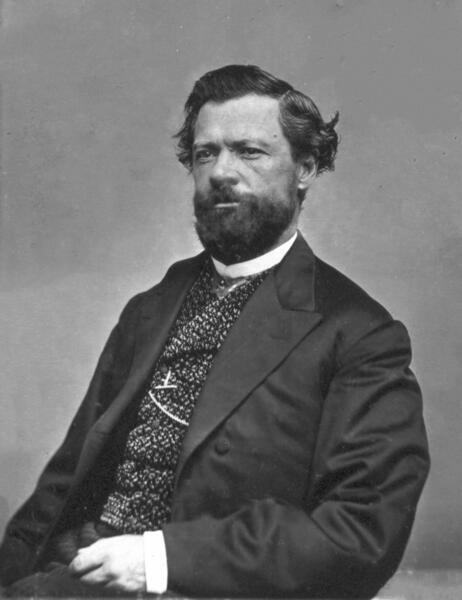

Charles Debrille Poston (April 20, 1825 – June 24, 1902) was an American explorer, prospector, author, politician, and civil servant. Widely referred to as the “Father of Arizona” for his central role in lobbying for the creation of Arizona Territory, he became the territory’s first Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives and a prominent early advocate of its mineral development and settlement. A member of the Republican Party during his congressional service, he represented Arizona Territory for one term during a critical period of the Civil War era, participating in the national legislative process and seeking to advance the interests of his constituents.

Poston was born near Elizabethtown, Hardin County, Kentucky, to Temple and Judith Debrille Poston. His father was a printer, and as a boy Poston served as a printer’s devil in his father’s shop. Orphaned at the age of twelve, he was apprenticed to Samuel Haycraft, the local county clerk, from whom he learned clerical work and the rudiments of the law. After completing his apprenticeship, he moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he clerked for the Tennessee Supreme Court while reading law. In November 1849 he married Margaret Haycraft, Samuel Haycraft’s daughter. The couple had a daughter, Sarah Lee Poston, who survived to adulthood. The 1850 census recorded Charles Poston as the owner of at least one enslaved person. On February 12, 1851, Margaret Poston became paralyzed, possibly from a stroke suffered while giving birth to a second child, and she was thereafter cared for by relatives until her death from cancer on February 26, 1884. Poston later married former newspaper typesetter Martha “Mattie” Tucker on July 27, 1885; the couple separated shortly afterward, but there is no evidence that they ever divorced.

Drawn west by the California Gold Rush, Poston traveled to California and, in February 1851, secured a clerkship at the San Francisco Customs House. He remained there until 1853, when he was demoted and complained that his replacement was a professional gambler and political appointee. While in San Francisco he became involved with a group of French bankers interested in the lands encompassed by the recently negotiated Gadsden Purchase. Backed by these investors, Poston joined mining engineer Herman Ehrenberg in organizing an exploratory expedition into the territory Mexico was expected to cede to the United States. Sailing from San Francisco in late 1853, the party was shipwrecked near Guaymas, Mexico, and briefly detained by Mexican authorities as suspected filibusters before being allowed to proceed north toward the Gadsden region. The expedition visited San Xavier del Bac and Ajo, collecting mineral samples, then traveled down the Gila River. At Fort Yuma, near the confluence of the Gila and Colorado rivers, Poston first met the post’s commander, Major Samuel P. Heintzelman. While there he surveyed a townsite on the south side of the Colorado River, a mile below the fort at Jaeger’s Ferry, which he named Colorado City and later sold for $20,000 upon his return to San Francisco.

Seeking capital to exploit the mineral prospects he had identified, Poston left San Francisco for the East Coast. After several unsuccessful attempts to raise funds, he was introduced by Heintzelman to a group of Cincinnati, Ohio, investors. On March 24, 1856, they secured US$2 million to organize the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company, with Heintzelman as president and Poston as managing supervisor. The company established its headquarters at Tubac, in what was then New Mexico Territory and later Arizona Territory, and began mining operations in the nearby Santa Rita Mountains and other locations. In Tubac, Poston served as alcalde of a settlement that grew to roughly 800 people and became popularly known as “Colonel” Poston. Exercising authority derived from the territorial government at Santa Fe, he printed his own scrip, officiated at marriages and divorces, and presided over baptisms. These activities drew the attention of church authorities, and Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy sent his vicar, Father Joseph P. Macheboeuf, from Santa Fe to investigate. After questioning the validity of the marriages Poston had performed, the vicar accepted a US$700 donation and formally sanctified the unions. During this period, Poston’s brother John was murdered by Mexican outlaws at Cerro Colorado in southern Arizona, a town Charles Poston had helped establish. The mining operations were initially successful, reportedly producing up to US$3,000 per day in silver until 1861. With the outbreak of the American Civil War and the withdrawal of Union troops from the region, Apache attacks intensified, and Tubac was eventually abandoned.

Forced to leave Tubac under the pressure of Apache hostilities, Poston went to Washington, D.C., where he worked as a civilian aide to General Heintzelman. In the capital he was introduced to President Abraham Lincoln and used his access to lobby Lincoln and members of Congress for the creation of a separate Arizona Territory. Emphasizing the region’s mineral wealth and its strategic value to the Union cause, he became one of the leading civilian advocates for territorial status. As the Arizona Organic Act neared passage, Poston attended an oyster dinner at which territorial patronage positions were informally divided among outgoing members of Congress, and he was selected to serve as an Indian agent for the new territory. To commemorate the signing of the Arizona Organic Act, he commissioned Tiffany & Co. to create a US$1,500 inkwell from Arizona silver, which he presented to President Lincoln. On March 12, 1863, he was appointed superintendent of Indian affairs for Arizona Territory, and on July 18, 1864, he was elected as the territory’s first Delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives.

As a Republican Delegate representing Arizona Territory in the Thirty-eighth Congress, Poston served from March 4, 1864, to March 3, 1865. In this nonvoting role he worked to secure recognition and support for the new territory, submitting bills aimed at settling private land claims and establishing Indian reservations along the Colorado River. His efforts reflected both his experience in frontier administration and his belief that orderly development required clear land titles and a defined federal Indian policy. During his campaign for reelection in 1865, however, Poston chose not to return to Arizona to canvass the territory, a decision that contributed to his defeat by John Noble Goodwin. A subsequent attempt to regain the delegate seat in 1866 was also unsuccessful, ending his brief congressional career.

After leaving Congress, Poston opened a law office in Washington, D.C., and continued to cultivate political and literary interests. In 1867 he traveled to Europe, spending time in London and Paris. Returning to Washington, he published a travel book, Europe in the Summer-Time, in 1868. That same year, Secretary of State William H. Seward commissioned him to carry the Burlingame Treaty to the Emperor of China and to study irrigation and immigration in Asia. Poston’s travels took him through China and then to India, where he developed a lasting fascination with the Parsi community and the ancient religion of Zoroastrianism. By early 1869 he had reached Egypt and was in Paris by April of that year. After a year in Paris he moved to London, where he spent approximately six years working as an editor for a London newspaper, serving as a foreign correspondent for the New York Tribune, and practicing as a “counselor-at-law.” During this period he produced several works, including The Parsees (1872), The Sun Worshippers of Asia (1877), and the poem Apache Land (1878). His later work Building a State in Apache Land was published in installments in the Overland Monthly between July and October 1894.

Poston returned to the United States in time to attend the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. Through his acquaintance with John Bigelow, he became a campaign worker for Democratic presidential candidate Samuel J. Tilden in the election of 1876, hoping to receive a consular appointment in London if Tilden prevailed. When that expectation was thwarted by the disputed outcome of the election, Poston instead accepted appointment as registrar of the United States land office at Florence, Arizona, a position he held from July 1877 to June 1879. While living in Florence he pursued an eccentric spiritual project inspired by his interest in Zoroastrianism: he sought to build a Parsi-style fire temple on a nearby hill. He paid for the construction of a road to the summit and erected a structure decorated with a blue and white flag bearing a red sun, built upon the ruins of an older Indigenous site. Construction ceased when he exhausted his funds, and his efforts to raise additional money—including an appeal to the Shah of Iran—were unsuccessful. The “eternal flame” he envisioned soon went out, and his unusual religious interests led some contemporaries to regard him as a crank and eccentric.

In the years that followed, Poston remained in Arizona and the Southwest, supporting himself through a variety of occupations. After leaving Florence he moved to Tucson, where he worked as a lecturer, mining and railroad promoter, and writer. In 1884 he was appointed a consular agent at Nogales, on the U.S.–Mexico border. He later served as a civilian military agent in El Paso, Texas, in 1887 and was employed by the U.S. Geological Survey in 1889. Despite his earlier prominence, he gradually declined into obscurity and financial difficulty. His situation came to wider attention in 1897 when Whitelaw Reid published an account of his circumstances, prompting renewed public interest in the aging pioneer. In response, the Arizona Territorial Legislature granted him a pension of US$25 per month in 1899, increasing it to US$35 per month in 1901.

Poston died of apparent heart failure on June 24, 1902, in Phoenix, Arizona Territory. Although he had expressed a wish to be buried on the summit of Primrose Hill near Florence, where he had attempted to build his “Temple to the Sun,” he was initially interred in a pauper’s grave in Phoenix. On the 100th anniversary of his birth, his remains were exhumed and reburied on the hill above Florence, which was renamed Poston Butte. The reinterment took place in an official ceremony led by Arizona Territorial Governor George W. P. Hunt, honoring Poston’s role as a founder and early champion of Arizona.

Congressional Record