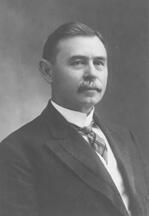

Furnifold McLendel Simmons (January 20, 1854 – April 30, 1940) was an American politician from North Carolina who served as a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives from March 4, 1887, to March 4, 1889, and as a United States senator from March 4, 1901, to March 4, 1931. Over the course of his long career, he became one of the most powerful Democratic figures in his state and in the Senate, while also emerging as a leading architect of white supremacist politics and Black disenfranchisement in North Carolina during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Simmons was born in Pollocksville, Jones County, North Carolina, the son of Mary McLendel (Jerman) Simmons and Furnifold Greene Simmons. He grew up in the post–Civil War South during Reconstruction and the turbulent years that followed, an environment that shaped his political worldview and later actions. Details of his formal education are less prominent in the historical record than his early immersion in Democratic Party politics in North Carolina, where he quickly aligned himself with conservative white interests seeking to reassert control over state government after the end of Reconstruction.

Simmons first entered national office as a Democrat in the Fiftieth Congress, representing North Carolina in the United States House of Representatives from March 4, 1887, to March 4, 1889. During this period he contributed to the legislative process as a member of the House, participating in debates and representing the interests of his constituents at a time when the South was still adjusting to the political and economic consequences of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Although he served only a single term in the House, this experience in Congress helped establish his reputation within the Democratic Party and laid the groundwork for his later prominence in state and national politics.

After Republicans and their Populist allies won control of the North Carolina legislature in 1894, Simmons emerged as a central figure in the Democratic effort to regain and consolidate power. He led an organized campaign to disenfranchise Black voters and to restore Democratic dominance across the state. Working closely with white supremacist newspapers, he promoted inflammatory rhetoric that portrayed Black men as threats to white women and as unfit for public office or the franchise. Simmons helped organize hundreds of so‑called “White Government Unions,” political clubs that openly pledged to secure Democratic control “if they had to shoot every negro in the city.” These efforts contributed directly to the Democratic sweep in the 1898 state elections and were closely intertwined with the Wilmington insurrection of 1898, a violent coup in which white supremacists overthrew the legitimately elected, biracial city government. Simmons is widely regarded as a leading perpetrator of that insurrection and as a staunch segregationist and white supremacist whose actions helped institutionalize Jim Crow in North Carolina.

In 1901, following his success in restoring Democratic control in the state, Simmons won the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate and took his seat on March 4 of that year. He would remain in the Senate for thirty years, serving six terms and becoming one of the most influential Southern Democrats in Congress. From his Senate position he built and maintained a powerful political machine in North Carolina, relying on lieutenants such as A. D. Watts, who, in the words of one journalist, “kept the machine oiled back home.” As a senator, Simmons participated actively in the legislative process during a significant period in American history that encompassed the Progressive Era, World War I, and the onset of the Great Depression, consistently representing the interests of his state and the Democratic Party’s conservative wing.

Simmons’s influence reached its peak when he served as chairman of the Senate Committee on Finance from March 4, 1913, to March 4, 1919, during the administration of President Woodrow Wilson. The Finance Committee was one of the most powerful committees in Congress, with jurisdiction over tariff, tax, and revenue legislation. In this role, Simmons helped shape major fiscal policies of the era, including measures related to the federal income tax and wartime finance during World War I. His prominence in national Democratic politics led him to seek the Democratic nomination for president in 1920, though his candidacy was unsuccessful and he did not emerge as the party’s standard-bearer.

In the late 1920s, Simmons’s standing within the national Democratic Party began to erode. In 1928 he refused to endorse Al Smith, the Democratic nominee for president and the first Catholic to be nominated by a major party. His opposition to Smith, rooted in a combination of religious, cultural, and political conservatism, won him praise from members of the Ku Klux Klan and other nativist and anti-Catholic elements. However, his public break with the party’s national ticket in 1928, combined with the political upheaval brought on by the onset of the Great Depression, weakened his position at home. In 1930 he was defeated in the Democratic primary by Josiah W. Bailey, who was backed by Governor O. Max Gardner, effectively ending Simmons’s three-decade tenure in the Senate when his term expired on March 4, 1931.

After leaving the Senate, Simmons withdrew from national public life, though he remained a figure of considerable historical and political interest in North Carolina, both for his long service in Congress and for his central role in the establishment and maintenance of white supremacist rule in the state. He died on April 30, 1940. By the time of his death, he was noted as the last U.S. senator to have served during the presidency of William McKinley, linking his career to an earlier era of American political history even as the country moved further into the modern age.

Congressional Record