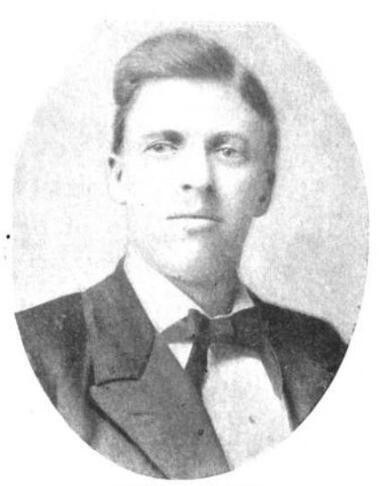

Frederick Lundin (born Fredrik Lundin Larsson; May 18, 1868 – August 20, 1947) was a U.S. Representative from Illinois and a powerful Republican Party ward boss in Chicago. He played an instrumental role in the successful mayoral elections of William Hale Thompson and in the creation of Thompson’s extensive patronage system, and he helped build up the organized political syndicate later taken over by Al Capone in 1922. His career spanned immigrant entrepreneurship, state and national legislative service, and influential—often controversial—machine politics in early twentieth-century Chicago.

Lundin was born Fredrik Lundin Larsson on May 18, 1868, in the parish of Västra Tollstad, Hästholmen, Ödeshög Municipality, Östergötland County, Sweden. He was the son of Lars Fredrik Lundin and Fredrika Larsdotter and had two sisters, Lovisa (1854–1873) and Elin. During his childhood, he immigrated with his parents and surviving sister to the United States, settling in Chicago, Illinois, in 1880. Growing up in a rapidly industrializing city with a large Scandinavian immigrant community, he completed his academic studies in Chicago before turning to business and public life.

Before entering politics, Lundin established himself as an entrepreneur in the patent medicine trade. He served as president of Lundin & Co., manufacturer of “Lundin’s Juniper Ade,” an all-purpose tonic made from juniper berry extract. The product, marketed as a remedy for a variety of ailments, reflected the era’s flourishing patent medicine industry and provided Lundin with both financial resources and name recognition. His success as a salesman and promoter earned him a reputation for organizational skill and showmanship that would later translate into political influence.

Lundin’s formal political career began at the state level. A Republican, he was elected to the Illinois State Senate, serving from 1894 to 1898. During these years he became closely associated with Chicago’s Republican organization and emerged as a protégé of William Lorimer, one of the city’s leading political figures. His growing prominence within the party led to his selection as an alternate delegate from Illinois to the Republican National Convention in 1904, underscoring his status as an important operative in state and local politics.

In 1908, Lundin advanced to national office when he was elected as a Republican to the 61st United States Congress from Illinois’s 7th congressional district, which included Chicago’s Near North Side. He served a single term in the U.S. House of Representatives from March 4, 1909, to March 3, 1911. As a member of the Republican Party representing Illinois, Lundin contributed to the legislative process during a significant period in American history, participating in the democratic process and representing the interests of his urban constituents. He was defeated for reelection in 1910 and, after leaving Congress, resumed his manufacturing interests while deepening his involvement in Chicago’s Republican machine.

Lundin’s post-congressional career was dominated by his role as a ward boss and political strategist. Richard Norton Smith later described him as “a Lorimer protege esteemed for his organizational gifts and excused for his eccentricities,” and as “fossil evidence that democracy and flim-flaming go hand in hand.” Lundin, who liked to refer to himself with contrived modesty as “the Poor Swede,” used his skills honed as a patent medicine salesman—peddling Juniper Ade—to build a disciplined political organization. In exchange for his supporters voting as he directed, he arranged jobs for them, mainly in the municipal sector, creating a loyal base that he could mobilize in citywide contests.

Lundin reached the height of his influence in municipal politics through his alliance with William Hale Thompson. He was instrumental in Thompson’s election as mayor of Chicago in 1915, orchestrating a broad coalition of voters and leveraging his ward organization on Thompson’s behalf. Once Thompson was in office, Lundin played a central role in constructing a vast patronage system. He succeeded in getting more than 30,000 of his supporters appointed to the city payroll, a form of political graft in which many appointees were required to kick back part of their pay to Lundin’s organization. This network of patronage and political protection helped foster the environment in which organized crime flourished, and Lundin’s political syndicate was later built upon and effectively taken over by Al Capone in 1922.

Lundin’s power began to wane in the early 1920s. In 1922 he was indicted on a charge of embezzling tax money, an episode that publicly highlighted the financial underpinnings of his machine. Although he was ultimately acquitted, the indictment marked the beginning of the end of his career as a political boss in Chicago. His influence within the Republican organization diminished as reform movements and rival factions challenged the old patronage structures that had sustained his power.

In his later years, Lundin withdrew from the front lines of politics. He eventually left Chicago and spent his final period in California. Frederick Lundin died in Beverly Hills, California, on August 20, 1947. His body was returned to the Chicago area, and he was interred in Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois.

Congressional Record