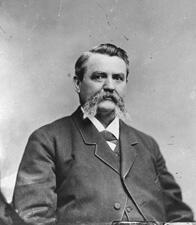

George Miles Chilcott (January 2, 1828 – March 6, 1891) was an American farmer, lawyer, and Republican politician who served as a delegate to the United States House of Representatives from the Territory of Colorado and later as a United States senator from the State of Colorado. His congressional service occurred during a significant period in American history, spanning the era of territorial organization in the West and the early years of Colorado’s statehood, and he participated in the legislative and democratic processes as a representative of his frontier constituents.

Chilcott was born near Cassville in Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania, on January 2, 1828. In 1844 he moved with his parents to Jefferson County, Iowa, then part of the rapidly developing American frontier. In Iowa he studied medicine for a short time, continuing this course of study until about 1850, but ultimately chose to adopt the life of a farmer and stock raiser. His early engagement in public affairs began in Jefferson County, where he was elected sheriff in 1853, gaining administrative and law-enforcement experience in a rural community undergoing settlement and growth.

In 1856 Chilcott moved farther west to the Territory of Nebraska. That same year he was elected a member of the Nebraska Territorial Legislature from Burt County, participating in the governance of a territory that was central to debates over westward expansion and the organization of new states. He left the Nebraska legislature in 1859 when he moved again, this time to the Territory of Colorado, following the broader migration associated with the development of the Rocky Mountain region.

In Colorado, Chilcott quickly became involved in the political and legal foundations of the new territory. He was a member of the constitutional convention and of the territorial legislature during its first two sessions, in 1861 and 1862, helping to shape the initial framework of territorial governance. During this period he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1863, establishing himself as an attorney. From 1863 to 1867 he served as register of the United States Land Office for the Colorado district, a position of importance in a region where land claims, settlement, and resource development were central to public policy and economic life.

Chilcott’s congressional career began while Colorado was still a territory. In 1865 he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a delegate from the Territory of Colorado, but was not admitted to that Congress. In 1866 he was again elected, this time successfully taking his seat as a Republican delegate to the Fortieth Congress, where he served from March 4, 1867, to March 3, 1869. As a territorial delegate he participated in debates and committee work, though without a formal vote on the House floor, and represented the interests of Colorado’s residents during a period marked by Reconstruction and continued western expansion. Later, he returned to territorial politics, serving on the Colorado Territorial council for two years between 1872 and 1874.

Following Colorado’s admission to the Union as a state in 1876, Chilcott continued his public service at the state level. He became a member of the Colorado House of Representatives in 1878, contributing to the early legislative development of the new state. On April 11, 1882, he was appointed to the United States Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Senator Henry M. Teller, who had entered the Cabinet as Secretary of the Interior. As a Republican senator in the Forty-seventh Congress, he served from April 11, 1882, until the expiration of the term in 1883. Although his tenure in the Senate lasted only about a year, he took part in the legislative process during a formative time for Colorado’s representation in the federal government. After the conclusion of this short term, he retired from public service.

In his later years, Chilcott withdrew from active political life. He died in St. Louis, Missouri, on March 6, 1891. His remains were returned to Colorado, where he was buried in Masonic Cemetery in Pueblo, reflecting his long association with the state whose territorial and early state institutions he had helped to build.

Congressional Record