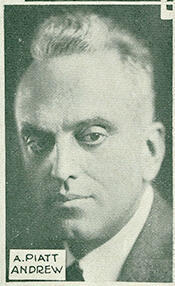

Abram Piatt Andrew Jr. (February 12, 1873 – June 3, 1936) was an American economist, public official, and Republican politician who served as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, founded and directed the American Ambulance Field Service during World War I, and represented Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives from 1921 until his death in 1936. Over eight consecutive terms in Congress, he contributed to the legislative process during a significant period in American history and represented the interests of his Massachusetts constituents.

Andrew was born in La Porte, Indiana, on February 12, 1873. He attended local public schools before enrolling at the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey. He graduated from Princeton College in 1893, and that same year entered the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. At Harvard he earned a master’s degree in 1895 and completed a doctorate in economics in 1900. He subsequently pursued postgraduate studies at the universities of Halle and Berlin in Germany and at the University of Paris, further deepening his expertise in monetary economics and international finance.

Following his graduate studies, Andrew moved to Gloucester, Massachusetts, which would remain his principal home for the rest of his life. He joined the faculty of Harvard University in 1900 as an instructor in economics and later became an assistant professor, serving there until 1909. In January 1907 he published a paper that anticipated the financial panic that struck later that year, drawing national attention to his analytical abilities. On the strength of this work and his academic reputation, he was selected to serve on the National Monetary Commission, created to study and recommend reforms to the American banking and monetary system. Taking leave from Harvard, he spent two years examining the central banks of Germany, Britain, and France.

Andrew’s government service expanded rapidly in the years that followed. He served as Director of the United States Mint in 1909 and 1910, and as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury from 1910 to 1912. In that capacity he attended the historic 1910 meeting at Jekyll Island, Georgia, with National Monetary Commission chairman Nelson W. Aldrich and leading financiers Henry P. Davison, Benjamin Strong, Paul Warburg, and Frank A. Vanderlip, where key ideas that would shape the Federal Reserve System were discussed. After the Republicans lost the White House in 1912, Andrew left office but continued to influence monetary reform. He worked informally with Democratic Senator Robert Latham Owen in drafting Owen’s version of a Federal Reserve bill, which came closest among competing proposals to the Federal Reserve Act enacted in December 1913.

Despite American neutrality at the outbreak of World War I, Andrew went to France in the summer of 1914, compelled, as he wrote to his parents, by the possibility of having “even an infinitesimal part in one of the greatest events in all history” and by “the chance of doing the little all that one can for France.” He initially drove an ambulance in the Dunkirk sector, but his energy and organizational skill were quickly recognized by Robert Bacon at the American Military Hospital, who created for him the position of Inspector General of the American Ambulance Field Service. In this role Andrew toured ambulance sections in northern France and discovered that American volunteers were frustrated by rear-area “jitney work” transporting wounded from railheads to hospitals, far behind the front, at a time when French policy barred foreign nationals from entering battle zones.

In March 1915 Andrew met with Captain Aimé Doumenc, head of the French Army Automobile Service, to argue that American volunteers wished “to pick up the wounded from the front lines…, to look danger squarely in the face; in a word, to mingle with the soldiers of France and to share their fate.” Doumenc agreed to a trial front-line unit, Section Z, whose success led the French Army by April 15, 1915, to authorize the American Ambulance Field Service, operating under French command. Andrew headed the organization—soon known simply as the American Field Service—throughout the war. When the United States Army took over its ambulance sections in late summer 1917, his role shifted to building a domestic organization based in Boston to recruit American drivers and raise funds from private donors. The Boston office was headed by his Gloucester neighbor Henry Davis Sleeper, assisted by John Hays Hammond Jr. and former driver Leslie Buswell, while the French headquarters was established at 21 rue Raynouard in Paris. By the time of militarization, the American Field Service had formed thirty-four ambulance sections with 1,200 American volunteers (2,100 in total over two years) and fourteen camion sections with 800 volunteers hauling supplies and troops along routes such as the Voie Sacrée from Bar-le-Duc to Verdun. Its motto, “Tous et tout pour France” (“Everyone and everything for France”), reflected the spirit Andrew later recalled as “glimpses of human nature shorn of self, exalted by love of country, singing and jesting in the midst of hardships, smiling at pain, unmindful even of death.”

For his wartime service, Andrew received numerous decorations from allied governments. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre and named him a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 1917; he was later promoted to officer in the Legion of Honor in 1927. Belgium recognized him as an Officer of the Order of Leopold. He also received the Army Distinguished Service Medal from the United States for his leadership of the American Field Service and his contributions to the Allied war effort.

Andrew entered elective office in the postwar period. A member of the Republican Party, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts to the Sixty-seventh Congress in a special election to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Willfred W. Lufkin. He took his seat on September 27, 1921, and was reelected to the Sixty-eighth and six succeeding Congresses, serving continuously until his death in 1936. His congressional career thus spanned eight terms during a transformative era that included the Roaring Twenties and the early years of the Great Depression. In Congress he participated actively in the legislative process and represented the interests of his Massachusetts constituents. He was a delegate to the Republican National Conventions in 1924 and 1928 and in 1924 proposed a bonus for World War I veterans, reflecting his ongoing concern for former servicemembers.

In addition to his legislative duties, Andrew remained engaged in educational and civic affairs. He served as a member of the board of trustees of Princeton University from 1932 to 1936, maintaining close ties to his alma mater and contributing to its governance during a period of institutional growth and change. His personal life was centered in Gloucester, where he lived at his home “Red Roof” on Eastern Point. A lifelong bachelor, he maintained a close relationship with his neighbor, interior designer Henry Davis Sleeper; contemporaries and later commentators have suggested that this relationship may have been romantic as well as social and professional.

Abram Piatt Andrew died at his home “Red Roof” in Gloucester, Massachusetts, on June 3, 1936, after suffering from influenza for several weeks. At 2:55 p.m. the following day, the United States House of Representatives adjourned in his honor, marking the death in office of a long-serving member. His remains were cremated, and his ashes were scattered from an airplane flying over his estate on Eastern Point in Gloucester. In 1953, in recognition of his public service as a congressman and his prominence in the community, the bridge carrying Massachusetts Route 128 over the Annisquam River to the island section of Gloucester was named the “A. Piatt Andrew Bridge” in his memory.

Congressional Record