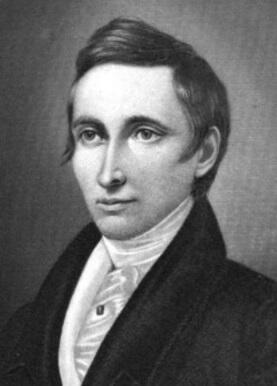

Daniel Pope Cook (1794 – October 16, 1827) was a politician, lawyer, and newspaper publisher from the U.S. state of Illinois. An anti-slavery advocate, he was the state’s first attorney general and later served three terms in the United States House of Representatives as a member of the Adams Party representing Illinois. He is the namesake of Cook County, Illinois, and his congressional service occurred during a significant period in American history, in which he participated in the democratic process and represented the interests of his constituents in the early years of Illinois statehood.

Cook was born in 1794 in Scott County, Kentucky, into an impoverished branch of the otherwise prominent Pope family of Kentucky and Virginia. Although his family lacked wealth, their connections placed him within a network of influential figures in the early West, including his uncle Nathaniel Pope, who would become a leading territorial official and later a delegate to Congress from the Illinois Territory. Cook’s early life in Kentucky was marked by fragile health, a condition that would trouble him throughout his short life, but he benefited from family ties that helped shape his political and legal career.

In 1815, Cook moved to Kaskaskia, in the Illinois Territory, then the territorial capital and a focal point of political and commercial activity on the American frontier. He initially worked as a store clerk, but soon began to read law under the supervision of his uncle Nathaniel Pope, thereby entering the legal profession through the traditional method of apprenticeship rather than formal schooling. His abilities and family connections quickly brought him to public attention. In 1816, territorial governor Ninian Edwards appointed Cook as the territorial Auditor of Public Accounts, prompting Cook to move to Edwardsville, Illinois. There he entered the world of journalism by purchasing The Illinois Herald newspaper, in partnership with Daniel Blackwell, from Matthew Duncan, and he renamed it The Western Intelligencer. Through this paper, Cook began to exert influence over public opinion in the territory.

Cook’s growing prominence coincided with the broader national politics of the Monroe administration. When Nathaniel Pope became the territorial delegate to the U.S. Congress, Cook moved to Washington, D.C., to establish his own career in the nation’s capital. In 1817 he traveled to London to deliver dispatches and to bring back John Quincy Adams, then the U.S. minister to Great Britain, whom President James Monroe had appointed secretary of state. The long voyage back to the United States allowed Cook and Adams to become closely acquainted, a relationship that would later shape Cook’s alignment with the Adams Party. Shortly after returning from England, dissatisfied with the limited role of dispatch-bearer, Cook returned to Illinois and threw himself into the movement for statehood and the struggle over slavery in the territory.

Back in Illinois, Cook used his newspaper and his new appointment as clerk to the territorial House of Representatives to advocate for admission to the Union as a free state. He became an ardent supporter of statehood and an outspoken anti-slavery advocate. Under his influence, the Territorial Legislature unanimously passed a resolution on December 10, 1817, urging statehood and explicitly forbidding slavery. Cook also lobbied his contacts in Washington and Virginia, while his uncle Nathaniel Pope conveyed the territorial resolution to the U.S. Congress on January 16, 1818. Congress responded favorably, and after both the Senate and House agreed, President Monroe signed the law on April 18, 1818, authorizing Illinois to hold a convention to adopt a state constitution and elect officers. On December 3, 1818, Monroe signed the law admitting Illinois as the twenty-first state. During this period, Cook also briefly served the Illinois Territory as judge of the western circuit, further consolidating his legal and political credentials.

Despite his central role in securing statehood, Cook’s first bid for national office was unsuccessful. After Illinois became a state, he ran for the U.S. House of Representatives but lost to John McLean by only fourteen votes for the short term remaining in the Congress. The new state legislature, however, recognized his abilities and appointed him as the first attorney general of Illinois, making him the chief legal officer of the young state. In this capacity, Cook helped establish the foundations of Illinois’s legal system while maintaining his public profile through his legal work and his ongoing engagement in political debates, particularly those involving slavery and land policy.

Cook again sought election to Congress in 1818, this time for a full term, and defeated John McLean in the general election. He was reelected in 1820 after a campaign that prominently featured the debate over slavery, and again in 1822 and 1824, thus serving three consecutive terms and becoming the second representative from Illinois, although the first to serve a full term. In Congress, Cook aligned with the Adams Party and contributed actively to the legislative process. He served on the Committee on Public Lands and later on the powerful Ways and Means Committee. From these positions he worked to shape federal policy affecting the western states and territories. Among his notable achievements was securing a grant of government lands to aid in the construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, a project that would later prove crucial to the economic development of Illinois by linking the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River system.

Cook’s anti-slavery convictions remained central to his public life. In the 1824 election cycle, he played a key role in defeating a proposed Illinois constitutional convention that would have legalized slavery in the state, helping to preserve Illinois as a free state despite strong pro-slavery pressures. At the end of that same year, when the presidential election of 1824 was thrown into the House of Representatives, Cook supported John Quincy Adams and was among those whose votes helped secure Adams’s election as president. His close relationship with Adams, dating back to their voyage from London, reinforced his identification with the Adams Party and its national program of internal improvements and economic development.

On May 6, 1821, Cook married Julia Catherine Edwards, the daughter of his mentor, Governor Ninian Edwards, who was related by marriage to the Pope family of Kentucky. The marriage further strengthened the alliance between two of the most influential political families in early Illinois. The couple had at least one son, John Cook, born in 1825. John Cook would later remain true to the family’s anti-slavery principles, becoming mayor of Springfield, Illinois, in 1855, a brigadier general in the Union Army during the Civil War, and a state representative for Sangamon County, Illinois. After Daniel Cook’s death, Julia Cook moved back to Belleville, Illinois, but she survived her husband by only three years.

By the mid-1820s, Cook’s lifelong poor health began to deteriorate further. During the 1826 congressional campaign he was unable to campaign vigorously. Although he again outpolled his old rival John McLean, he was defeated by Joseph Duncan, a pro-slavery Jacksonian Democrat, reflecting both Cook’s physical incapacity to wage a full campaign and the rising strength of Jacksonian politics in Illinois. In the spring following his defeat, President John Quincy Adams appointed Cook to a diplomatic mission to Havana, Cuba, in the hope that a change of climate might improve his condition. The mission, however, did not restore his health. Cook returned to Edwardsville and then requested to be taken back to his birthplace in Scott County, Kentucky.

Daniel Pope Cook, who had always suffered from poor health, died in Scott County, Kentucky, on October 16, 1827, at the age of thirty-two. His early death cut short a career that had already left a substantial imprint on the political and legal development of Illinois, particularly in the areas of statehood, anti-slavery policy, and internal improvements. Three years after his death, in recognition of his contributions, Cook County, Illinois, which includes the city of Chicago, was named in his honor.

Congressional Record