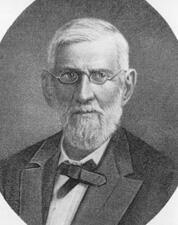

Alexandre Mouton (November 19, 1804 – February 12, 1885) was a Cajun planter, lawyer, and Democratic politician who became the first Democratic Governor of Louisiana and served as a United States Senator from Louisiana from 1837 to 1843. A prominent figure in antebellum and Civil War–era Louisiana, he held a succession of influential offices at the state and national levels and played a central role in reshaping Louisiana’s constitution and in leading the state out of the Union in 1861.

Mouton was born in the Attakapas district, in what is now Lafayette Parish, Louisiana, to Marie Marthe Bordat and Jean Mouton, both descendants of Acadian exiles. His father, Jean Mouton, founded the town of Vermilionville, which later became the city of Lafayette. Raised in a French-speaking, Catholic, and agrarian community, Alexandre Mouton attended local schools before pursuing higher education at Georgetown College in Washington, D.C. He subsequently studied law under Charles Antoine and Edward Simon in St. Martinville, Louisiana. After completing his legal studies, he was admitted to the bar in 1835 and began practicing law in Lafayette Parish. In addition to his legal work, he became a founder of the Union Bank of Louisiana and developed substantial agricultural interests, owning the 2,100‑acre Île Copal sugar cane plantation in Lafayette, which was worked by approximately 120 enslaved people.

Mouton’s personal life was closely intertwined with prominent Louisiana families. In 1826 he married Zelia Rousseau, the granddaughter of former Louisiana Governor Jacques Dupré. The couple had five children before her death in 1837, though one of the children died in infancy. In 1842 he married Emma Kitchell Gardner; this second marriage produced eight children, six of whom survived to adulthood. Through these family connections, Mouton was linked to several notable Confederate figures: his son Alfred Mouton later became a Confederate general and was killed at the Battle of Mansfield, and one of his daughters married Confederate Major General Franklin Gardner, whose older sister was Mouton’s second wife, Emma.

Mouton entered public life at a relatively young age. He was elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives in 1827 and quickly rose to prominence, serving as Speaker of the House from 1831 to 1832. A committed Democrat, he was a presidential elector on the Democratic ticket in the presidential elections of 1828, 1832, and 1836. He sought national office as a candidate for the Twenty-second Congress in 1830 but was unsuccessful. In 1836 he again served in the Louisiana House of Representatives, but he resigned the following year when he was chosen to fill a vacancy in the United States Senate created by the resignation of Senator Alexander Porter due to ill health.

As a member of the Democratic Party, Alexander Mouton was elected to the United States Senate to complete Porter’s unexpired term and was subsequently re-elected, serving from January 12, 1837, until his resignation on March 1, 1842. His tenure in the Senate thus extended over one full term, from 1837 to 1843, during a significant period in American history marked by economic upheaval and sectional tensions. While in the Senate, he served as chairman of the Committee on Agriculture, where he contributed to the legislative process on matters affecting the nation’s agrarian economy. Throughout his service, he participated in the democratic process and represented the interests of his Louisiana constituents in the upper chamber of Congress.

Mouton left the Senate in 1842 to seek the governorship of Louisiana. In the 1842 gubernatorial election he won as the Democratic candidate, becoming the first member of the Democratic Party to serve as Governor of Louisiana. He held the office from 1843 to 1846. As governor, he pursued a fiscally conservative program aimed at restoring the state’s financial stability. He reduced expenditures and liquidated state assets to balance the budget and meet bond obligations without raising taxes. Among other measures, he ordered the sale of state-owned steamboats, equipment, and enslaved laborers that had been used to remove the Red River Raft in 1834 under Governor André B. Roman. He opposed state expenditures for internal improvements, preferring to limit the role of government in such projects, and he leased out state penitentiary labor and equipment as a revenue-generating measure. Mouton strongly supported a call for a constitutional convention, the removal of property qualifications for suffrage and for holding public office, and the election of all local officials and most judges, reflecting his alignment with Jacksonian democratic principles.

Mouton’s influence extended beyond his gubernatorial term into the broader constitutional and political development of Louisiana. He played a leading role in the 1845 state constitutional convention, serving as its presiding officer and guiding the adoption of provisions that abolished property qualifications to vote or hold public office, thereby broadening political participation among white male citizens. His leadership at the convention helped reshape the state’s political framework in line with the more egalitarian tenets of the Democratic Party of his era.

With the secession crisis of 1860–1861, Mouton again emerged as a central figure in Louisiana politics. In 1861 he served as president of the Louisiana Secession Convention, where he presided over the deliberations that led to the state’s withdrawal from the Union. Under his leadership, the convention declared Louisiana a “free, sovereign, and independent power” before the state formally joined the Confederate States of America two months later. He was an active supporter of the Confederacy, devoting a large portion of his wealth to the Confederate cause. He also remained engaged in regional economic affairs, serving as president of the Southwestern Railroad Convention, and he was an unsuccessful candidate for election to the Confederate Senate.

In his later years, Mouton continued to reside in the Lafayette area, maintaining his plantation interests and local prominence even as the South underwent Reconstruction and profound social and economic change. He died near Vermilionville (now Lafayette), Louisiana, on February 12, 1885. Alexandre Mouton was interred in the cemetery at St. John’s Cathedral in Lafayette, leaving a legacy as a key Democratic leader in Louisiana’s antebellum, secession, and Civil War history.

Congressional Record