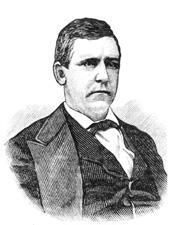

Augustus Hill Garland (June 11, 1832 – January 26, 1899) was an American lawyer and Democratic Party politician from Arkansas who rose from a prominent antebellum legal practice to become a leading figure in Confederate politics, Reconstruction-era Arkansas, the United States Senate, and the Cabinet of President Grover Cleveland. Initially an opponent of Arkansas’s secession from the United States, he ultimately served in both houses of the Congress of the Confederate States, later represented Arkansas in the United States Senate from 1877 to 1885, became the eleventh governor of Arkansas from 1874 to 1877, and served as the thirty‑eighth Attorney General of the United States from 1885 to 1889.

Garland was born in Covington, Tipton County, Tennessee, on June 11, 1832, the son of Rufus Garland and Barbara (Hill) Garland. In 1830 his father owned a store and thirteen enslaved people. When Augustus was an infant, the family moved to Lost Prairie in Lafayette County, Arkansas, along the Red River, after Rufus Garland stabbed a man in a drunken fight. Later that same year, Rufus died, and Barbara Garland and her son relocated to Spring Hill, Arkansas. In 1836 Barbara married Thomas Hubbard, a local lawyer, judge, and political candidate who, according to the 1850 census, owned five enslaved people. Hubbard’s legal and political career helped shape Garland’s early exposure to the law and public life.

Garland attended Spring Hill Male Academy from 1838 to 1843. In 1844 Hubbard moved the family to Washington, the county seat of Hempstead County, Arkansas. Seeking further education, Garland studied at St. Mary’s College in Lebanon, Kentucky, and then at St. Joseph’s College in Bardstown, Kentucky, from which he graduated in 1849. After completing his studies, he returned to Arkansas and briefly taught at the Brownstown School in Mine Creek, Sevier County. He then went back to Washington to read law under Simon Sanders, the Hempstead County clerk. On June 14, 1853, he married Sarah Virginia Sanders, with whom he had nine children, four of whom survived to adulthood.

Admitted to the bar in 1853, Garland began practicing law with his stepfather, Thomas Hubbard. In June 1856 he moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, where he entered into partnership with Ebenezer Cummins, a prominent attorney and former associate of Albert Pike. Upon Cummins’s death, Garland, then only twenty‑five, assumed control of the extensive practice and later took on William Randolph, a slightly younger lawyer who lived with the Garland family by 1860. In the 1860 census, Garland was recorded as owning three enslaved females—two aged twenty‑seven and one eleven years old—while his elder brother, Rufus Garland Jr., owned nine enslaved people in Hempstead County. Despite being a slaveholder, Garland represented the enslaved woman Abby Guy in two appeals before the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1857 and 1861, ultimately securing her freedom. By 1860 he had become one of Arkansas’s most prominent attorneys and, with the assistance of Maryland statesman Reverdy Johnson, was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of the United States.

Politically, Garland supported the Whig Party and later the American “Know Nothing” movement during the 1850s. Local Whigs urged him to run for county treasurer even before his legal career was fully established, but he declined. He nonetheless remained active in politics, speaking on behalf of Democratic candidate Edward A. Warren in the 1856 race for Arkansas’s Second Congressional District. In the 1860 presidential election, Garland served as a presidential elector for the Constitutional Union Party in the Arkansas Electoral College, casting his vote for John Bell and Edward Everett. The election of Republican Abraham Lincoln and the subsequent secession crisis placed Garland at the center of a rapidly polarizing political environment. He consistently opposed secession and advocated that Arkansas remain in the Union, even as his brother Rufus raised a Confederate infantry company, the “Hempstead Hornets,” and accepted a captain’s commission. Selected to represent Pulaski County at the 1861 Arkansas secession convention in Little Rock, Garland voiced his opposition to leaving the Union, but after President Lincoln called for 75,000 troops from Arkansas to suppress the rebellion, he shifted his position and supported secession.

Four days after the convention approved the ordinance of secession, Garland was appointed to the Provisional Confederate Congress, becoming its youngest member. He was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives in the First Confederate Congress in 1861, defeating Jilson P. Johnson, and served on the Committees on Public Lands, Commerce and Financial Independence, and the Judiciary. In 1862 he narrowly lost an election to Robert W. Johnson for a seat in the Confederate States Senate, the twelfth ballot going 46–42. Reelected to the Confederate House in 1863, he served alongside his brother Rufus. In 1864 he was appointed to the Confederate States Senate to fill the vacancy created by the death of Charles B. Mitchel, winning a close contest against Albert Pike. In the Confederate Congress, Garland supported President Jefferson Davis on most issues and worked to establish a Supreme Court of the Confederate States, though he opposed Davis’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. As Confederate defeat loomed, he returned to Arkansas in February 1865 to assist in the transition of power from exiled Confederate governor Harris Flanagin to Unionist governor Isaac Murphy, working with Union General Joseph J. Reynolds to facilitate Arkansas’s return to the Union.

After the Civil War, President Andrew Johnson pardoned Garland on July 15, 1865. However, under federal law of January 24, 1865, former Confederate officials were required to take the Ironclad Oath before resuming legal practice. Garland challenged this requirement in the landmark Supreme Court case Ex parte Garland, arguing that the oath was an unconstitutional ex post facto law and bill of attainder. On January 14, 1867, by a five‑to‑four vote, the Court agreed, allowing him and other former Confederates to resume their professions without the oath. The decision provoked strong criticism in the North but encouraged Southern conservatives who hoped to use the courts to limit Congressional Reconstruction. Arkansas legislators elected Garland to the United States Senate for a term beginning in 1867, but he was not permitted to take his seat because Arkansas had not yet been readmitted to representation in Congress, an outcome he had anticipated as “a doubtful, if not an empty offer.” While in Washington seeking recognition of his election, he worked behind the scenes to encourage the Supreme Court to hear Mississippi v. Johnson, a challenge to the Reconstruction Acts; the Court declined to intervene.

During early Reconstruction, Garland emerged as a leading conservative voice in Arkansas politics, widely regarded as a sharp legal mind who could work pragmatically with federal authorities. From 1868 to 1872 he largely withdrew from overt political activity to rebuild his law practice and personal finances, though he spoke out against the 1868 Arkansas Constitution. After its ratification, he and other Democrats decided to take the required “voter’s oath” and contest Republican power at the ballot box. In 1869 he helped found the Southern Historical Society and collected documents from Arkansas Confederate veterans. He also partnered in practice for several years with Sterling R. Cockrill, who later became chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court. The litigation and travel associated with Ex parte Garland left him with substantial debts, which he worked diligently to repay. By 1872, as divisions within the Arkansas Republican Party created new political openings, Democrats courted Garland as a potential candidate for the legislature and for the United States Senate. He declined to seek the governorship that year, citing the low salary and his desire to avoid what he considered “fruitless” political engagements while his financial situation remained precarious.

Garland returned to the political forefront during the Brooks–Baxter War of 1874, a violent dispute over the governorship between rival Republican claimants Joseph Brooks and Elisha Baxter. Although both men were Republicans, Baxter was more sympathetic to the Redeemers, the coalition of Democrats and former Confederates seeking to end Radical Republican control. Garland served as a primary strategist for Baxter and acted as deputy secretary of state. After Baxter was forcibly removed from the Old State House on April 15, 1874, he and his allies, including U. M. Rose, Henry C. Caldwell, and Freeman W. Compton, went to Garland’s home at 1404 Scott Street around midnight to plan their response. The next day Baxter declared martial law in Pulaski County and called on supporters to rally. As president of the Little Rock Bar, Garland organized a resolution by prominent attorneys condemning Judge John Whytock’s order that had elevated Brooks to the governorship. Garland then took up residence at the Anthony House hotel for several weeks to coordinate Baxter’s legal and political strategy. His plan to appeal directly to President Ulysses S. Grant for a special session of the now‑Democratic Arkansas General Assembly succeeded; Grant endorsed the legislature’s role in resolving the dispute, and Garland read the president’s proclamation to a large crowd in front of the Anthony House. The settlement restored Baxter to office, led to a state constitutional convention, and effectively ended Reconstruction in Arkansas, returning the state to Democratic control.

Following the drafting of a new state constitution, Arkansas voters were asked in October 1874 to ratify the document and elect a new slate of state officers. At the Democratic state convention that began on September 8, 1874, Elisha Baxter twice refused the gubernatorial nomination. Delegates then unanimously nominated Garland, after other “favorite son” candidacies were withdrawn. Republicans, protesting what they considered an illegal election, refused to nominate candidates and appealed to Congress to uphold the 1868 constitution. On October 13, 1874, voters ratified the new constitution and elected Garland as the eleventh governor of Arkansas, with near‑unanimous support. His administration faced serious challenges, including lingering turmoil from Reconstruction, the presence of violent organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, an ongoing congressional investigation into the Brooks–Baxter conflict, and a state debt of approximately $17 million. Working with the state finance board, Garland substantially reduced the debt within two years. He strongly supported public education, urging the legislature to improve schools and championing institutions for the blind and deaf. He successfully advocated for the appointment of a new president for Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas) and supported the establishment of Branch Normal College (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff), expanding educational opportunities for African Americans. His administration also created the Arkansas Bureau of Statistics and the Arkansas Bureau of Agriculture, Mining and Manufacturing, reflecting his interest in economic development and data‑driven policymaking.

In 1876 Garland ran successfully for the United States Senate as a Democrat, succeeding Republican Senator Powell Clayton. He formally took his seat in 1877 and was reelected in 1883, serving in the Senate from 1877 to 1885 during a critical period of post‑Reconstruction adjustment and economic change. As a senator from Arkansas, he participated actively in the legislative process and represented the interests of his constituents over two terms in office. He served on the Committees on Public Lands, the Territories, and the Judiciary, and was chairman of the Committee on Territories in the Forty‑sixth Congress. In these roles, he worked on issues including tariff reform, internal improvements, and the regulation of interstate commerce. He also supported the development of a federal prison system, advocated federal aid to education, and backed civil service reform, aligning himself with broader national efforts to modernize government administration and reduce patronage.

Garland resigned from the Senate in 1885 after President Grover Cleveland appointed him Attorney General of the United States, making him the first Arkansan to hold a Cabinet post. As the thirty‑eighth Attorney General, he oversaw the Department of Justice during Cleveland’s first administration. Early in his tenure he became embroiled in the Pan‑Electric Telephone Company scandal. While serving in the Senate, Garland had acquired stock in and acted as attorney for Pan‑Electric, a company organized to establish regional telephone systems using equipment developed by J. Harris Rogers. When the Bell Telephone Company sued Pan‑Electric for patent infringement, alleging that its technology closely resembled Bell’s, pressure mounted on the Justice Department to file a suit in the name of the United States to invalidate Bell’s patents and break its monopoly. Garland, now Attorney General, refused to bring such a suit, citing his conflict of interest. However, while he was on vacation, Solicitor General John Goode authorized the filing. The resulting year‑long congressional investigation and intense public scrutiny hampered Garland’s work and damaged his reputation, although President Cleveland continued to support him. In 1886 Garland also became the first, and to date the only, Cabinet secretary formally censured by Congress, after he failed to provide requested documents concerning the dismissal of a United States Attorney.

After leaving the Cabinet at the close of Cleveland’s first term in 1889, Garland returned to private law practice, drawing on his long experience before state and federal courts. He remained a respected figure in legal and Democratic Party circles, though he never again held public office. On January 26, 1899, while arguing a case before the Supreme Court of the United States in Washington, D.C., he collapsed and died at the age of sixty‑six. His career, spanning service in the Confederate Congress, the governorship of Arkansas, the United States Senate, and the office of Attorney General, reflected both the complexities of Southern politics in the nineteenth century and the broader national struggles over Union, Reconstruction, and reform.

Congressional Record