceful writer,” and a “powerful champion” of the causes he favored. Commentators emphasized both his impatience, arrogance, and self‑righteousness, and his tireless industry and steadfast adherence to principle. While he was widely known in his own day for his antislavery agitation during the Civil War and Reconstruction, his advocacy of land reform and women’s suffrage was less appreciated. In later years his legacy was commemorated locally when Indianapolis Public School Number 57 was named in his honor, reflecting enduring recognition of his role as one of Indiana’s most prominent nineteenth‑century reformers and members of Congress.

Congressional Record