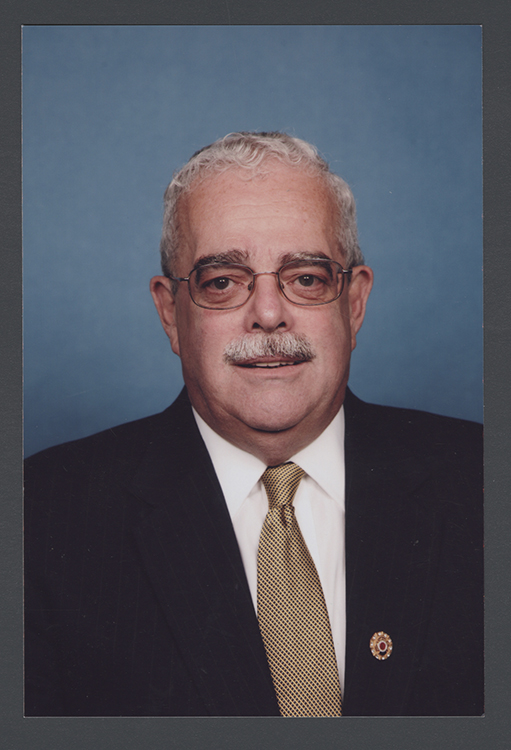

Elliott Muse Braxton (October 8, 1823 – October 2, 1891) was a nineteenth-century politician, lawyer, and slaveholding planter from Virginia. A member of the Democratic and Conservative parties, he served in the Virginia Senate, fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War, and represented Virginia for one term in the United States House of Representatives during the turbulent Reconstruction era. He was the great-grandson of Carter Braxton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and part of a prominent Tidewater family long influential in Virginia politics and plantation society.

Braxton was born on October 8, 1823, either in Mathews County or in Fredericksburg, Virginia, to Carter Moore Braxton Sr. He lost his mother in childhood, and his father later remarried; among his younger half-siblings was Carter Moore Braxton, who would become a civil engineer. The Braxton family, merchants and planters centered in King and Queen County, had been prominent in colonial and early republican Virginia. His great-great-grandfather George Braxton Sr., great-grandfather George Braxton Jr., and grandfather Carter Braxton all represented King and Queen County in the Virginia General Assembly, and the family owned large plantations worked by enslaved laborers. Elliott Braxton received a private education appropriate to his social class. His father, who guided his early legal studies, died in 1847, leaving him to complete his preparation for the bar on his own.

After reading law under his father’s supervision until the elder Carter M. Braxton’s death, Elliott M. Braxton was admitted to the bar in 1849. He began his legal practice in Richmond County, in Virginia’s Northern Neck, where his extended family remained influential. Richmond, Lancaster, Northumberland, and Westmoreland County voters elected him to the Virginia Senate in 1851 to replace Joseph Harvey in a district that, before the census and the Virginia Constitutional Convention’s redistricting, had also included Stafford and King George Counties. He served in the state senate from 1852 to 1856, and in 1853 he defeated Whig candidate John T. Rice of Westmoreland County. While in the Virginia Senate, Braxton sat on the Committee for Courts of Justice and the Joint Committee to Examine the First Auditor’s Office. He chose not to seek re-election in 1857. During this antebellum period, he was a slave owner: the 1850 census recorded him in Richmond as owning an enslaved woman, two girls aged about ten and three, and two boys about five and one year old, while the previous census had shown his late father owning twenty enslaved people in King and Queen County.

On November 23, 1854, Braxton married Anna Maria Marshall, a granddaughter of Chief Justice John Marshall, thereby linking two of Virginia’s most notable legal and political families. The couple ultimately had four daughters and four sons. By 1860, Braxton’s legal practice in the Northern Neck was not flourishing, and he moved to Fredericksburg, Virginia, where his half-brother Carter Moore Braxton was overseeing construction of the roadbed for the Fredericksburg and Gordonsville Railroad as a civil engineer. Elliott Braxton continued to practice law in Fredericksburg and lived there with his wife and their three young daughters. In the 1860 census, he appears to have leased out his remaining enslaved people, including a forty-five-year-old man in Northumberland County and a thirty-year-old man in Richmond County, reflecting both his continued participation in slavery and the shifting economic circumstances of the period.

With the secession crisis and the outbreak of the Civil War, Braxton aligned himself with the Confederacy. As Virginians voted to leave the Union, he first enlisted as a private and then raised a company in Stafford County for Confederate service. On July 18, 1861, he was elected captain of this company, which was incorporated into the 30th Virginia Infantry in September 1861. He was re-elected captain on April 16, 1862. In August 1862, Braxton was promoted to major and assigned as brigade quartermaster on the staff of Confederate General John R. Cooke. During the later stages of the war, in the autumn of 1864, he sought but did not obtain an army judicial post. His Confederate service, combined with his status as a slave owner and member of the antebellum political elite, would shape his postwar political identity and his role in Reconstruction-era debates.

After the Confederacy’s defeat, Braxton returned to Fredericksburg and resumed his legal career. He opened a law office with C. Wistar Wallace, a former comrade from the 30th Virginia Infantry. Like many former Confederates, he faced legal disabilities imposed under Reconstruction, but he succeeded in having these removed and re-entered public life. In 1866 he won election to Fredericksburg’s common council, participating in local governance as Virginia’s political order was being reshaped. The state government underwent a major reorganization in 1868 as a result of Congressional Reconstruction, and Braxton emerged as part of the Conservative movement that opposed Radical Republican policies and sought to restore the political influence of prewar elites.

Braxton’s national political career came during this contentious period. Running as a Conservative aligned with the Democratic Party, he sought election to the United States House of Representatives from Virginia’s 7th Congressional District. He defeated the Republican incumbent, Lewis McKenzie, by a margin of 53 to 47 percent. McKenzie contested the outcome, alleging voter intimidation, but the House Committee on Elections ultimately determined that Braxton had been duly elected and seated him. As a member of the Democratic Party representing Virginia, Braxton contributed to the legislative process during his single term in Congress, serving in the Forty-second Congress from March 4, 1871, to March 3, 1873. During his tenure, he was not assigned to any standing committees, but he spoke in defense of states’ rights and the Conservative Party’s positions, reflecting the broader Southern resistance to federal Reconstruction measures. He also moved unsuccessfully to secure compensation for the Lee family for the Arlington plantation, which the federal government had seized during the Civil War and converted into a national cemetery. Following redistricting, Braxton ran for Congress again, this time from Virginia’s 1st District, opposing Republican lawyer and newspaperman James B. Sener. In that closely contested race he lost by a narrow margin of 49 to 51 percent, a difference of 373 votes, ending his brief congressional career.

After leaving Congress, Braxton returned permanently to his law practice in Fredericksburg. He continued to be identified with Democratic and Conservative politics and remained a figure of local prominence, though he did not again hold high office. In the 1880s he began to suffer from heart disease, which increasingly limited his activities but did not entirely curtail his professional work. He lived out his later years in Fredericksburg, where he had established both his family and his legal reputation.

Elliott Muse Braxton died at his home in Fredericksburg on October 2, 1891, just six days short of his sixty-eighth birthday. He was interred in the Confederate Cemetery in Fredericksburg, a burial place that reflected both his service in the Confederate Army and his enduring identification with Virginia’s antebellum and Civil War–era elite.

Congressional Record