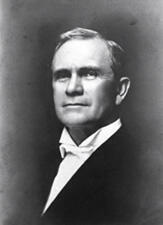

Braxton Bragg Comer (November 7, 1848 – August 15, 1927) was an American planter, industrialist, and Democratic politician who served as the 33rd governor of Alabama from 1907 to 1911 and as a United States senator from Alabama from 1920 to 1921. As governor, he presided over significant reforms in railroad regulation and business rates, and he increased funding for the public school system, contributing to the expansion of rural schools and high schools for white students and a rise in the state’s literacy rate. His later appointment to the United States Senate placed him in national office during a consequential period in American political and economic history.

Comer was born on November 7, 1848, in Spring Hill, Barbour County, Alabama, the fourth son of John Fletcher Comer and Catharine (Drewry) Comer. His parents were planters who built their wealth on enslaved labor on a large cotton plantation, and he grew up in the plantation economy of the antebellum South. Comer began his formal education at the age of ten under the tutelage of E. N. Brown. In 1864 he entered the University of Alabama, but his studies were interrupted in April 1865 when Union troops under General John T. Croxton burned the university near the end of the Civil War. He subsequently enrolled at the University of Georgia in Athens, where he joined the Phi Kappa Literary Society, and later transferred to Emory and Henry College in Virginia, from which he graduated in 1869 with both A.B. and A.M. degrees.

Following his education, Comer returned to Alabama and established himself as a planter and businessman before entering public life. He inherited the Comer family’s 30,000-acre (120 km²) plantation, devoted primarily to corn and cotton production, and became a prominent figure in the state’s agricultural economy. He also developed interests in mineral resources, including the Comer mines near Birmingham, known as the Eureka Mines, reflecting his early engagement with the region’s emerging industrial sector. As cotton prices fell and many poor white farmers lost their land, turning to sharecropping and tenancy, Comer’s enterprises operated within and benefited from the broader transformations of the post-Reconstruction Southern economy.

Comer’s most consequential business undertaking was in the textile industry. In the 1890s the Trainer family of Chester, Pennsylvania, sought to expand their textile operations into the growing industrial city of Birmingham, Alabama, and offered stock to local business leaders. Frederick Mitchell Jackson Sr., president of Birmingham’s Commercial Club, pledged substantial financial support to bring textile mills to the city as a means of providing employment in the young and struggling urban center. In 1897 the Trainers approached Comer to assume the presidency of their new enterprise. Motivated, as his son James McDonald Comer later recalled, by a belief that Birmingham needed an industry that could employ women as well as men, Comer invested $10,000 and accepted the presidency of Avondale Mills. That same year he built the first mill in Avondale, an area that would later become part of Birmingham. In its first year of operation, Avondale Mills used 4,000 bales of cotton; by 1898 it employed 436 laborers and generated $15,000 in profit. By the turn of the century, Avondale Mills had set the course for future industrial development, and by the time Comer became governor in 1907, the company had declared $55,000 in profit and produced nearly 8,000,000 yards of material. Over the next three decades, Avondale Mills, operated with the assistance of Comer’s sons, grew into one of the largest textile companies in Alabama, expanding to ten mills in seven communities and operating 282,160 spindles, including facilities such as the Eva Jane, Central, Sally B, and Catherine mills in Sylacauga; the Alexander City Cotton Mills; the Sycamore Mills; Mignon; Bevelle Mill; and the Pell City Manufacturing Company. In keeping with common industrial practices of the era, the mills employed child labor.

Comer’s prominence as a planter and industrialist led naturally into a political career within the Democratic Party, which dominated Alabama politics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He entered public life as a reform-minded businessman critical of railroad freight rates and corporate practices that he believed disadvantaged Alabama shippers and farmers. His advocacy for stronger state regulation of railroads and utilities, along with his reputation as a successful industrial leader, helped propel him to the governorship. Elected as the 33rd governor of Alabama, he served from 1907 to 1911. During his administration he championed and secured legislation to regulate railroad rates and operations, aiming to make Alabama’s business environment more competitive with other states. He also pursued tax and regulatory measures intended to strengthen the state’s fiscal position and to support infrastructure and institutional development.

A central feature of Comer’s gubernatorial tenure was his emphasis on public education for white Alabamians. He substantially increased state funding for the public school system, which led to the establishment of more rural schools and the creation of at least one high school in each county for white students. These measures contributed to a measurable rise in the state’s literacy rate and marked a significant expansion of Alabama’s educational infrastructure, though they were implemented within the segregated framework of the Jim Crow South and did not extend comparable benefits to Black citizens. Comer’s administration thus combined progressive economic and educational reforms with the racial and social limitations characteristic of Southern politics in his era.

After leaving the governorship in 1911, Comer returned to his business interests while remaining an influential figure in Alabama’s Democratic Party. His long-standing prominence in state affairs and his reputation as a reform governor positioned him for national office. He was appointed and then served as a United States senator from Alabama from 1920 to 1921, filling a vacancy and completing one term in the Senate. During this brief period in Congress, he participated in the legislative process and represented the interests of his Alabama constituents at a time when the nation was grappling with the aftermath of World War I, economic readjustment, and evolving federal regulatory policies. His Senate service, though short, capped a public career that had already reshaped aspects of Alabama’s economic and educational landscape.

In his later years, Comer continued as president of Avondale Mills, a position he had held continuously since 1897. Under his leadership the company remained a major employer and industrial presence in Alabama until his death. Comer died on August 15, 1927, while still serving as president of Avondale Mills. His legacy in Alabama is reflected in numerous institutions named in his honor, including B. B. Comer Memorial High School, B. B. Comer Memorial Elementary School, and B. B. Comer Memorial Library in Sylacauga, once home to one of Avondale’s largest mills; B. B. Comer Hall at the University of Alabama, which houses the Department of Modern Languages; the Braxton Bragg Comer Hall at Auburn University, which contains offices and laboratories for the School of Agriculture; a federal building in Birmingham; and the B. B. Comer Bridge in Scottsboro, Alabama.

Congressional Record