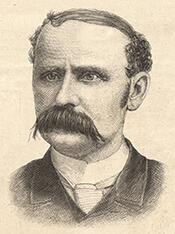

Benton McMillin (September 11, 1845 – January 8, 1933) was an American politician and diplomat who served as a Representative from Tennessee in the United States Congress from 1879 to 1899 and as the 27th governor of Tennessee from 1899 to 1903. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented Tennessee’s 4th congressional district for ten consecutive terms and later served as United States Minister to Peru from 1913 to 1919 and Minister to Guatemala from 1920 to 1921 during the administration of President Woodrow Wilson. Known as the “Democratic War Horse” for his persistent and long-running campaigning on behalf of the Democratic Party, he was a prominent figure in Tennessee and national politics for more than half a century.

McMillin was born in Monroe County, Kentucky, the son of John McMillin, a wealthy planter, and Elizabeth (Black) McMillin. He was raised in a slaveholding, pro-Southern household and, during the Civil War, supported the Confederacy. As a youth he sought to join the Confederate Army but was unable to obtain his father’s permission. At one point during the conflict he was captured by Union forces and briefly jailed for refusing to take the Oath of Allegiance. He attended Philomath Academy in Clay County, Tennessee, and later studied at Kentucky A&M (now the University of Kentucky) in Lexington, acquiring the education that would underpin his later legal and political career.

After the war, McMillin read law under Judge E. L. Gardenshire in Carthage, Tennessee, and was admitted to the bar in 1871. He began practicing law in Celina, Tennessee, and quickly entered public life. In 1874 he was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives, where he gained early experience in legislative procedure and state governance. The following year, Governor James D. Porter appointed him to negotiate a territorial purchase from Kentucky, a task that reflected his growing reputation as a capable negotiator. In 1877, after his term in the state legislature, he was appointed special judge of Tennessee’s Fifth Judicial District by Governor Porter, further enhancing his standing in state legal and political circles.

In 1878, McMillin was elected to the first of ten consecutive terms in the United States House of Representatives, defeating incumbent Haywood Y. Riddle to represent Tennessee’s 4th district. He served in Congress from March 4, 1879, to March 3, 1899, a twenty-year tenure that spanned a significant period in American history marked by Reconstruction’s aftermath, industrial expansion, and growing debates over currency, tariffs, and imperialism. As a member of the House of Representatives, McMillin participated actively in the legislative process and represented the interests of his constituents while consistently opposing what he regarded as excess government spending, protective tariffs, and many of the nation’s emerging overseas ventures, which he criticized as imperialistic. He supported antitrust legislation and currency expansion and opposed the Lodge Bill of 1890, which would have provided federal protections for Black voters in the South. Serving on the powerful House Rules Committee in the 1890s, he frequently challenged the authority of Speaker Thomas B. Reed, aligning himself with Democrats who resisted centralized control of House procedures.

McMillin’s most nationally consequential legislative initiative came in connection with the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act of 1894, to which he attached an amendment establishing a federal income tax. The measure was enacted but soon challenged in the courts, leading to the landmark Supreme Court decision in Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co. (1895), which declared the federal income tax unconstitutional. Although the decision invalidated his amendment, McMillin continued to advocate for a federal income tax, and his long campaign on the issue was ultimately vindicated with the adoption of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913, which granted the federal government explicit authority to levy income taxes. His congressional service thus linked him directly to one of the central constitutional and fiscal debates of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In 1897, McMillin sought the United States Senate seat left vacant by the death of Isham G. Harris but failed to gain sufficient support within the legislature-dominated selection process. Turning instead to the state’s chief executive office, he secured the Democratic nomination for governor in 1898 in the race to succeed the popular Governor Robert Love Taylor. In the general election he won by a large margin, receiving 105,640 votes to 72,611 for Republican candidate James Alexander Fowler, 2,428 for Populist candidate W. D. Turley, and 1,722 for Prohibition candidate R. N. Richardson. He was re-elected in 1900 despite a vigorous challenge from a reorganized Republican Party led by Congressman Walter P. Brownlow, defeating Republican nominee John E. McCall by a vote of 145,708 to 119,831.

As governor from 1899 to 1903, McMillin pursued a program that combined fiscal responsibility with progressive reforms. He signed legislation authorizing counties to establish high schools and school boards and instituted a property tax to pay for standardized school textbooks across the state, thereby promoting greater uniformity and access in public education. In 1901 he approved legislation aimed at reducing child labor by raising the state’s minimum age for employment from 12 to 14, an early step in Tennessee’s regulation of industrial working conditions. His administration also finalized Tennessee’s boundary with Virginia and created a sinking fund to reduce the state debt, reflecting his longstanding concern with public finance. After leaving office in 1903, he established an insurance business in Nashville but remained deeply involved in Democratic Party politics.

McMillin’s prominence within the Democratic Party earned him the nickname “Democratic War Horse.” He served as a presidential elector in fourteen presidential elections from 1876 to 1932 and attended nearly every Democratic National Convention during that span, missing only the 1916 election as an elector and the 1920 convention as a delegate. In 1912, amid a bitter intra-party struggle over statewide prohibition, he was again nominated by the Democrats for governor in an effort to unseat Republican Governor Ben W. Hooper. McMillin represented the “Regular Democrats,” who favored exempting the state’s largest cities from prohibition, while the “Independent Democrats,” supporting statewide prohibition, had broken away and joined Republicans in a “Fusionist” coalition. In the general election he was defeated, receiving 116,610 votes to Hooper’s 124,641. The campaign was overshadowed by personal tragedy when his only son fell gravely ill in Bristol, Tennessee, at the end of October; McMillin and his wife remained at their son’s bedside for nearly a week, canceling campaign engagements shortly before election day.

In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson appointed McMillin Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Peru. Shortly after his arrival in Lima, he helped negotiate an “Advancement of Peace” agreement that formalized and strengthened relations between the United States and Peru, reflecting the Wilson administration’s emphasis on diplomatic engagement in Latin America. He served in Peru until 1919, when he was appointed United States Minister to Guatemala. A few months after his arrival in Guatemala City, a revolt erupted against the unpopular President Manuel Estrada Cabrera. During the ensuing turmoil, Cabrera ultimately surrendered to McMillin at the American legation to avoid capture by forces loyal to Carlos Herrera. The American embassy was damaged during Herrera’s five-day bombardment of the capital, and Herrera himself was later deposed in a coup before the end of McMillin’s tenure in 1921. These episodes placed McMillin at the center of significant political upheaval in Central America and required careful navigation of U.S. diplomatic interests and local revolutionary movements.

Upon returning to Tennessee after his diplomatic service, McMillin again sought the Democratic nomination for governor in 1922. At age seventy-seven he campaigned vigorously, but his chief opponent, Clarksville farmer and public education advocate Austin Peay, enjoyed the backing of rising Memphis political boss E. H. Crump. In a closely contested primary, Peay narrowly defeated McMillin, 63,940 votes to 59,922. After this final bid for office, McMillin returned to his insurance business in Nashville, though he continued to be regarded as an elder statesman within Tennessee’s Democratic circles and remained engaged in party affairs and national elections into his late eighties.

McMillin married Marie Childress Brown, daughter of former Tennessee Governor John C. Brown, in 1886. They had one son, John Brown McMillin (1887–1912), before Marie’s death in 1887. In 1897 he married Lucille Foster, a prominent women’s suffragist and president of the Tennessee Federation of Women’s Clubs, who later served as a civil service commissioner under President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1940s. They had one daughter, Ellinor Foster McMillin Oliver (1898–1919). McMillin’s family connections extended into broader political networks; his brother Joseph taught at Montvale Academy in Celina, where one of his students was future Secretary of State Cordell Hull, who later recalled Benton McMillin as one of his early political mentors. McMillin died in Nashville on January 8, 1933, and was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery, closing a public career that had spanned from the Reconstruction era through the early years of the New Deal.

Congressional Record